by Yana Skorobogatov

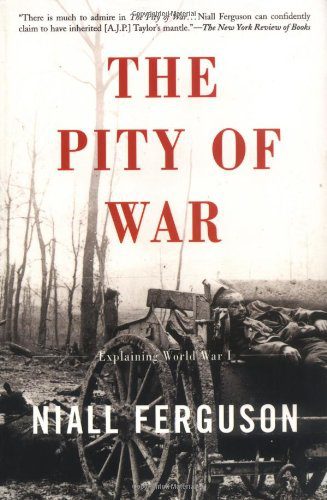

In The Pity of War, Niall Ferguson dedicates fourteen essays to addressing the major historical issues associated with the First World War.The essays fall into three broad categories: war origins, execution, and aftermath. Overt militarism, Germany’s ascent to power, alliance-based foreign policies, arms racing, and British intervention are issues covered in the first part of the book, while wartime enthusiasm, propaganda, economy, and military strategy are discussed in the second. The final chapter, on the Versailles Treaty, advances the controversial argument (one that rests on a long-winded condemnation of John Maynard Keynes) that the peace terms were not unprecedented in their harshness and that German hyperinflation was due to irresponsible fiscal policies adopted by the Germans themselves. The question that informs Ferguson’s analysis is: who is to blame for the war? Ferguson is unambiguous in his belief that British statesmen overestimated their alliance obligations and the extent of the German threat, which led them to mistakenly intervene in and transform a regional conflict into a global war. This assessment colors each of the book’s chapters and leads the author to put forth many bold, unorthodox, yet startlingly fresh arguments about a topic that many of today’s historians have written off as overdone.

After finishing the book, the reader will realize that its subtitle, “Explaining World War I,” is far more clever than it appears at first glance. The Pity of War offers not quite a history of the First World War, but rather a history of Great Britain and the First World War; for Ferguson, the two are inseparable. In his eyes, a proper explanation of World War I must dedicate a significant portion of its narrative to Great Britain. This would have been construed as an outdated approach – most recent scholars of empire have stopped writing books centered in the City of London – if not for the innovative mix of social and cultural history added to Ferguson’s standard economic and military analyses. Fascinating chapters on the media purveyors of wartime propaganda, enthusiasm on the home front, and soldier motivation humanize other chapters that depict army recruits as little more than another item on the British government’s grocery list for war material.

After finishing the book, the reader will realize that its subtitle, “Explaining World War I,” is far more clever than it appears at first glance. The Pity of War offers not quite a history of the First World War, but rather a history of Great Britain and the First World War; for Ferguson, the two are inseparable. In his eyes, a proper explanation of World War I must dedicate a significant portion of its narrative to Great Britain. This would have been construed as an outdated approach – most recent scholars of empire have stopped writing books centered in the City of London – if not for the innovative mix of social and cultural history added to Ferguson’s standard economic and military analyses. Fascinating chapters on the media purveyors of wartime propaganda, enthusiasm on the home front, and soldier motivation humanize other chapters that depict army recruits as little more than another item on the British government’s grocery list for war material.

Ferguson deserves praise for a book that is unique in scholarly insight, rigorous in its treatment of the secondary literature, and accessible to a non-academic reader. His excellent use of popular literature – the wartime poems, books, and songs he read and heard while growing up in England – testify to his personal connection to his subject. The book’s most convincing arguments are those that rely on evidence of Cabinet, Parliamentary, and popular political attitudes that contradict previous scholars’ explanations for British intervention in the conflict. For example, Ferguson argues that a militant culture, embodied by Army Leagues and immensely popular spy books, cannot even partially explain British politicians’ decision to declare war against Germany because such a culture lacked an electoral following. To the contrary, many of the most influential politicians at the time worked to uphold a liberal tradition defined by an aversion to excessive military spending and a historic dislike of a large army. Theorists like J.A. Hobson, whose widely-read books outlined the malign relationship between a nation’s financial interests, imperialism, and war, helped anti-militarist socialist parties gain a strong electoral following on the eve of war. Ferguson makes an interesting distinction between pacifism and anti-militarism, of which social and cultural historians should take note. Other anecdotes are less worthy of emulation. His strong belief that Germany would have guaranteed France and Belgium’s territorial integrity in exchange for British neutrality comes across as extremely optimistic, if not baseless. Ferguson seems naive to assume that a “Middle European Empire of the German Nation” could be maintained without German infringement on a rival nations’ sovereignty. Nazi Germany’s continental ambitions, though qualitatively different from Mitteleuropa, offer a hint to what France and Belgium’s fates would have been like had plans for a German-dominated and exploited Central European union been realized.

Ferguson deserves praise for a book that is unique in scholarly insight, rigorous in its treatment of the secondary literature, and accessible to a non-academic reader. His excellent use of popular literature – the wartime poems, books, and songs he read and heard while growing up in England – testify to his personal connection to his subject. The book’s most convincing arguments are those that rely on evidence of Cabinet, Parliamentary, and popular political attitudes that contradict previous scholars’ explanations for British intervention in the conflict. For example, Ferguson argues that a militant culture, embodied by Army Leagues and immensely popular spy books, cannot even partially explain British politicians’ decision to declare war against Germany because such a culture lacked an electoral following. To the contrary, many of the most influential politicians at the time worked to uphold a liberal tradition defined by an aversion to excessive military spending and a historic dislike of a large army. Theorists like J.A. Hobson, whose widely-read books outlined the malign relationship between a nation’s financial interests, imperialism, and war, helped anti-militarist socialist parties gain a strong electoral following on the eve of war. Ferguson makes an interesting distinction between pacifism and anti-militarism, of which social and cultural historians should take note. Other anecdotes are less worthy of emulation. His strong belief that Germany would have guaranteed France and Belgium’s territorial integrity in exchange for British neutrality comes across as extremely optimistic, if not baseless. Ferguson seems naive to assume that a “Middle European Empire of the German Nation” could be maintained without German infringement on a rival nations’ sovereignty. Nazi Germany’s continental ambitions, though qualitatively different from Mitteleuropa, offer a hint to what France and Belgium’s fates would have been like had plans for a German-dominated and exploited Central European union been realized.

Photo credits:

Realistic Travels, “Three British soldiers in trench under fire during World War I,” 15 August 1916 (Image courtesy of The Library of Congress)

McLagan & Cumming, “The tank tour. Buy national war bonds (£5 to £5000) and war savings certificates,” 1918, Scottish War Savings Committee (Image courtesy of The Library of Congress)

You may also like:

Lior Sternfeld’s review of Erez Manela’s The Wilsonian Moment.

In his sharp analysis of Britain’s declining world system,

In his sharp analysis of Britain’s declining world system,

Thirty years earlier, on October 9, 1967, CIA-trained Bolivian Special Forces agents had captured and executed the thirty-nine-year-old revolutionary before dumping his body in a shallow pit near a dirt runway. While writing

Thirty years earlier, on October 9, 1967, CIA-trained Bolivian Special Forces agents had captured and executed the thirty-nine-year-old revolutionary before dumping his body in a shallow pit near a dirt runway. While writing