By Frank A. Guridy

On April 22, 1930, Lalita Zamora, an Afro-Cuban woman in Havana, wrote a letter to Langston Hughes, the famous “Blues Poet” of the Harlem Renaissance, to thank him for sending her copies of his poetry books. Zamora had met Hughes during his recent trip to Cuba. Her letter, which was written in English, expressed her admiration for the way his writing style effectively conveyed to “the reader the sensation and feelings of the desires, hopes, love and ambitions of our race.” Zamora’s usage of the words “sensation” and “feelings” is striking. Such words convey her belief that Hughes’s poems authentically represented the emotions and aspirations of those of her “race” and perhaps even herself.

Zamora’s letters are a few of the fascinating communications that Hughes received from Cuban fans of his work, a number of them coming from Afro-Cubans. This “fan mail,” along with a host of other materials that exist in the Langston Hughes Papers at Yale University’s Beinecke Library, documents the poet’s relationships with Cuban artists, intellectuals, and readers. The relationships that Langston Hughes developed with Afro-Cubans exemplify the personal and artistic connections that helped shape the political strategies of both Afro-Cubans and black Americans as they attempted to overcome a shared history of oppression and enslavement. These encounters illustrate the significance of cross-national linkages to the ways black populations in both countries negotiated the entangled processes of U.S. imperialism and racial discrimination. As a result of these relationships, Afro-Cubans and African-Americans came to identify themselves as part of a transcultural African diaspora, an identification that did not contradict their ongoing struggle for national citizenship.

