For too many of us, the events of September 11, 2001 have been embalmed in political rhetoric so thick, that we have lost sight of what happened that day and what it meant. Our greatest city was attacked. Our capital was attacked. 2996 people died.

In addition to our regular programming I want to commemorate that day by re-posting one of the articles from our tenth anniversary series in 2011.

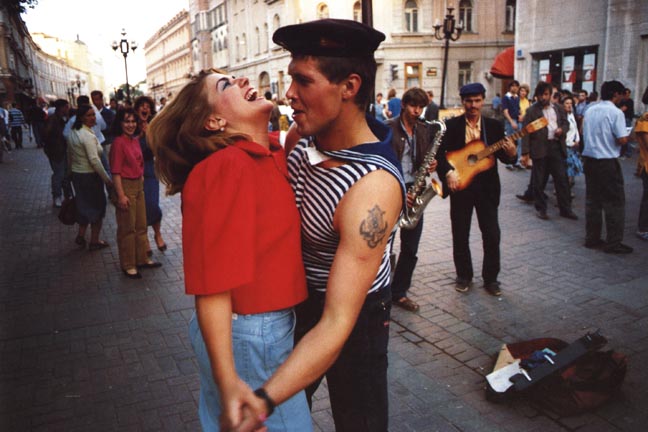

Let’s end our week of commentary on September 11, 2001 with some images. Visualizing and re-visualizing shape our memories differently than describing and talking. Poetry, photography, and song open up different dimensions to understanding the past. Images keep the past present in different ways as well.

It’s probably fair to say that everyone alive in 2001 can see pictures from that day. And that looking at them again makes everything we’ve read take on new meanings. My then-second-grader still pictures a drawing he made in school of smoke coming from the two “Thin Towers.” The image that first made me aware, viscerally aware, of the magnitude of the attack is a photograph by Marty Lederhandler of three New Yorkers, absolutely horrified by what they were seeing, but they’re standing in front of St Patrick’s Cathedral, all the way up on 51st St, miles away. Here is The New York Times’ collection of photographs from September 11 and the days that followed. (And here is a collection of Times’ articles.)

Frank Guridy shared with us a poem he reads in his classes every year on September 11. “Alabanza: In Praise of Local 100,” by Martín Espada is dedicated to the restaurant workers at Windows on the World. It is a wonderful elegy both for its affection for the international, early-morning world of a restaurant kitchen and for the music — “the kitchen radio/ dial clicked even before the dial on the oven” — that bridged gaps of language and class; and distance.

And finally, Paul Simon. Watch and listen to this perfect rendition of a perfect song, perfectly attuned to the moment, sent to us by Richard (Kip) Pells. “The Sound of Silence” on 9/11 at Ground Zero.

[jwplayer mediaid=”5250″]

Joe and his nephew Steve are searching for another Chan, their friend Chan Hung, who seems to have disappeared with $4,000 of their cash. Along the way, they encounter a gallery of Chinatown personalities and settings, revealing aspects of the district that are rarely visible to visiting tourists. They venture past the bustling restaurants and the pagoda roofs and dragon-embellished streetlights of Grant Avenue into the tight quarters of greasy commercial kitchens; the packed fish markets and grocery stores of Stockton Street; narrow, laundry-festooned residential alleyways; a local senior citizens center; and the Neighborhood Language Center offering English classes for new arrivals.

Joe and his nephew Steve are searching for another Chan, their friend Chan Hung, who seems to have disappeared with $4,000 of their cash. Along the way, they encounter a gallery of Chinatown personalities and settings, revealing aspects of the district that are rarely visible to visiting tourists. They venture past the bustling restaurants and the pagoda roofs and dragon-embellished streetlights of Grant Avenue into the tight quarters of greasy commercial kitchens; the packed fish markets and grocery stores of Stockton Street; narrow, laundry-festooned residential alleyways; a local senior citizens center; and the Neighborhood Language Center offering English classes for new arrivals.

that authoritarian governments were common in the twentieth century, lasted for several generations, and some, like the authoritarian government of North Korea, continue to affect global affairs in the new millennium. It is also increasingly evident that popular participation, and not just dictators’ decrees, helped build and dismantle authoritarian regimes.

that authoritarian governments were common in the twentieth century, lasted for several generations, and some, like the authoritarian government of North Korea, continue to affect global affairs in the new millennium. It is also increasingly evident that popular participation, and not just dictators’ decrees, helped build and dismantle authoritarian regimes.