Islam has a long tradition in Africa dating back to the seventh century. Today, Islam plays a crucial role in the political, socio-cultural, religious, and economic lives of the population.  The inhuman event of the 9/11 attacks and the upsurge in terrorism in the world have forced western countries, especially, the United States, to re-examine their relationship with Africa. Securing Africa: Post-9/11 Discourses on Terrorism, scholars from Africa, Canada, and the US contribute cogent discourses on the significance of Africa to the US. They especially emphasize the ways that Africa is represented in public discussions of political violence and terrorism. The authors address the impact of 9/11 on Africa, and how 9/11 has informed American policies and attitudes towards Africa.

The inhuman event of the 9/11 attacks and the upsurge in terrorism in the world have forced western countries, especially, the United States, to re-examine their relationship with Africa. Securing Africa: Post-9/11 Discourses on Terrorism, scholars from Africa, Canada, and the US contribute cogent discourses on the significance of Africa to the US. They especially emphasize the ways that Africa is represented in public discussions of political violence and terrorism. The authors address the impact of 9/11 on Africa, and how 9/11 has informed American policies and attitudes towards Africa.

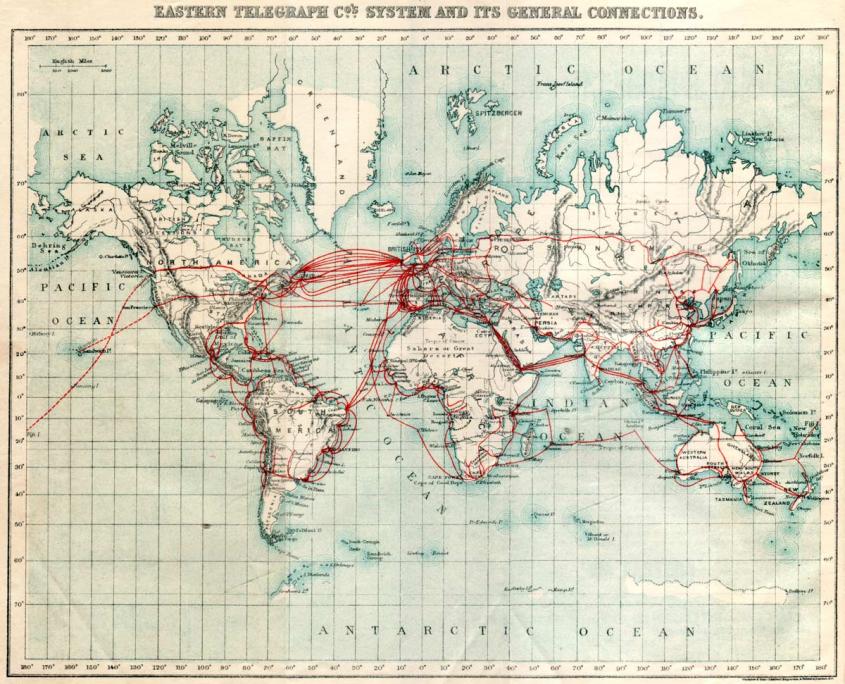

Securing Africa begins with Malinda S. Smith’s examination of the historical context in which terrorism can be placed. She claims that 9/11 gave impetus to scholars, politicians, and civil society to view terrorism as an attack on ‘civilization’ by ‘evil men’ and she engages readers on the ironies of this construct. She cautions against wholesale labeling of peoples as terrorists. She draws instances from the past such as Africans fighting colonization and the African National Congress fighting apartheid, which in her rationalization, were legitimate means of securing freedom, though labelled by the West as acts of terrorism. She analyzes how violent attacks on US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania (1998), and flight bombings in Libya, Spain, and India were not treated with the same urgency as terrorist attacks.

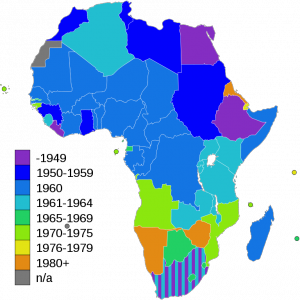

A timeline of African decolonization. Many African anti-imperial groups were initially labelled as ‘terrorists’ in the West.

A timeline of African decolonization. Many African anti-imperial groups were initially labelled as ‘terrorists’ in the West.

This opens discussions in “Part I: 9/11, Terrorism and the Geopolitics of the African Spaces,” that examine the role of intellectuals in questioning political authority, the place of Islam in Africa, and the impact of post 9/11 American rhetoric and policies on Africa. These chapters present the extent of the US war on terror on the African continent, especially in East Africa and the Sahel region. They also show that Africans’ inability to perceive European machinations perpetually leave them in a position “Part II: Africa in Post 9/11 International Relations” deals with the Cold War paradigms of relationships between democracies and containment, America’s interest in the oil reserves of the Gulf of Guinea and how oil factors into US security measures, and how the US foreign policy is linked with its economic interests in Kenya and Somalia.

The authors employ a rich selection of books, newspaper articles, and online materials to discuss such controversial issues such as Africa’s position in the war on terror, the significance of Africa to America’s security, and America’s foreign policies towards Africa. Cross-cultural and territorial comparisons enable readers to understand the authors’ points. The multi-disciplinary approach used by these contributors situates their arguments in specific contexts and reduces abstractions, bringing the issues at stake to non-specialist readers.

The US recognizes Africa as an important arena in its bid to win its war on terror but more importantly, African intellectuals also recognize that the US fight against terrorism has ideological, socio-economic, and political implications for Africans. This book is an important addition to the literature on terrorism. I recommend it for everyone interested in Africa.

Further reading:

Publisher information on Securing Africa, with an extract from the book.

A short essay from the Metropolitan Museum of Art on the spread of Islam into Africa.

The Atlantic Monthly on terrorism in Uganda.

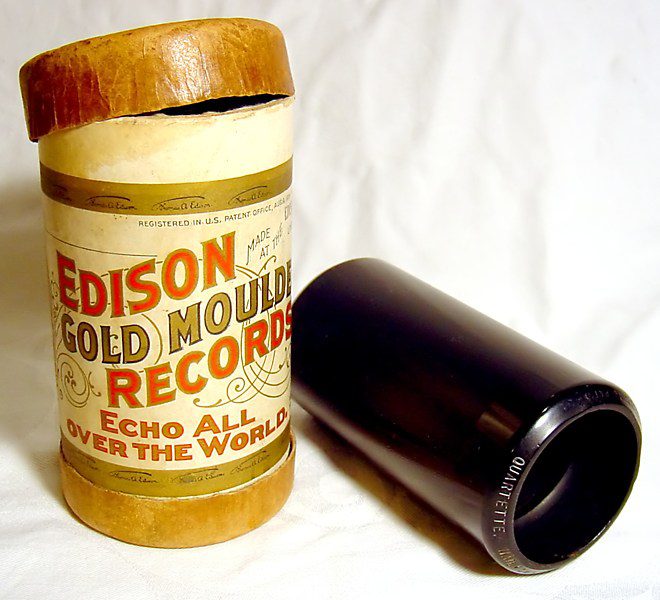

Their website features a growing mountain of streaming and downloadable songs that were originally released on fragile

Their website features a growing mountain of streaming and downloadable songs that were originally released on fragile