by Carson Stones

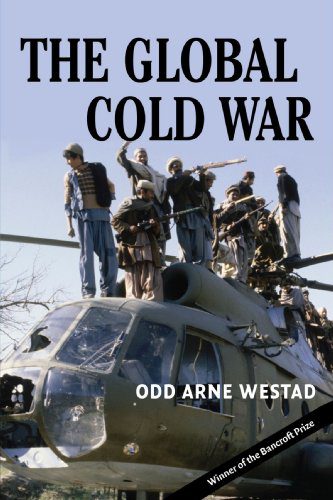

The Global Cold War by Odd Arne Westad is a fascinating account of superpower interventions in the Third World during the latter half of the twentieth century. Covering a wide sweep of history, Westad argues that the United States and the Soviet Union were driven to intervene in the Third World by the ideologies inherent in their politics.

Covering a wide sweep of history, Westad argues that the United States and the Soviet Union were driven to intervene in the Third World by the ideologies inherent in their politics.

Westad opens his book with an examination of the ideologies of the United States, the Soviet Union, and the post-colonial leaders before the Second World War. Emerging victorious from the war, Westad argues that the two countries believed it was their destiny to combat the competing ideas of modernity in the post-war era of decolonization. With the world divided between NATO and the Warsaw Pact, any country declaring independence outside the blocs was a potential battleground for the competing ideologies. In a conflict that lasted over forty years and affected billions of people worldwide, Westad highlights the events chronologically from the Korean Peninsula to Latin America, Southeast Asia, Africa, and finally the Middle East and Afghanistan.

Seamlessly tying together seemingly unrelated incidents, The Global Cold War manages to take a bird’s eye view of history while still providing incredible details of the specific events, which turned the tide of the Cold War. Westad explains that each pivotal turn represented a new ideological shift for Moscow and Washington in the continuing struggle to win the hearts and minds of newly emerging countries. A few notable incidents from the book include the CIA operations in Guatemala, containment in Vietnam, and détente in Ethiopia. As this book proves, these superpower interventions only exacerbated the conflicts of diverse nationalities who were struggling to emerge from under the heels of Imperialism. The unfortunate result of these interventions was incredible bloodshed, environmental devastation, and millions displaced as refugees. The turning point of the book is the 1979 Iranian Revolution, preaching a new ideology, Islamism, which rejected both liberal capitalism and Marxist-Leninist socialism. The best chapters in the book follow the emergence of Islamism and the repercussions of its rapid spread in a two-bloc world.

This book provided a refreshing perspective on the Cold War as it related to the political and social developments in the Third World. Echoing Clausewitz, Westad calls the Cold War “a continuation of colonialism through slightly different means.” Anyone who reads this book will appreciate Westad’s tragically ironic statement that while both Moscow and Washington were formally opposed to colonialism, the “methods they used in imposing their vision of modernity on Third World countries were very similar to those of the European Empires who had gone before them.” This book will force readers to question the motives of American foreign policies which authorized assassinations, toppled democratically elected regimes, and supported dictatorships all in the name of protecting freedom and democracy from the evils of socialism around the globe.The conclusion of The Global Cold War is especially poignant when considering the ongoing conflict in the Middle East and the return of American troops this Christmas. Twenty years have passed since the collapse of the Soviet Union but the specter of the Cold War still haunts American foreign policy today. With the breakdown of the bipolar world, this book should encourage citizens around the world to question the motives of any country, which imposes an ideology upon their neighbors as humankind progresses into the twenty-first century.

Photo credits

Unknown photographer, Soldiers ride aboard a Soviet BMD airborne combat vehicle, Kabul, 25 March, 1986

DOD Media via Wikipedia

Check out the other winning and honorable mentions submissions for our First Annual Undergraduate Writing Contest:

William Wilson’s review of George Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia