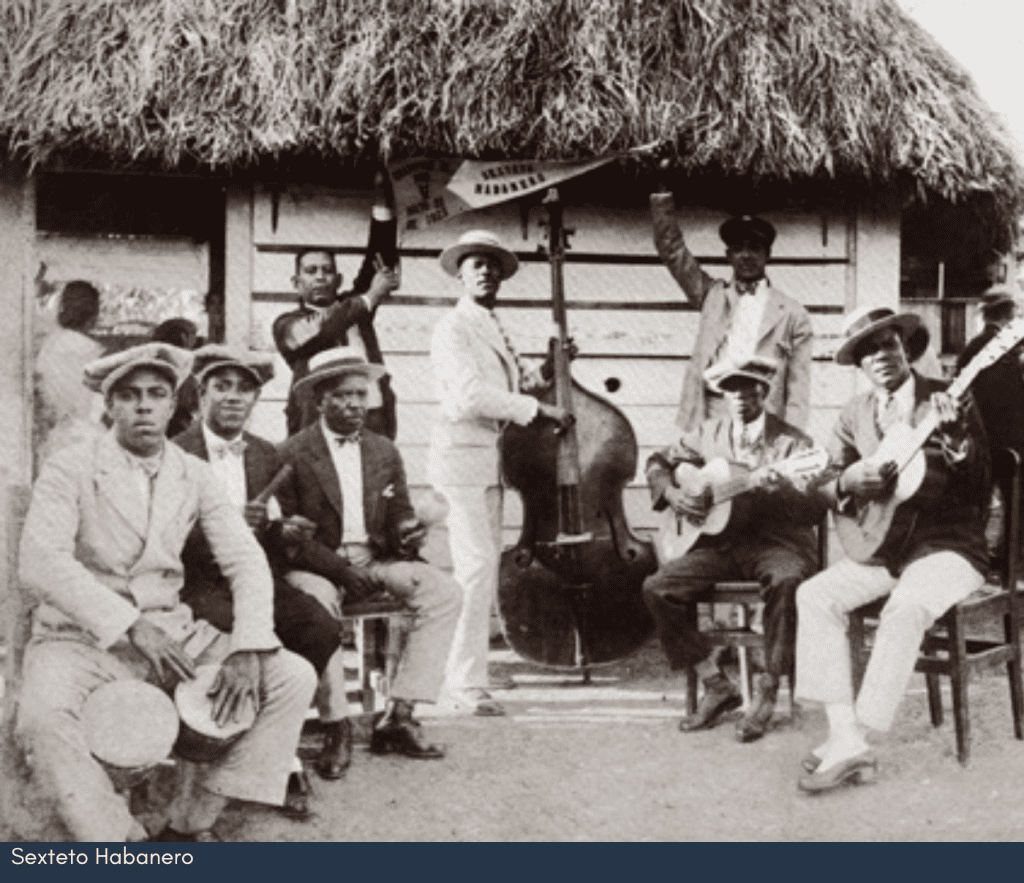

Hughes’s international stature in the 1930s enabled him to play a key role in establishing African-American relations with Cubans of African descent in this period. While his role in the Harlem Renaissance is well documented, his important work as a promoter and translator of Afro-Cuban poetry and art is less well known. His experience living in Mexico as a youth with his father gave him a unique transcultural background in Latin American and U.S. American cultures, allowing him to translate Afro-Cuban writings for African-American readership. During his trips to the island in 1930 and 1931, Hughes became acquainted with many of the leading members of the Cuban intelligentsia, including José Antonio Fernández de Castro, the noted writer and magazine editor, Gustavo Urrutia, the black journalist, and Nicolás Guillén, the Afro-Cuban poet. Guillén’s poetry, like Hughes’s verse, popularized the use of black vernacular languages in poetry and song, thereby illustrating the synergies between the Harlem Renaissance and the Afro-Cubanist movement. Guillén crafted poems inspired by the son, the African-derived musical genre that spread throughout the island during the 1920s.

Correspondence between Hughes and his fans in Cuba illustrate the perception among African-descendants in both Cuba and the United States of a commonality of experiences across national and cultural differences. This is clear in the ways Cuban readers viewed the relationship between Guillén’s and Hughes’s poetry. A 1930 letter to Hughes from Gustavo Urrutia, hailed the publication of “eight formidable negro poems written by our Guillén. They are real Cuban negro poetry written in the very popular slang. They are the exact equivalent of your ‘blues,’” exalted Urrutia.

Yet the Cuban reception to Hughes was not limited to correspondence that commented on his poetry. For example, letters from Afro-Cuban women illustrate the ways romantic feelings infused their desire to connect with the attractive man from another part of the African diaspora. A few weeks after Hughes’s 1930 visit, Caruca Alvarez, a woman living in Havana who described herself as a “romantic,” wrote Urrutia in an effort to obtain the Blues Poet’s address in the U.S. “As one of the first admirers of his race and as a Cuban woman, I would very much like to be Langston’s spiritual friend,” Alvarez wrote.

A more aggressive series of communications came from Fara Crespo, another one of the Blues Poet’s female “admirers” who hoped to be his “friend.” Soon after Hughes’ departure from Cuba, Crespo wrote to express her admiration for the “poet of the ‘spirituals,’” as she called him, and to make a request. “I, a young Cuban woman admirer of one who is brave enough to exclaim: I want to be truly black, would like to be able to call myself the friend of the poet Langston Hughes!” Like Alvarez, Crespo was drawn to Hughes’s explicit identification with blackness, citing a public interview Guillén conducted with Hughes, in which he stated, “I want to be truly black.” Yet, her attractions ran deeper. While acknowledging the boldness of her explicit request to ask for the “friendship of a man,” she felt confident that Hughes would not be turned off because he “belong[ed] to this modern era free of all forms of prejudice and marked by material, intellectual, and moral freedom.” Indeed, Crespo fashioned herself as a woman of the modern era. “When you arrived in Havana you attracted my attention,” Crespo wrote, “because you were what I had been looking for and for this reason I write you with the hope of having [you] as a true friend.”

