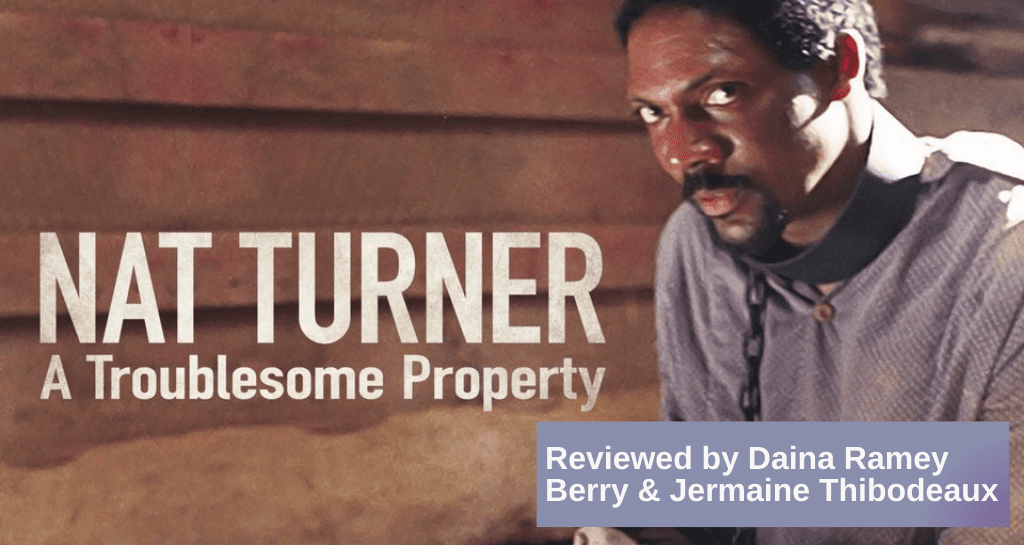

By Daina Ramey Berry and Jermaine Thibodeaux

This film tells the story of Nat Turner’s 1831 Virginia slave revolt. For years, historians have grappled with the details of the affair and debated about the ways Nat Turner should be remembered. For some, he was a revolutionary hero; for others, Turner was nothing more than a deranged, blood-hungry killer. After all, it was Turner’s rebellion that sent the South into a frenzy forcing southern legislatures and planters to harden their stances (and laws) on slavery. This PBS movie blends documentary narrative, historical re-enactment, and scholarly reflection to examine the various renditions of the revolt and to uncover the many faces of Nat Turner and slave resistance in general. Directed by Charles Burnett, this is a film worth watching for those interested in slavery, public history, and the history memory. As part of the Independent Lens series, the PBS website provides a wealth of historical material on Nat Turner, slave rebellion, and historical treatments.

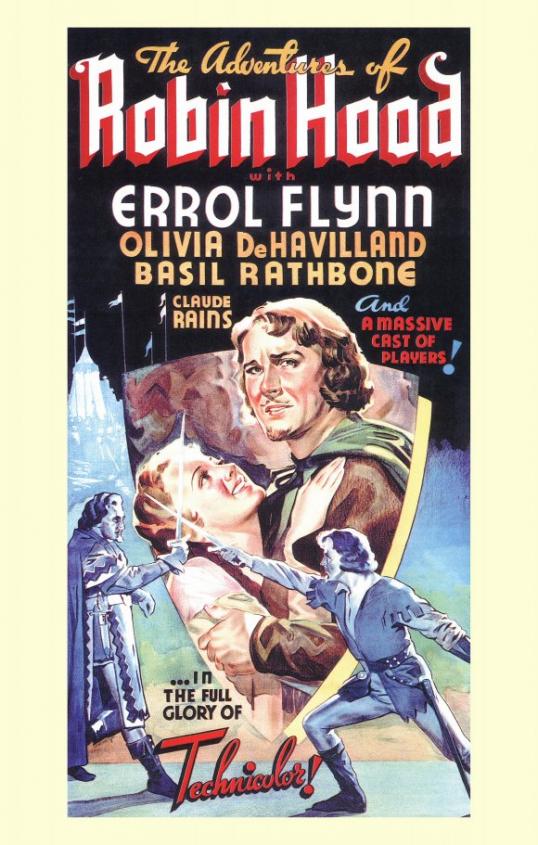

The production team included director Michael Curtiz and producer Hal B. Wallis, who later teamed up to create 1943’s enduring wartime romance Casablanca. Erich Wolfgang Korngold, one of the top film composers of the day, set The Adventures of Robin Hood to music. The film was shot in brilliant Technicolor on a then-exorbitant budget of two million dollars. It raked in twice that amount at the box office and went on to win three Oscars at the 11th Academy Awards.

