Over sixty years ago, in November 1963, President John F. Kennedy took a fateful trip to Texas. It would be the last of his life. The trip had four planned stops: San Antonio, Houston, Dallas, with a final planned fundraiser dinner in Austin. In the days after his shocking assassination, JFK was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Four years later in 1967, he was reinterred in his final resting place, marked by the Eternal Flame at the official presidential gravesite. The evolving design of the gravesite at Arlington had been publicized after his initial burial. However, behind the scenes, plans developed for an encircling memorial artwork. This missing wreath has remained undisclosed for decades.

With the Oak Spring Garden Foundation, I revealed the story of “The Missing Wreath: On JFK’s Grave & Mrs. Mellon’s Maquette” in an article published this fall in Ploughshares (the full text can be read here). Told as a detective narrative, it is woven like the structure of a wreath, exploring the planning, creation, and eventual disappearance of the artwork over time.

A short version of the story goes like this:

After JFK’s assassination and his initial interment in Arlington National Cemetery in November 1963, an architectural firm owned by John (Jack) Warnecke was commissioned to design the formal gravesite. Detailed research reports were created in conjunction with consultations by prominent family, scholars, architects, art critics, and clergy, along with a public exhibit of design plans at the National Gallery of Art and coverage in major news outlets. First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy wanted the gravesite to be publicly accessible yet personal and intimate as befitted a family grave. In 1964, she designated her close confidant, Rachel “Bunny” Lambert Mellon—who had designed JFK’s beloved White House Rose Garden—to represent Jackie’s wishes in the grave design.

With her sophisticated landscaping eye, Bunny softened Warnecke’s design around the Eternal Flame. As the final reinterment approached in 1967, she also worked behind the scenes on a secret memorial sculpture with another close confidant: the French-born Tiffany jewelry designer, Jean Schlumberger.

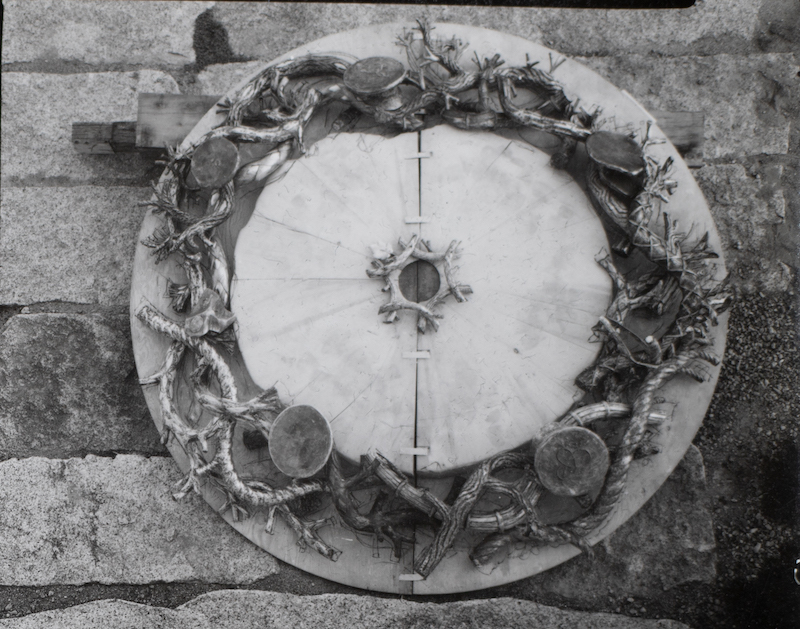

Bunny Mellon and Jean Schlumberger took as inspiration a wreath of military hats around the Eternal Flame that had been laid by JFK’s funerary Honor Guard in an impromptu gesture at his initial interment. Robert “Bobby” Kennedy, JFK’s brother, had been so moved by the gesture that he said the hats should remain around the grave until they “crumble to dust.” By 1969, the memorial wreath had been secretly made by French-born sculptor Louis Féron. Yet due to series of events and issues that delayed installation, the sculpture went missing by the early 1970s and was essentially lost to time—until it was rediscovered earlier this year.

Through the diligent sleuthing of Elinor Crane and Nancy Collins at the Oak Spring Garden Foundation (the Mellon’s former estate outside Upperville, VA), and with thanks to the memory of a stonemason named Tommy Reed, who had worked for essentially a half-century at Oak Spring, the lost artwork was finally found after a multi-year search. It was found disassembled in packing crates in an offsite storage facility at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum.

Originally written when the artwork was still missing, the story of “The Missing Wreath” aimed to inspire a search for the lost sculpture. In the process of writing, the search to me became a meditation on who and what gets lost and found in retellings of history. As I wrote in the longer article:

“Historical artifacts never exist in a vacuum, and inanimate objects have lives and even afterlives. Public and private events color retellings; an artwork can be curated dozens of ways, even to the point of disappearing behind variations of accounts. The aura around the memorial wreath’s absence makes it almost more powerful than if it were present. When public celebrity is involved, when privacy is fiercely guarded, when privilege can determine what is noticed or neglected or even erased, stories can constellate between private records and the public imagination … Histories can get lost between lines and behind headlines—just as a crumbling stone maquette in a rural cemetery can lie for decades without notice.”

