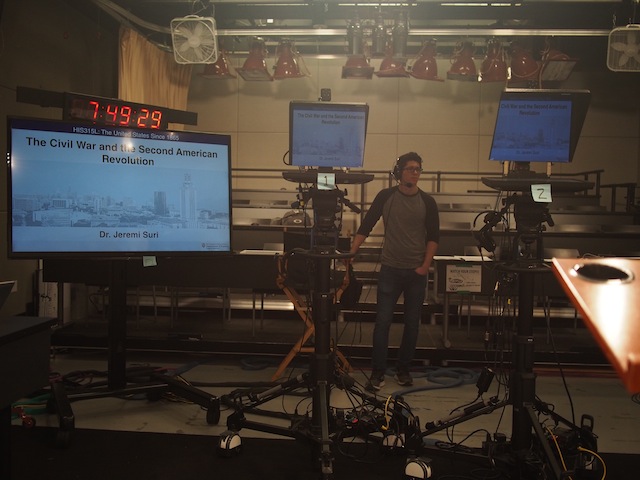

Every year thousands of students take introductory courses in U.S. History at UT Austin. This spring Prof Jeremi Suri is experimenting with an online version of the U.S. History since 1865 survey course. He and his teaching assistants, Cali Slair, Carl Forsberg, Shery Chanis, and Emily Whalen will blog about the experience of digital teaching for readers of Not Even Past.

We hold office hours every week, but how do we get more students to come? One answer might be to do it virtually.