The letters from Alvarez and Crespo convey the complex motivations at work among those who expressed their admiration for the Blues Poet, including the desire to know a celebrity, romantic attraction, and intellectual curiosity. They also reveal how Hughes’s Afro-Cuban admirers sought to navigate cultural differences by relying on expressions of desire infused by a romantic attraction. I read these letters as evidence of the yearnings embedded in Afro-diasporic interaction and indeed most motives for affiliation—desires that ranged from Hughes’s wish to be “truly black,” to Crespo’s yearnings to be “the friend of Langston Hughes.” Crespo and Alvarez’s inattention to Hughes’s poetry showed that, like many of his Cuban fans, they sought to connect with the famous Blues Poet because they were attracted to his physical and symbolic roles as a “colored” man of letters from the United States. Perhaps most importantly, Crespo’s and Alvarez’s letters illustrate how black Cuban women could use the epistolary form to engage with the writers of the Harlem and Havana movements as agents, rather than as mere objects, of desire. These letters need not be dismissed as mere “fandom,” but rather seen as evidence of the ways women of African descent, excluded by the male-dominated literary scene in Cuba, sought to engage with the writers they found appealing. Moreover, they also show how Afro-Cubans and African Americans used whatever means at their disposal—broken versions of English and Spanish, or communications of affect—to forge commonality across difference.

For more on the transnational diaspora forged by Afro-Cubans and African-Americans, see Frank A. Guridy’s Forging Diaspora: Afro-Cubans and African-Americans in a World of Empire and Jim Crow

Michael Gomez, Reversing Sail: A History of the African Diaspora, (2004).

Gomez’s survey of the history of Africans and descendants from continental origins to the end of the twentieth century is an excellent introduction to the history of the African Diaspora from a global perspective.

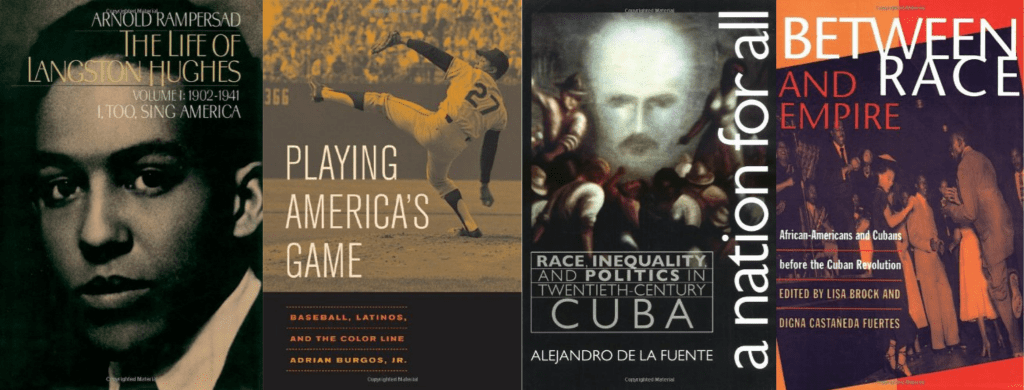

Arnold Rampersad, The Life of Langston Hughes: I, Too Sing America, 1902-1941, Vol. 1, (1986).

This biography by the distinguished literary scholar is still the definitive study of the life and work of the famous American poet.

Alejandro de la Fuente, A Nation for All: Race, Inequality, and Politics in Twentieth Century Cuba, (2001).

De la Fuente’s study examines the question of racial discrimination in Cuban politics before and after the triumph of Fidel Castro’s revolution.

Lisa Brock and Digna Castañeda Fuertes, ed. Between Race and Empire: African-Americans and Cubans before the Cuban Revolution (1998).

A pathbreaking collection of essays by Cubans and American scholars that illustrates the various realms of African-American engagements with Cubans, from the baseball diamond to music and politics.

Adrian Burgos, Jr. Playing America’s Game: Baseball, Latinos, and the Color Line (2007).

The definitive study of Latinos in major league baseball before and after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947. Many of these Latinos were Cubans. Those defined as white could play in the major leagues while those who designated black were relegated to the Negro Leagues.