In the two years since “The Missing Wreath” was finished and accepted for publication by Ploughshares, additional puzzle pieces have emerged from different corners of the country, aiding in the search for the artwork’s final resting place. A brief coda notes the memorial’s rediscovery, highlighting its journey from lost to found, while leaving room for future historians.

As I reflect back on this remarkable story, what remains of interest to me are different ways to see the memorial wreath. Any history is always incomplete, as acts of remembering grow spaces for future storytellers to fill more gaps. With a nod to Wallace Stevens’ poem “13 Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” I offer here some frameworks for interpreting and re-interpreting the wreath:

1. Histories of Art and Design: JFK’s memorial wreath was co-created by the American gardener and philanthropist Rachel “Bunny” Lambert Mellon, French-born jewelry designer Jean Schlumberger, and French-born sculptor Louis Féron. When lines between artist, craftsman, and commissioner blur, who is credited as the creator of an artwork? How do historical traditions and cultural systems influence this valuation and reevaluation where art and design meet?

2. Histories of Labor: In addition to the co-creators in name, JFK’s memorial wreath owes much to contributions by highly skilled tradesmen including stonemasons, gardeners, servicemen, foundry workers, and more. The story of the missing wreath surfaced at the Oak Spring Garden Foundation (the former estate of Paul and Bunny Mellon in Virginia), thanks largely to a stonemason, who originally worked on a stone maquette in the early 1970s in the Oak Spring cemetery, where the sculpture briefly weathered. Since many people played a role in this memorial, how are such layers of labor credited?

3. Histories of Memorials: Plans for JFK’s Gravesite included commissioned reports in the 1960s by interdisciplinary critics and experts who considered distinctions among graves, memorials, and monuments in shaping the design. This was complemented by public-facing exhibits and family engagements with the process. Whether a national or personal memorial, how do incorporated elements do more than reflect a singular era to stand the test of time? Since the memorial wreath was not installed on JFK’s grave, how does its rediscovery offer a different reading of the same object in a different historical context?

4. Histories of Cemeteries: Multiple cemeteries in Virginia help to illuminate the story of the missing wreath: Arlington National Cemetery (where JFK is buried), Oak Spring’s Fletcher Cemetery (where the stone maquette was constructed based on JFK’s grave), Trinity Episcopal Church Cemetery (where the Mellons are buried), not to neglect other marked graves, along with unmarked cemeteries in neighboring mountains (largely interring free Black communities). Cemeteries balance preservation of memories with residual presence of physical bodies, cycles of life and death, shaped by beliefs about afterlives rooted in culture and ecology. JFK’s Gravesite sits in a national cemetery; he is one of only two presidents buried at Arlington. How do considerations of burial and commemoration reflect not only the person who died but also the values of the living?

5. Histories of Gardens: Bunny Mellon designed JFK’s White House Rose Garden during the president’s life, his Gravesite at Arlington after his death, and later the bayside grounds in Boston for his Presidential Library and Museum. After her death, the Mellon estate at Oak Spring transitioned from a private estate into a “garden foundation” to cross-pollinate the humanities, arts and sciences. One of its responsibilities includes stewarding the property’s cemetery, which caught the attention of Elinor Crane. Crane began asking questions about the crumbling stone maquette and enlisted Nancy Collins, the Foundation’s archivist, to help her search. Histories of gardens and cemeteries overlap. As landscapes change over time, how do attentions to plants help to support living histories and reparative futures, including attending to climate change?

6. Histories of Materials: JFK’s grave is composed of engraved slate headstones around a large round stone sourced from New England, in a sea of wavy pink granite, surrounded by specimen trees and other signature plantings. The design of the memorial wreath symbolically interweaves materials from bamboo to rope, driftwood to military hats, which inspired the wreath after JFK’s Honor Guard laid their hats in that shape at his initial interment. His memorial artwork was cast at a metal foundry and brought outside for a brief time to weather on an oyster shell stone maquette at Oak Spring. Considering both natural and manmade resources, how does materiality contribute to this story of the memorial wreath?

7. Histories of Ecology: After her multi-year search for the missing memorial wreath, Elinor Crane finally witnessed the artwork in early 2024 disassembled and crated at the JFK Presidential Library and Museum in Boston. On one of the disassembled pieces, she spied an unexpected detail: some bird droppings which she surmised came from Oak Spring when the memorial had been laid to rest for a short time on the outdoor stone maquette in the cemetery in the early 1970s. Since Oak Spring has transitioned from a private estate to a garden foundation to focus on cross-pollinating research, would it be possible to test and trace those droppings to identify the avian species? What foods might that bird have eaten, and does its kin still migrate through this ecosystem? This detail may seem insignificant but reveals the living world that surrounds such memorials.