Lynn Romero’s review of Open Veins of Latin America

Katherine Maddox’s review of Beirut City Center Recovery

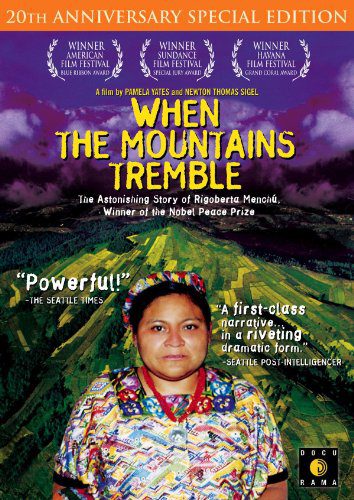

Guatemala. Denese and her adopted family travel to Guatemala, where she discovers she is Dominga Sic Ruiz, a survivor from a 1982 Guatemalan massacre in which both her parents were murdered by the Guatemalan military. The documentary recounts how Denese rediscovers her own identity as Dominga—an Achí Maya woman, and the horrendous political context that led to her being put up for adoption in the United States.

Guatemala. Denese and her adopted family travel to Guatemala, where she discovers she is Dominga Sic Ruiz, a survivor from a 1982 Guatemalan massacre in which both her parents were murdered by the Guatemalan military. The documentary recounts how Denese rediscovers her own identity as Dominga—an Achí Maya woman, and the horrendous political context that led to her being put up for adoption in the United States.

The Catholic Church at that time was under attack for its considerable wealth and social control. The unnamed priest at the center of the novel is a complicated man, by no means a conventional hero, but his refusal to abandon the priesthood eventually endows him with a magnetic aura of spirituality, despite his many vices.

The Catholic Church at that time was under attack for its considerable wealth and social control. The unnamed priest at the center of the novel is a complicated man, by no means a conventional hero, but his refusal to abandon the priesthood eventually endows him with a magnetic aura of spirituality, despite his many vices.

The novel begins in 1752, in Liverpool, England. The Royal African Company, a chartered corporation created in the mid-17th-century with a monopoly on trade with the African coast, has just lost the last of its privileges, making the slave trade, for the first time, a “free trade” (all irony intended). Inspired by the promise of lucrative profits, a Liverpool merchant, William Kemp, commissions the construction of a ship to engage in the newly opened trade. Before the ship sets sail, Kemp engages his nephew, Matthew Paris, a disgraced apothecary, to serve as the ship’s surgeon.

The novel begins in 1752, in Liverpool, England. The Royal African Company, a chartered corporation created in the mid-17th-century with a monopoly on trade with the African coast, has just lost the last of its privileges, making the slave trade, for the first time, a “free trade” (all irony intended). Inspired by the promise of lucrative profits, a Liverpool merchant, William Kemp, commissions the construction of a ship to engage in the newly opened trade. Before the ship sets sail, Kemp engages his nephew, Matthew Paris, a disgraced apothecary, to serve as the ship’s surgeon.

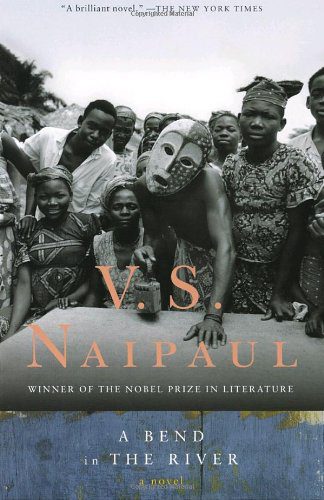

Much like its eponymous waterway, V.S. Naipaul’s A Bend in the River meanders steadily through the dark reality of postcolonial Africa, alternately depicting minimalist beauty and frightening tension. Like Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, subtle prose reveals the timelessness of the continent’s remote corners alongside human corruptibility. Yet, Naipaul moves his narrative closer in time to contemporary Africa, demonstrating that the horrifying legacies of colonialism did not end with Europe’s retreat. In A Bend in the River, the struggle to establish national identities in the wake of Western imperialism takes center stage, with “black men assuming the lies of white men” in order to govern.

Much like its eponymous waterway, V.S. Naipaul’s A Bend in the River meanders steadily through the dark reality of postcolonial Africa, alternately depicting minimalist beauty and frightening tension. Like Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, subtle prose reveals the timelessness of the continent’s remote corners alongside human corruptibility. Yet, Naipaul moves his narrative closer in time to contemporary Africa, demonstrating that the horrifying legacies of colonialism did not end with Europe’s retreat. In A Bend in the River, the struggle to establish national identities in the wake of Western imperialism takes center stage, with “black men assuming the lies of white men” in order to govern.