Photo credits:

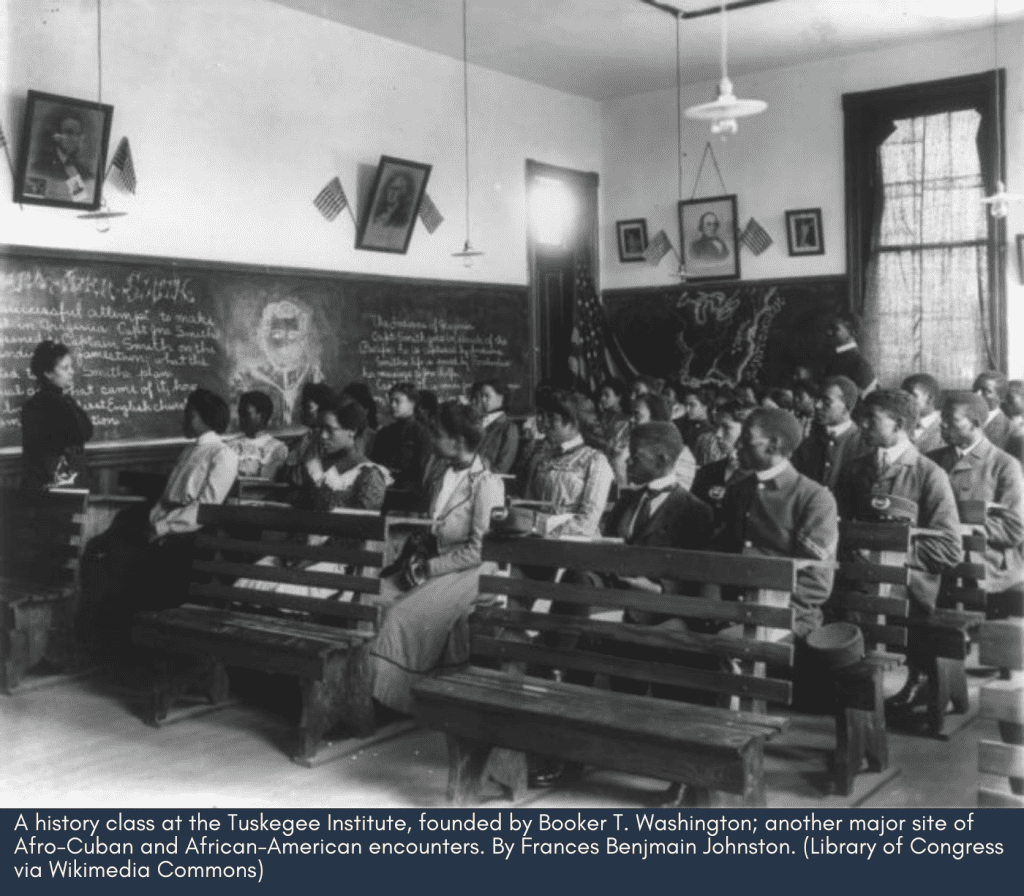

A history class at the Tuskegee Institute, founded by Booker T. Washington; another major site of Afro-Cuban and African-American encounters. By Frances Benjmain Johnston. Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons

Langston Hughes, by Carl Van Vechten, Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons Sexteto Habanero, via Wikimedia Commons