8. Histories of Lands (Ancestral, Colonized, Enslaved, Emancipated, Legislated): Established in 1864, Arlington National Cemetery is relatively young. It occupies land once owned by Robert E. Lee, which was requisitioned during the Civil War as a national burial ground. On the heels of the Emancipation Proclamation, part of the land was designated Freedman’s Village to support free Black women and men escaping enslavement. In centuries before colonization, the intersecting waterways of the Potomac and Chesapeake region served as homeland for hundreds of Indigenous communities. How are these ancestral lands recognized and represented in national and regional cemeteries, and who else may be buried in marked and unmarked graves in and beyond this region?

9. Histories of Witnesses: Most of JFK’s contemporaries have died, but after the memorial wreath was found in 2024, Elinor Crane and Nancy Collins learned that an important member of JFK’s funeral Honor Guard still lives. James L. Felder was only the tenth Black American to serve with the Honor Guard (with the other nine preceding him by only months), and he wrote an account of his experience, I Buried John F. Kennedy (1994). When the Oak Spring Garden Foundation gathered experts for a private meeting in September 2024 to share news of the lost-and-found memorial, Felder spoke about his experience and also shared his personal album of JFK’s funeral, made for him personally by First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy. Attendees also received a copy of Felder’s book with an advanced copy of “The Missing Wreath.” His album was reproduced for an exhibition on the memorial wreath that will run at the Oak Spring Garden Foundation from October 2024 into 2025. “The Untold Story of a Lost Memorial” exhibition invites attendees to share their own intersecting memories.

10. Histories of Libraries & Museums: Many museums and libraries figure in this story, including the Oak Spring Garden Library, Museums of Fine Arts in Virginia and Boston, the JFK Presidential Library and Museum, and others. Collections are never complete by themselves. Primary research often requires years for researchers to piece together a story. Large collections may take years to process, catalogue, and create finding aids to make items accessible. Versions of cataloguing can leave items relatively invisible. Conservation and preservation of a single item may take months or longer. Events like a global pandemic can separate curators from collections. Scholarly trends may neglect aspects of objects that hide in plain sight. Historical events influence why items were collected in the first place, leaving gaps in historical records. Collaborations help to reconnect parts that have been disassembled over time. How do related histories influence the lost-and-found memorial wreath and other aspects that may be missing from this story?

11. Histories of Speculative Futures: If the memorial wreath been installed after JFK’s reinterment, what would its reception have been in the era of the late 1960s or early 1970s? Would it have distracted from the timeless simplicity of the Eternal Flame, and what other unrealized memorial plans for the president’s grave lie buried in other archives? Now that the memorial wreath has been found, what are its possible futures, from its current resting place disassembled in Boston to an anticipated exhibition reassembled in Virginia, or otherwise? Why does the specter of JFK’s unrealized presidency continue to haunt our current moment, including vulnerabilities around civil rights and other social concerns that remain pressing issues? Beyond surmising what the world might have been if JFK had survived, would it be more helpful to consider: What descendants have we become, and what kind of ancestors do we wish to be?

12. Symbolic Histories: Many symbols are woven into JFK’s memorial wreath—military hats, ropes, driftwood, a leaf, and more—not to neglect the symbol of the wreath itself. Why have the symbol of wreaths played such an important role over time? What does the choice of a memorial in the shape of a wreath resembling a crown of thorns offer to this larger encircling story? Now that over a half-century has passed since the memorial wreath was created, what symbols still carry resonance or not, depending on the eye (and age and background) of the beholder? Beyond the memorial wreath, how might the living symbol of the Eternal Flame illuminate a path forward, among other eternal flames that have existed across centuries and cultures?

13. Public Histories and Public Memories: For many, the memory of that day remains remarkably vivid. If you were alive in 1963, consider what do you remember? If you weren’t alive then, ask someone who was to share generational knowledge—not only about JFK but also about their daily lives. How do generations connect to learn about the arc of evolving and intersecting histories? What other questions arise? What knowledges emerge by sharing these stories? As I wrote:

“Even as this story tells the arc of an artwork that went missing, it is as much if not more a story of those who co-created a memorial and who cared to go searching for an artifact that got lost, about the ephemeral or privileged materiality of human lives, how cultural collections are acquired and stewarded in ways that evolve, laying groundwork for future researchers and historical understandings.” ~ GEH, “The Missing Wreath”

These are 13 ways of looking at JFK’s lost-and-found memorial wreath, offering more questions than answers. There are surely more. But these questions provide a starting point to look again at this traumatic and critical moment in modern American history, as we work to imagine and co-create possible futures.

Gretchen Ernster Henderson is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Texas at Austin and writes across environmental arts, cultural histories, and integrative sciences. Her publications, exhibitions, and performances include five books, arts media, and opera libretti. She previously served as Associate Director for Research at the Harry Ransom Center at UT-Austin and Co-Director of a National Endowment for the Humanities Institute on Museums: Humanities in the Public Sphere at Georgetown University with UC-Santa Cruz.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

Banner picture: Oak Spring Garden Library, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, VA. Photo by author, April 2021.