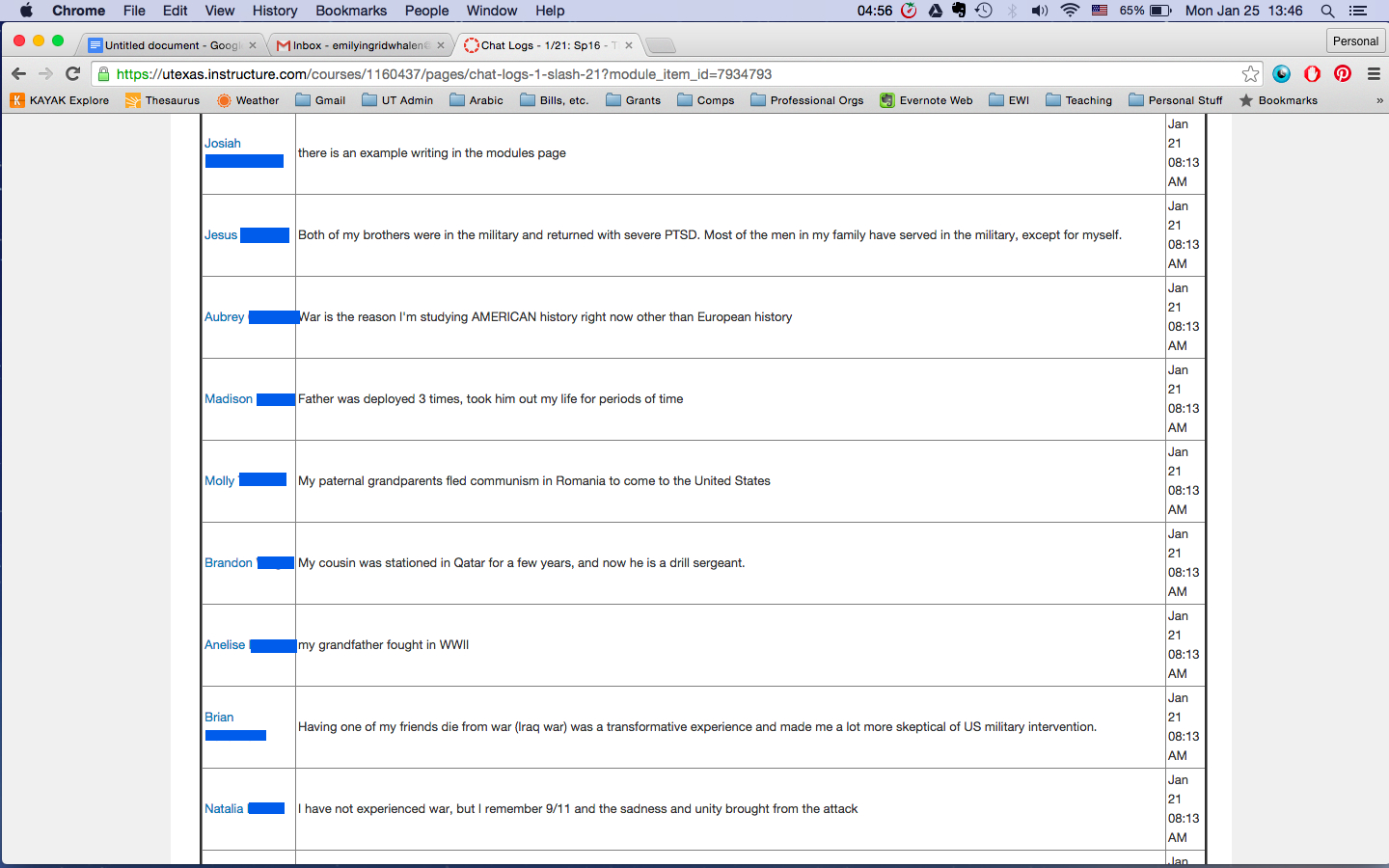

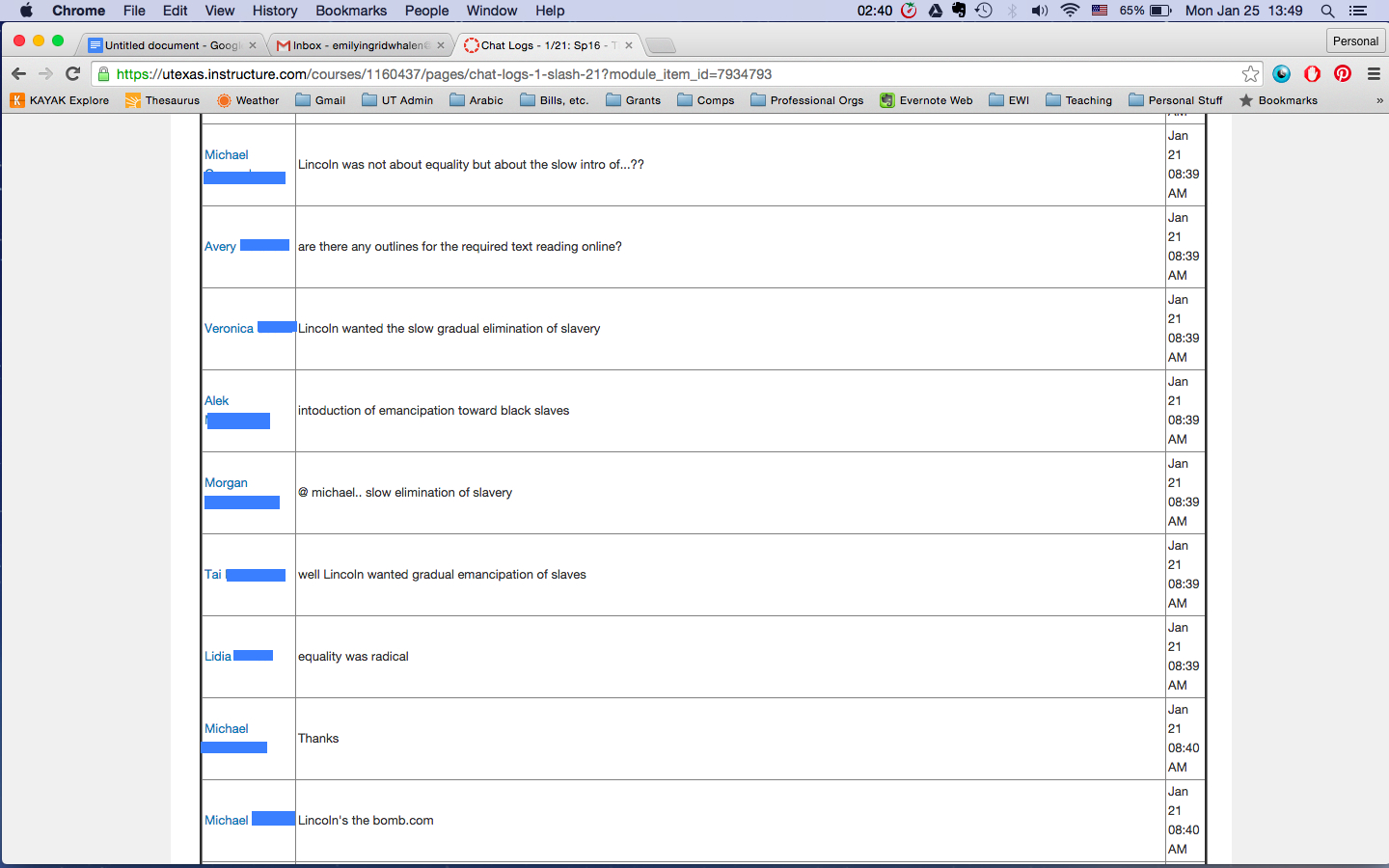

In previous blog posts, Emily and Carl have discussed how we use online tools including Class Chat, Ask the Professor, and Pings to increase student interaction and participation, and to enhance their learning experience. This design extends outside of our class time, too. Our main goal for online office hours is to make office hours more accessible and convenient for our students, so more of them can come to get detailed feedback on their weekly writing assignments or ask questions about the course.