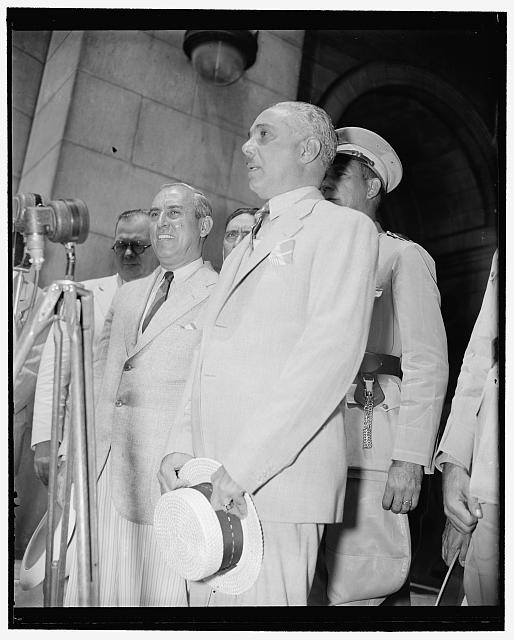

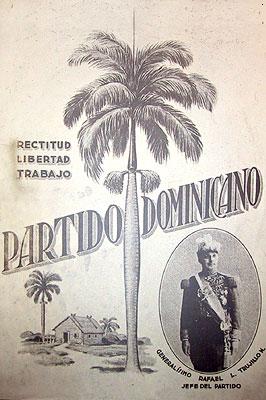

A light-skinned mulatto with Haitian ancestry, Trujillo rose from obscurity as a sugar plantation guard to establish one of Latin America’s most enduring dictatorships. His appetite for women was legendary and common belief held that he never sweated. Trujillo’s minions, and even foreign governments, lavished him with praise and an array of titles from Generalissimo to Benefactor of the Fatherland to Restorer of Financial Independence. However, outside portrayals of Trujillo as a make-up wearing megalomaniac and revelations of his regime’s oppression, many questions remain about the mechanisms of state power and relations between the Dominican populace, Trujillo, and the state. In The Dictator’s Seduction, Lauren Derby uncovers the cultural economy “that bound Dominicans to the regime.” She reinterprets the regime’s theatricality – pageants, parades, and the practices of denunciation and public praise – as critical in obscuring the inner workings of the regime and argues that the Trujillato gained and maintained the support of the masses, albeit in attenuated form, by creating a new middle class and co-opting Dominican understandings about the embodiment of race, gender, sexuality, and the process of community formation.

A light-skinned mulatto with Haitian ancestry, Trujillo rose from obscurity as a sugar plantation guard to establish one of Latin America’s most enduring dictatorships. His appetite for women was legendary and common belief held that he never sweated. Trujillo’s minions, and even foreign governments, lavished him with praise and an array of titles from Generalissimo to Benefactor of the Fatherland to Restorer of Financial Independence. However, outside portrayals of Trujillo as a make-up wearing megalomaniac and revelations of his regime’s oppression, many questions remain about the mechanisms of state power and relations between the Dominican populace, Trujillo, and the state. In The Dictator’s Seduction, Lauren Derby uncovers the cultural economy “that bound Dominicans to the regime.” She reinterprets the regime’s theatricality – pageants, parades, and the practices of denunciation and public praise – as critical in obscuring the inner workings of the regime and argues that the Trujillato gained and maintained the support of the masses, albeit in attenuated form, by creating a new middle class and co-opting Dominican understandings about the embodiment of race, gender, sexuality, and the process of community formation.

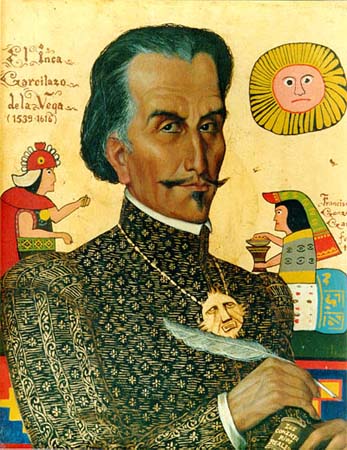

Cope overturned the idea that racial identity in colonial Mexico was “fixed permanently at birth” and argued that race was a versatile identity that could be “reaffirmed, modified, manipulated, or perhaps even rejected.” The unfixed nature of identities assumed and performed by individuals and groups in colonial Latin America beyond Mexico City is the subject of the collection of essays edited by Andrew Fisher and Matthew O’Hara recently published as Imperial Subjects: Race and Identity in Colonial Latin America.

Cope overturned the idea that racial identity in colonial Mexico was “fixed permanently at birth” and argued that race was a versatile identity that could be “reaffirmed, modified, manipulated, or perhaps even rejected.” The unfixed nature of identities assumed and performed by individuals and groups in colonial Latin America beyond Mexico City is the subject of the collection of essays edited by Andrew Fisher and Matthew O’Hara recently published as Imperial Subjects: Race and Identity in Colonial Latin America.

Many previous studies breezily pit “Islam” against the “West.” Sidestepping the assumption that the two categories are essentially different, GhaneaBassiri studies the actual lived tradition of Muslims in America instead of second-guessing their compatibility.

Many previous studies breezily pit “Islam” against the “West.” Sidestepping the assumption that the two categories are essentially different, GhaneaBassiri studies the actual lived tradition of Muslims in America instead of second-guessing their compatibility.

In the wake of the Russian launch of

In the wake of the Russian launch of