The production team included director Michael Curtiz and producer Hal B. Wallis, who later teamed up to create 1943’s enduring wartime romance Casablanca. Erich Wolfgang Korngold, one of the top film composers of the day, set The Adventures of Robin Hood to music. The film was shot in brilliant Technicolor on a then-exorbitant budget of two million dollars. It raked in twice that amount at the box office and went on to win three Oscars at the 11th Academy Awards.

Commentators from the

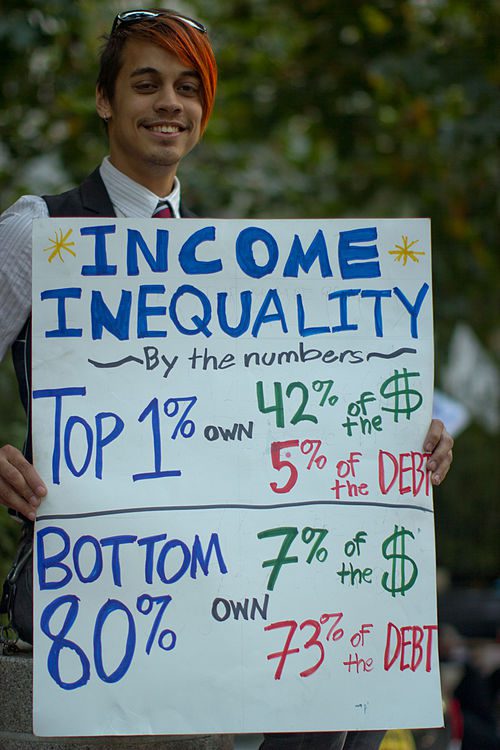

Commentators from the  Judith Stein, a historian at City College of New York who has visited the movement in Foley Park, expressed most clearly the liberal pessimists’ view in a magazine that, ironically, is called Dissent. “These kinds of endeavors have a long history in the United States,” Stein reminds her readers, “from the creation of utopian communities in the nineteenth century to the formation of communes in the 1960s and 1970s.” However, her point is not to celebrate Occupy Wall Street as the culmination of what came before. Rather, she warns that left-leaning movements’ “track record as a vehicle for change is poor.”

Judith Stein, a historian at City College of New York who has visited the movement in Foley Park, expressed most clearly the liberal pessimists’ view in a magazine that, ironically, is called Dissent. “These kinds of endeavors have a long history in the United States,” Stein reminds her readers, “from the creation of utopian communities in the nineteenth century to the formation of communes in the 1960s and 1970s.” However, her point is not to celebrate Occupy Wall Street as the culmination of what came before. Rather, she warns that left-leaning movements’ “track record as a vehicle for change is poor.” It would be foolish to describe Kazin and Stein’s warnings as cynical. Still some scholars, notably two from a younger generation, seem more optimistic about Occupy Wall Street, though they share the same concerns. In an interview with American Public Media’s Market Place, University of Texas historian Jeremi Suri told Kai Ryssdal, “Unfortunately they’re not offering any cohesive or coherent alternative to the capitalist system as we know it.” However, Suri ended on an optimistic note: “Give them some time.” On

It would be foolish to describe Kazin and Stein’s warnings as cynical. Still some scholars, notably two from a younger generation, seem more optimistic about Occupy Wall Street, though they share the same concerns. In an interview with American Public Media’s Market Place, University of Texas historian Jeremi Suri told Kai Ryssdal, “Unfortunately they’re not offering any cohesive or coherent alternative to the capitalist system as we know it.” However, Suri ended on an optimistic note: “Give them some time.” On

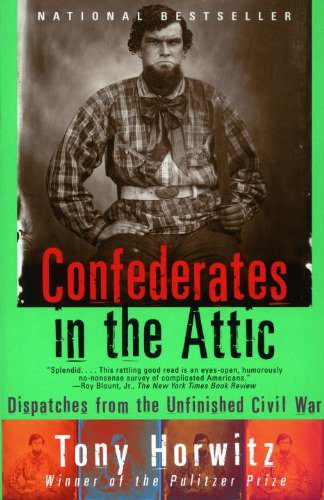

The noise came from an unexpected Civil War re-enactment being filmed outside of his bedroom window. Horwitz had once been a little boy who would spend hours engrossed in an old, enormous book of Civil War sketches, captivated by images of Yankee and Dixie soldiers engaged in battle. But despite spending a number of years working as a war correspondent, it was this surprise encounter with the “men in grey” that prompted Horwitz to turn the critical gaze of the journalist upon his own and his country’s enduring fascination with the bloody conflict that pitted American against American in 1861-1865.

The noise came from an unexpected Civil War re-enactment being filmed outside of his bedroom window. Horwitz had once been a little boy who would spend hours engrossed in an old, enormous book of Civil War sketches, captivated by images of Yankee and Dixie soldiers engaged in battle. But despite spending a number of years working as a war correspondent, it was this surprise encounter with the “men in grey” that prompted Horwitz to turn the critical gaze of the journalist upon his own and his country’s enduring fascination with the bloody conflict that pitted American against American in 1861-1865.