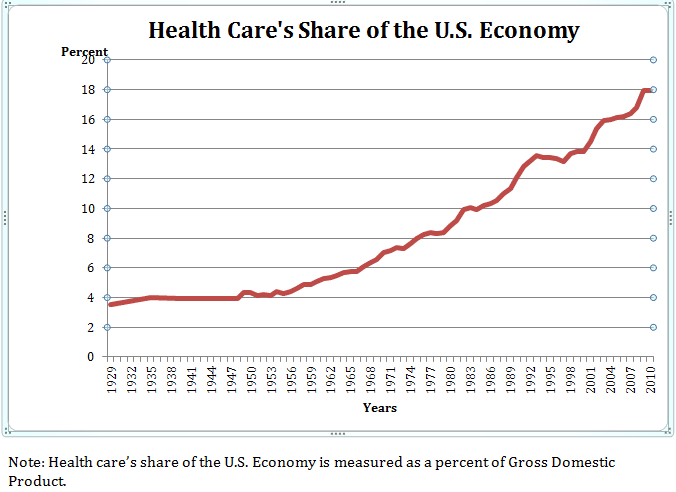

One subtext of last week’s Supreme Court decision on health care was a debate about how economic equality should or should not be regulated by the Constitution. Our colleague, constitutional historian William Forbath, has an op-ed in the New York Times today, discussing the history of such regulation and suggesting ways to address the growing disparity between rich and poor in the US:

“The Constitution… promises real equality of opportunity; it calls on all three branches of government to ensure that all Americans enjoy a decent education and livelihood and a measure of security against the hazards of illness, old age and unemployment — all so they have a chance to do something that has value in their own eyes and a chance to engage in the affairs of their communities and the larger society. Government has not only the authority but also the duty to underwrite these promises.”

For more on the history of the Constitution, take a look at this exhibit from the National Archives: A More Perfect Union: The Creation of the U.S. Constitution.