Interview by Zach Doleshal

For the fifth installment of our “Making History” series, Zach Doleshal talks to Robert Matthew Gildner, a senior doctoral student in history at the University of Texas at Austin. In the interview, Robert explains why 1952 represented a unique moment for indigenous Bolivians, why previous historians have overlooked this history, and how a trip to Holland inspired him to work on Latin American history.

Robert Matthew Gildner is a Ph.D. candidate in the History Department of The University of Texas at Austin. He is currently writing his dissertation, tentatively titled, “Integrating Bolivia: Revolution, Race, Nation, 1952-1964,” which investigates the cultural politics of national integration in Revolutionary Bolivia to rethink postcolonial nation-state formation in Latin America. Abolishing colonial hierarchies of caste to transform segregated societies into unified republics was at the heart of Latin America’s postcolonial predicament. This predicament was especially acute in Bolivia. Indians constituted seventy percent ofthe population, but remained politically excluded and socially marginalized by a European-decedent, orcreole, minority still a century after Independence. Following the Bolivian Revolution of 1952, a new generation of creole nationalists sought, once and for all, to break with the colonial past. They uprooted the entrenched system of ethnic apartheid that characterized pre-revolutionary society and integrated Indians into a modern nation of their own making. In subsequent years, artists, intellectuals, socialscientists, and indigenous activists worked to transform Bolivia from a segregated, multiethnic society into a unified nation. “Integrating Bolivia” interrogates the dynamic interplay between state and societyas these diverse agents negotiated the terms of indigenous inclusion and the content of national culture.

Although the government granted political citizenship to indigenous Bolivians, it was the cultural politics of revolution that ultimately determined the limits of ethnic inclusion. State officials created a new national culture for the integrated republic, one that venerated Bolivia’s mixed Andean and Hispanic heritage. Historians recast national history as a multiethnic struggle against foreign economic exploitation. Archeologists reconstructed Tiwanaku, identifying in the pre-Hispanic ruins the primordial origins of Bolivian nationhood. Anthropologists studied rural communities, expanding the definitionof cultural patrimony to include indigenous art, music, and dance. Despite the inclusive veneer of this national culture model, it generated novel forms of indigenous exclusion by subsuming ethnic identity to national identity. This ambitious project to decolonize Bolivia thus operated to recolonize it on new terms. Yet, the Revolution did not result in the devastation of indigenous civilization, as dominant historiographical trends contend. Rather, by controlling their cultural representation in the narrow apertures opened by this exclusionary model, indigenous activists successfully bridged political citizenship and ethnic recognition.

Robert’s next project will use a transnational study of Andean mountaineering to examine the relationship between the physical environment, human geography, and nation-state formation in Latin America. During the nineteenth century, political leaders in the fledgling Andean republics of Bolivia, Ecuador,and Peru confronted a similar problem: forging cohesive nation-states in ethnically-fragmented and geologically-diverse territories. As national leaders struggled to overcome the daunting human andphysical geography of the Andes, mountaineering played a critical role in territorial integration, the making of environmental policy, and the definition of geopolitical frontiers. This project examines the adventures and imaginations of British, French, and German mountaineers, their engagement with rural indigenous communities, their reliance on local geographic knowledge, and their connections to liberal political projects across the Andes during a period of capitalist incursion and national consolidation.

Robert Matthew Gildner’s research and teaching focus on the cultural, political, and intellectual history of modern Latin America, with an emphasis on the Andean region. His broader research interests include indigenous politics, historical memory, race/ethnicity, and the construction of knowledge. He has been the recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship, the American Historical Association’s Beveridge Award, and Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowships.

You may also like:

Jessica Wolcott Luther’s interview for Making History, in which she talks about her dissertation on the history of slavery in seventeenth century Barbados.

Christina Salinas’ interview for “Making History,” in which she tells us about her childhood growing up on the Texas-Mexico border.

By Tolga Ozyurtcu

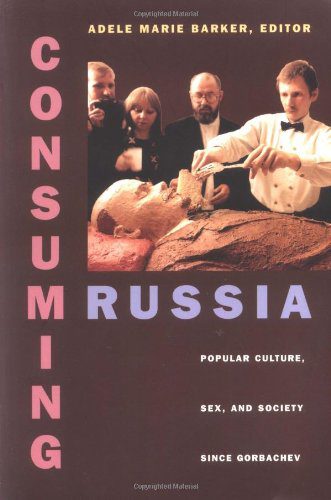

By Tolga Ozyurtcu Caught in the middle of this complex maze of post-Soviet change is popular culture, which “finds itself torn between its own heritage and that of the West, between its revulsion with the past and its nostalgic desire to re-create the markers of it, between the lure of the lowbrow and the pressures to return to the elitist prerevolutionary past.” The quest to find, maintain,and alter cultural identity manifests itself in a variety of ways, which accounts for the large scope of this study.

