“The Cause Of Her Grief”: The Rape Of A Slave In Early New England

[Trigger Warning: as the title suggests, this post contains discussion of rape]

“The Cause of Her Grief” is an article by Wendy Anne Warren that was published in the March 2007 issue of The Journal of American History.

In 1638, John Josselyn, a traveler to New England recorded a report of a slave woman just outside of Boston who was raped by a fellow slave at the behest of their owner. Warren’s article attempts to recreate the world of this enslaved woman, who arrived in the Massachusetts Bay colony on the very first ship that brought slaves there.

There are many reasons to like this article but more than anything else Warren’s honesty in trying to tell this story is poignant and powerful. Much of the article consists of questions. Warren is open about the gaps in our knowledge when it comes to topics like this. At the end she says, “At some point every historian decides how to frame her argument: I deliberately chose a method that makes visible gaps in my evidence.” This is unusual for historians, who typically try to highlight the ways they fill historical gaps and seek to persuade the reader that their interpretations are persuasive and airtight.

Warren acknowledges that we will never be able to reconstruct the rape through available historical sources. Instead, in the section where she wants to describe the rape itself, she writes:

“How did the attack occur? When? Where? Did Samuel Maverick [the slave owner] watch? Why didn’t he do it [rape her] himself? Did his skin crawl at the thought of racial mixing? Or at the thought of fathering children fated to be slaves? Did Amias Maverick [Samuel’s wife] refuse to allow another woman’s blood to stain her marriage bed? Did the Maverick daughters know what was happening? Were they being raised by the woman now being attacked? Everyone in that house knew her name, a luxury we do not share. Did any of them question what was happening?”

As a historian of slavery, this framework was breathtaking for me. At first I was uncomfortable with it. Is this history, asking unanswerable questions?

But it made me think of discussions at last year’s conference on Sexuality & Slavery: Exposing the History of Enslaved People in the Americas at the Institute for Historical Studies at UT Austin (where I am currently a PhD candidate in the History Department). To be honest, this might have been said at a panel I attended at the Berkshire Conference of Women’s Historians, which featured some of the same main people at the IHS conference. I want to give credit to whomever said these things but I can’t remember specifically who it was (though I want to say it was Barbara Krauthamer).

Anyhow, while I can’t remember precisely who said it, I remember what they said: even if we can’t answer the questions, we need to be asking them; the way you change the juggernaut of a historical paradigm is simply to ask questions that are outside of the comfortable and known. I do remember Leslie Harris saying at the Berkshire conference that she no longer allows her students to avoid answering historical questions by saying, “It’s not in the archive” because often (though, of course, not always) the answer is somewhere in the archive, just no one has looked because no one ever bothered to ask the question in the first place.

Wendy Warren asks questions. And no, probably many will never ever be answerable no matter how hard one digs in the archive. But there is worth in simply asking.

This asking of questions goes hand in hand with the…I struggle with the best word to use here…political decision Warren made to tell this story. She is upfront about it in the article:

“One story of one rape opens a view into a larger world of Anglican-Puritan rivalries, of gritty colonial aspirations, of settlement and conquest in the early modern Atlantic world, of race and sexuality and how those two constructs combined to determine the shape of many lives. But there are more compelling and human reasons to tell this story. This woman’s life deserves to be reconstructed simply because too many factors have conspired to make that reconstruction nearly impossible. Brought against her will to a foreign continent populated by peoples speaking unfamiliar languages, sold as property, raped, and then ignored in the public record, her story mirrors that of millions. Still, her individual resistance touches me; violated but not beaten, she ‘in her own Countrey language and tune sang very loud and shrill’ to a passing stranger and thus ensured her life would be remembered.”

It’s not often that reading historical scholarship makes me cry. I’ll admit, even now re-reading this passage and typing it out onto my computer screen, there’s a sheen across my eyes as I hold back tears. We need to tell the stories of people that history has conspired to silence. I take those words and hold them close to my heart.

But it wasn’t even that passage that made me want to write this post today. It is actually how Warren ends the entire piece that inspired me.

“Without imagination, how can we tell such stories? We are not scientists; we cannot test our hypotheses; we cannot recall our subjects to life and ask them to verify our claims or to provide more information on the topics they fail to discuss. We make our way among flawed sources, overreliant on written texts, hopelessly entangled in our own biases and beliefs, doing the best we can with blurry evidence, sometimes forced to speculate despite our specialized knowledge. The very beauty of history lies in that messiness, the fact that [as Hayden White put it]“unless two versions of the same set of events can be imagined, there is no reason for the historian to take upon himself the authority of giving the true account of what really happened.”

