by Yana Skorobogatov

“Through Labor – Freedom!” read a sign above the entrance to Solovetsky, just one of the 476 camps that comprised the Soviet gulag system. This prison network – what Alexander Solzhenitsyn famously termed “the gulag archipelago” – is the subject of Gulag: A History, Anne Applebaum’s excellent Pulitzer Prize winning book. It is an impressive compendium of firsthand accounts taken from countless memoirs, archives, and oral histories conducted by both Applebaum and the organization Memorial, which was founded in 1987 to preserve the memory of those who died in the gulag. Written in a journalist’s engaging style with a historian’s attention to detail, Gulag offers readers unprecedented access to the inner workings of the Soviet prison labor camp system and the lives of the people who survived it.

This prison network – what Alexander Solzhenitsyn famously termed “the gulag archipelago” – is the subject of Gulag: A History, Anne Applebaum’s excellent Pulitzer Prize winning book. It is an impressive compendium of firsthand accounts taken from countless memoirs, archives, and oral histories conducted by both Applebaum and the organization Memorial, which was founded in 1987 to preserve the memory of those who died in the gulag. Written in a journalist’s engaging style with a historian’s attention to detail, Gulag offers readers unprecedented access to the inner workings of the Soviet prison labor camp system and the lives of the people who survived it.

Applebaum is wise to structure her book thematically in order to maximize her reader’s immersion into each facet of gulag life. Chapters devoted to the individual characters one would encounter in a gulag camp – corrupt guards, tattoo artists, women and children – animate otherwise gruesome descriptions of the processes – arrest, transport, labor, and punishment – that gulag inhabitants were forced to undergo. Several nuanced discussions of the complex power structures formed inside the gulag zona will surprise even those readers familiar with Stalinist terror. For example, a camp boss’ order that identifies the prison brigadier as “the most significant person on the construction site,” shows how the system’s industrial imperatives presented average prisoners with opportunities for upward mobility. Other details, like one man’s account of his terminally ill wife being pushed to the floor by a prison guard, underscore the brutality upon which the gulag regime was founded.

The author supplements her detailed narrative with refreshing insight on the origins of Stalinist terror, a topic that has inspired heavy debate among Soviet historians. She joins the likes of J. Arch Getty, James Harris, and Michael Jakobson to argue that the gulags were a product of on the spot improvisation rather than a premeditated master plan. In the early 1930s, the Soviet leadership in general, and Stalin in particular, constantly changed course. Neither the OGPU nor the secret police made clear their ultimate goals about the future of the gulag system. It became common, for example, for the OGPU to labor over the issue of overcrowding in prison camps and declare amnesties for prisoners as a solution, only to issue another wave of repression and new plans for camp construction shortly thereafter. Cycles like these indicate that despite Stalin’s political, economic, and even personal investment in the gulag system, its origins were haphazard and the policies that shaped it inconsistent.

Readers will notice Applebaum’s penchant for infusing her own moral insight into her narrative, a tactic that will appeal to her non-academic audience but may disquiet a few historians. She portrays the novelist Maxim Gorky as morally corrupt and opportunistic, someone who made a career out of serving the Soviet regime by praising gulag prisons (“it is excellent,” he wrote of the Solovetsky camp) and convict labor projects like the White Sea Canal. Jean-Paul Sartre is criticized for supporting Stalinism throughout the postwar years, while Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill are condemned for smiling in photographs taken with Stalin during the Yalta Conference. Applebaum expresses disdain for most leftist intellectuals and politicians who excuse Stalin’s crimes and denounce Hitler’s in a single breath. The issue of unintended consequences makes it difficult to identify and condemn immorality in retrospect, which is why most academic historians tend to keep their moral judgments at bay when writing histories of even the most reprehensible of regimes. That Applebaum – a journalist by profession – chose to stray from the facts in her introduction and closing chapters betrays an otherwise impeccable book, whose subject – the history and legacy of Stalinist injustice – is capable of commanding a reader’s moral compass all on its own.