With this in mind, one of the most exciting features of our online office hours is the flexible scheduling. We hold office hours at different times every week to accommodate the schedules of as many students as possible. We post our office hours for the coming week on Sundays, so students can plan ahead. Of course, we are also available for appointments outside of office hours.

There are two primary advantages to having office hours online. First, they can be anywhere. Just as students can live stream lectures wherever they may be, they can log on to office hours without interrupting what they have been doing. My students have logged on from their apartments or dorm rooms, as well as different parts of campus. This makes going to office hours much more convenient, and for some, less intimidating. Students who might not be as comfortable going to their TAs’ offices for one-on-one conversations right away in the beginning of the semester can take advantage of the online format to make initial contact with their TAs and build professional relationships from there. Second, we can have office hours almost anytime, not only during the day, but also in the evening. So far, I have met with students as early as 9 o’clock in the morning and as late as 9 o’clock in the evening. Four weeks into the semester, the flexible scheduling has allowed me to meet with more than a quarter of my students during office hours and through appointments.

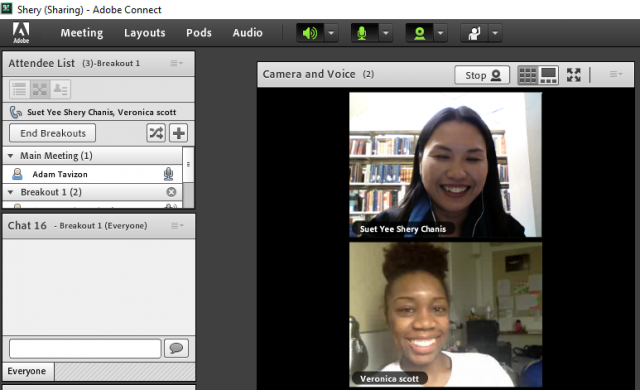

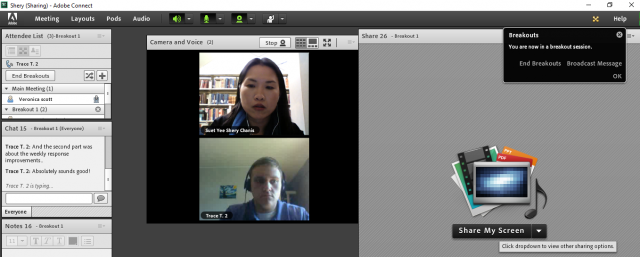

Adobe Connect is the multi-media platform we use to hold office hours. Much like social media with video chat functionalities such as Skype, Adobe Connect enables us to see students face to face and have conversations with them. I can also share my screen to go over their writing assignments in detail. After the students have logged on, they are placed in a general meeting room. Unlike the hallway outside of the office, students can sit comfortably where they are while they wait. We ask students to sign in with their arrival times, so we can meet with them in the order they arrive. To meet with a student one-on-one, we move the student and ourselves from the meeting room to a breakout session to discuss their work in private. Once we are finished with one breakout session, we place another student in a new breakout session.

Like other technology, Adobe Connect requires training and some practice. While it was straightforward to learn the tool before the semester began, in practice I have had to go through a learning curve. As I was getting ready to meet with my students for the first time, I had a few technical difficulties. Unfortunately, I had to ask the students to wait for a little while, but thankfully, my students were extremely patient and gracious!

Me: Hi everyone, unfortunately, I’m still having a bit of technical difficulty. Do you think you can log back in in about 5 minutes?

Student 1:Yes that is fine! No worries.

Me: Thanks, so much!

Student 2:Yes no problem!.

On the other side of the screen, some students have also had technical issues about getting their camera or audio to work. I have had to meet with some of them without seeing their faces or hearing their voices, but we have also been able to supplement our conversation with the chat feature and the students did not seem to mind this at all.

Through online office hours, I have also gotten to see a different side of my students. The biggest lesson I have learned so far is that students are very flexible with technology, (even though some might say they are not good at it!). They are equally comfortable with chat, video chat, or conversation. They are also quite funny at times! For one of the appointments, my student and I used the chat feature to discuss his writing assignment as we were both in quiet study areas. While he could see me, I could not see him because his camera was not working. As we were signing off at the end of our conversation, I waved goodbye through my camera, and he got creative by writing his goodbye!

Me: You are welcome! My office hours are mainly online, but like Prof. Suri said this morning, we can meet in person as well.

Student: oh ok. I’ll remember that for future reference. Thanks again! I have to get ready for my next class now.

Me: Ok, have a great rest of the day! See you soon!

Student: thanks! you too!

Student:(waves bye)

This is the first time I have held office hours online. It has been different from what I am accustomed to, but it has been a great experience and the flexible nature of online office hours has allowed me to see more students than usual. I am looking forward to getting to know my students more and getting to know more of them as the semester progresses.