I don’t know anything about the woman who ended up on Noddle’s Island in 1638 -indeed, I suppose it is possible that Josselyn made up the story for reasons we cannot fathom, or that he misunderstood the situation, or that I have misunderstood the situation myself. But I have chosen to believe Josselyn’s version. Someone else, infuriated by my methods, can tell a different story; I embrace that possibility. In the meantime, I offer this: We have known, for a long time, a story of New England’s settlement in which ‘Mr Mavericks Negro woman’ does not appear; here is one in which she does.”

[Picture me standing up, doing a slow clap for Dr. Warren]

Warren’s brutal honesty of what it is historians do (ALL historians, whether they acknowledge the messiness of their practice or not) is, simply, wonderful.

What Warren describes here is what I imagine myself doing in my own work. It is what I strive to do: to embrace the messiness of the process, the incomplete nature of the task, the fact that we are grasping at edges and painting pictures that will forever be fragmentary – this is history. And when we choose to view the field and our work this way, it allows us to open it up to include work like Warren’s piece where gaps are openly acknowledged but in which we re-learn for the better a story that we thought we already knew. We stretch the field and bring more players onto it. We can then tell the stories of the people whose existence has been washed away by the violence of the creation of the archive without having to always answer for how unfinished those stories are.

History, as Warren says, is not science. History is messy work. And that is okay.

Because today I read about an enslaved woman in 1638 New England, about whom I would otherwise have never known.

This essay was revised for posting on Not Even Past. You can find the original on Jessica Luther’s tumblr, here.

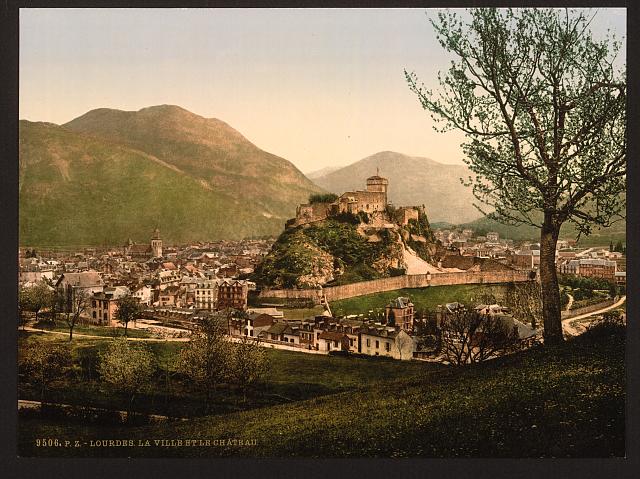

The Spanish Pyrenees, 2009 (Image courtesy of User Miguel303xm/Wikimedia Commons)

The Spanish Pyrenees, 2009 (Image courtesy of User Miguel303xm/Wikimedia Commons) The French Pyrenees, 2010 (Image courtesy of Nicolas guionnet/Wikimedia Commons)

The French Pyrenees, 2010 (Image courtesy of Nicolas guionnet/Wikimedia Commons)

His extravagant writing style and excellent use of symbolism provide several haunting and powerful images that sum up the horrors of the war like few accounts have. As one of the more famous Italian cultural figures, Malaparte was connected to the elites of Axis Europe, including aristocrats, diplomats, and Nazi leaders. This is an insider’s account that comes from a man who had a long, troublesome history with fascism. Malaparte’s description of total moral collapse is so powerful because he participated in it personally.

His extravagant writing style and excellent use of symbolism provide several haunting and powerful images that sum up the horrors of the war like few accounts have. As one of the more famous Italian cultural figures, Malaparte was connected to the elites of Axis Europe, including aristocrats, diplomats, and Nazi leaders. This is an insider’s account that comes from a man who had a long, troublesome history with fascism. Malaparte’s description of total moral collapse is so powerful because he participated in it personally. A German officer eats “C-rations” in Saarbrücken, Germany, 1945 (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

A German officer eats “C-rations” in Saarbrücken, Germany, 1945 (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)  Paris after bombardment, April 21, 1944 (Image courtesy of German Federal Archives/Wikimedia Commons)

Paris after bombardment, April 21, 1944 (Image courtesy of German Federal Archives/Wikimedia Commons) Ruins along the Pegnitz River, Germany, April 20, 1940 (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Ruins along the Pegnitz River, Germany, April 20, 1940 (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)