You may also like:

UT Professor Joan Neuberger’s review of the 1964 Soviet film “I Am Twenty”

This review of Bert Patenaude’s Trotsky: Downfall of a Revolutionary

UT Professor Charters Wynn’s DISCOVER piece on Stalin’s notorious Order 227

Posted on January 16, 2012

Kamensky argues that early settlers were uniquely preoccupied with the act of speech and held to specific but unwritten rules about correct speaking. Speech was bound up with

Kamensky argues that early settlers were uniquely preoccupied with the act of speech and held to specific but unwritten rules about correct speaking. Speech was bound up with

The book, by Uruguayan author Eduardo Galeano, follows the history of Latin America and the Caribbean through a perilous centuries-long struggle against poverty and those imperial powers whose unabashed exploitation ensure its steady existence. For Galeano, Latin America is poor precisely because it is so rich.

The book, by Uruguayan author Eduardo Galeano, follows the history of Latin America and the Caribbean through a perilous centuries-long struggle against poverty and those imperial powers whose unabashed exploitation ensure its steady existence. For Galeano, Latin America is poor precisely because it is so rich.

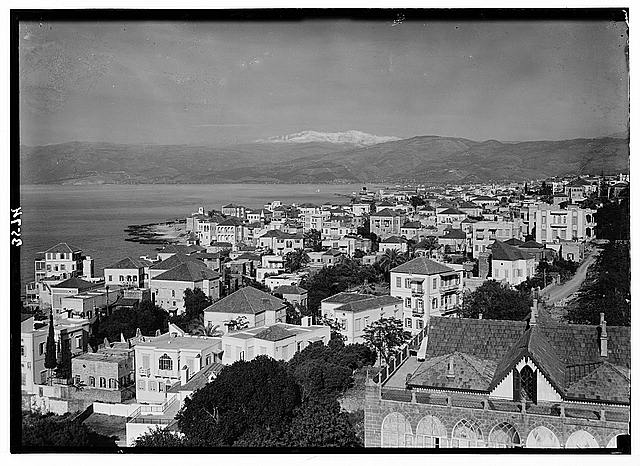

News programs the world over broadcast it into the homes of millions of people from 1975 till the Lebanese Parliament ratified the Taif accord in late 1989. Less well known is the reconstruction process that began in the Lebanese capital almost immediately after the war ended and which continues today. After commissioning but failing to implement an initial plan in 1992, the Lebanese government entrusted the reconstruction to Société libanaise pour le développement et la reconstruction de Beyrouth (Solidere), which was founded by then-Prime Minister Rafic Hariri, in 1994. Focusing primarily on the downtown area, the company sought to preserve what few buildings remained, create an international business district, and make a profit. As is the case with many urban reconstruction projects, Solidere’s plan was met with resistance and protest, especially considering the still-divided nature of Lebanese society. Therefore, Solidere took on the secondary task of defining and emphasizing an architectural heritage that could bridge the sectarian gaps inherent to Lebanon and thus Beirut.

News programs the world over broadcast it into the homes of millions of people from 1975 till the Lebanese Parliament ratified the Taif accord in late 1989. Less well known is the reconstruction process that began in the Lebanese capital almost immediately after the war ended and which continues today. After commissioning but failing to implement an initial plan in 1992, the Lebanese government entrusted the reconstruction to Société libanaise pour le développement et la reconstruction de Beyrouth (Solidere), which was founded by then-Prime Minister Rafic Hariri, in 1994. Focusing primarily on the downtown area, the company sought to preserve what few buildings remained, create an international business district, and make a profit. As is the case with many urban reconstruction projects, Solidere’s plan was met with resistance and protest, especially considering the still-divided nature of Lebanese society. Therefore, Solidere took on the secondary task of defining and emphasizing an architectural heritage that could bridge the sectarian gaps inherent to Lebanon and thus Beirut.

The book is Orwell’s personal narrative of his time spent fighting in trenches and behind barricades while slowly gaining an understanding of the politics that lay beneath the conflict. The book is not only a fascinating glimpse into a unique epoch but a fine example of Orwell’s writing style and personal life. Orwell, after all, has become a historical figure.

The book is Orwell’s personal narrative of his time spent fighting in trenches and behind barricades while slowly gaining an understanding of the politics that lay beneath the conflict. The book is not only a fascinating glimpse into a unique epoch but a fine example of Orwell’s writing style and personal life. Orwell, after all, has become a historical figure.