Caught in the middle of this complex maze of post-Soviet change is popular culture, which “finds itself torn between its own heritage and that of the West, between its revulsion with the past and its nostalgic desire to re-create the markers of it, between the lure of the lowbrow and the pressures to return to the elitist prerevolutionary past.” The quest to find, maintain,and alter cultural identity manifests itself in a variety of ways, which accounts for the large scope of this study.

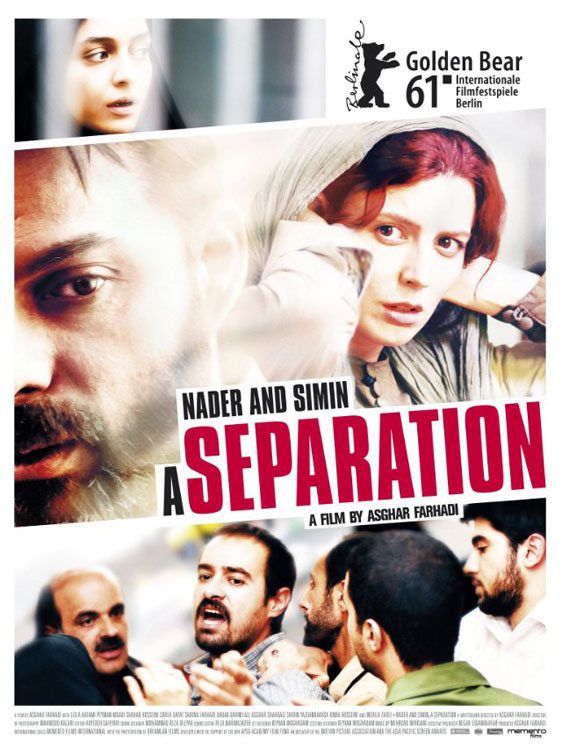

As is indicated by the title, the film focuses on the separation of Nader and Simin, an affluent couple residing in Tehran. Simin wishes to escape Iran’s repressive society and move to Canada, which she believes is a more suitable environment to raise their daughter, Termeh. Nader refuses to leave under the pretext that he must stay in Iran to take care of his elderly father who is suffering from advanced Alzheimer’s disease. Their situation is further complicated by Razieh, a devout Muslim woman from the lower economic class, who is hired to help care for Nader’s father. Numerous financial and personal conflicts pit the well-off Nader and Simin against Razieh and her unemployed, debt-ridden husband, Hojat.

As is indicated by the title, the film focuses on the separation of Nader and Simin, an affluent couple residing in Tehran. Simin wishes to escape Iran’s repressive society and move to Canada, which she believes is a more suitable environment to raise their daughter, Termeh. Nader refuses to leave under the pretext that he must stay in Iran to take care of his elderly father who is suffering from advanced Alzheimer’s disease. Their situation is further complicated by Razieh, a devout Muslim woman from the lower economic class, who is hired to help care for Nader’s father. Numerous financial and personal conflicts pit the well-off Nader and Simin against Razieh and her unemployed, debt-ridden husband, Hojat.

Is empiricism a better guide to historical truth than theory? Is intellectual self-esteem generated internally, or externally, by communal acknowledgment? Taking as its subject the arcane field of Talmudic Studies and the Jerusalem School that persistently practices it, Yosef Sider’s latest film, Footnote, manages to transcend the cultural specificity of his subject matter to embrace a much broader theme. Far from being a film about narrow Jewish, Israeli, or obscure academic subjects, its universal concern is that of fame and recognition, the eternal quest for historical truth, the pursuit of power, and the dynamics of intellectual rivalry.

Is empiricism a better guide to historical truth than theory? Is intellectual self-esteem generated internally, or externally, by communal acknowledgment? Taking as its subject the arcane field of Talmudic Studies and the Jerusalem School that persistently practices it, Yosef Sider’s latest film, Footnote, manages to transcend the cultural specificity of his subject matter to embrace a much broader theme. Far from being a film about narrow Jewish, Israeli, or obscure academic subjects, its universal concern is that of fame and recognition, the eternal quest for historical truth, the pursuit of power, and the dynamics of intellectual rivalry.