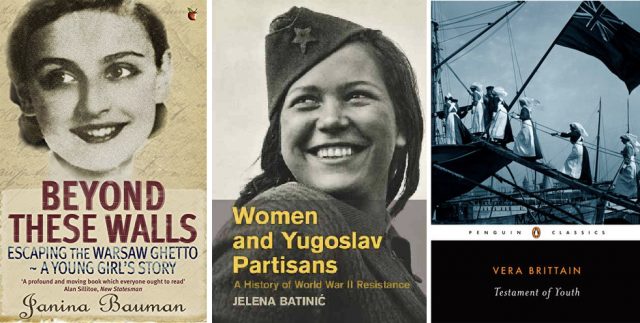

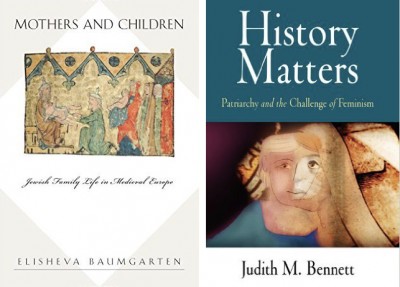

Not Even Past asked the UT Austin History faculty to recommend great books on women and gender for Women’s History Month. The response was overwhelming so we will be posting their suggestions throughout the month.

A number of people suggested books about crossing borders: about people traveling or emigrating to countries foreign to them or about people creating new hybrid identities in the places they lived. Since they don’t fit into our usual geographical categories –and raise interesting questions about those categories — we are lumping them together here in Crossing Borders.

Madeline Hsu recommends:

Emma Teng, Eurasian: Mixed Identities in the United States, China, and Hong Kong (2013)

Teng traces mixed race Chinese-white families in a number of societies and political and social circumstances to complicate presumptions about racial hierarchies and the porosity of racial border-keeping in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. By tracking mobilities through north America, Shanghai, and Hong Kong, Teng demonstrates that intermarriages occurred at higher rates than previously acknowledged, and that intermarriage with Chinese could be vehicles for upward, and not just downward, mobility depending on local circumstances.

Sam Vong recommends:

Lynn Fujiwara, Mothers without Citizenship: Asian Immigrant Families and the Consequences of Welfare Reform (2008)

Fujiwara’s study uncovers the detrimental effects that welfare reform in the 1990s had on immigrant women, particularly President Clinton’s authorization of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act in 1996 that aimed to end welfare programs. This book offers a trenchant analysis of the ways welfare reform policies redefined immigrants as outsiders and how immigrant women resisted these attempts at denying their claims to U.S. citizenship and belonging.

Michael Stoff recommends:

Susan Glenn, Daughters of the Shetl: Life and Labor in the Immigrant Generation

I’ve used this book in classes and like it a great deal. Here’s a blurb from Cornell University Press:

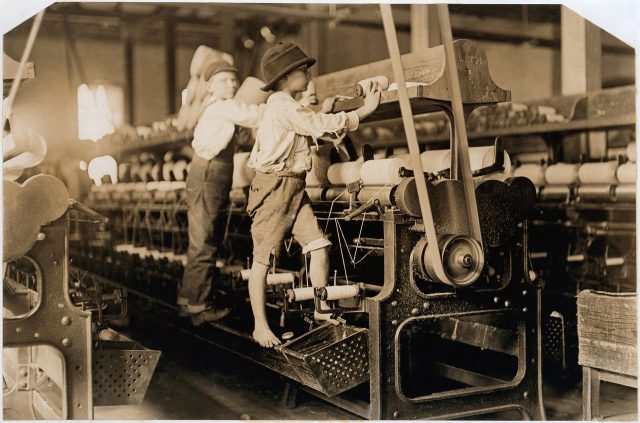

“In this fascinating portrait of Jewish immigrant wage earners, Susan A. Glenn weaves together several strands of social history to show the emergence of an ethnic version of what early twentieth-century Americans called the “New Womanhood.” She maintains that during an era when Americans perceived women as temporary workers interested ultimately in marriage and motherhood, these young Jewish women turned the garment industry upside down with a wave of militant strikes and shop-floor activism and helped build the two major clothing workers’ unions.”

Jeremi Suri recommends:

Mary Louise Roberts, What Soldiers Do: Sex and the American GI in World War II France (2014).

This deeply researched book artfully examines the interaction of race, sex, and gender in the conduct of American soldiers stationed in France and their interactions with French civilians during World War II.

Lina del Castillo recommends:

Magical sites: Women Travelers in 19th century Latin America, edited by Marjorie Agonsin and Julie Levison

This collection brings together several travel narratives written by women brave enough (and wealthy and educated enough) to travel through different parts of Latin America. Some of these writers, like Mary Caldecott Graham and Flora Tristan, found a measure of liberation from a feminine imperial mindset that justified their prescriptions for reform of the societies they encountered. Others, like Nancy Gardner Prince (a free born African American woman who traveled to Jamaica and Russia) tell their experiences from very different perspectives. The narratives these women wrote about the places they moved through show them as women who both threw off the chains of domesticity and convention and nevertheless, were in many ways still bound by them.

For more books on Women’s History:

Indrani Chatterjee, On Women and Nation in India

Our 2013 list of recommendations: New Books on Women’s History