by Jacqueline Jones

They met on the boardwalk of Rehoboth Beach, Delaware, on Labor Day of 1941, introduced by mutual friends. She was a self-described ambitious career girl; an English-major graduate of the University of Delaware, she would spend the war years working first in the advertising department of the DuPont Company, and then as the editor of RCA Victor’s company newsletter. He was a mail clerk for DuPont when he enlisted in the Army Air Forces in December of 1941 and began a three-month stint of basic training. Following through on what was apparently a classic case of love at first sight, for four and a half years they carried on a passionate correspondence, seeing each other only during his infrequent furloughs. On one of his last furloughs (in 1944) he proposed, and told her that he wanted to get married within two weeks of coming home, whenever the time came. She said yes.

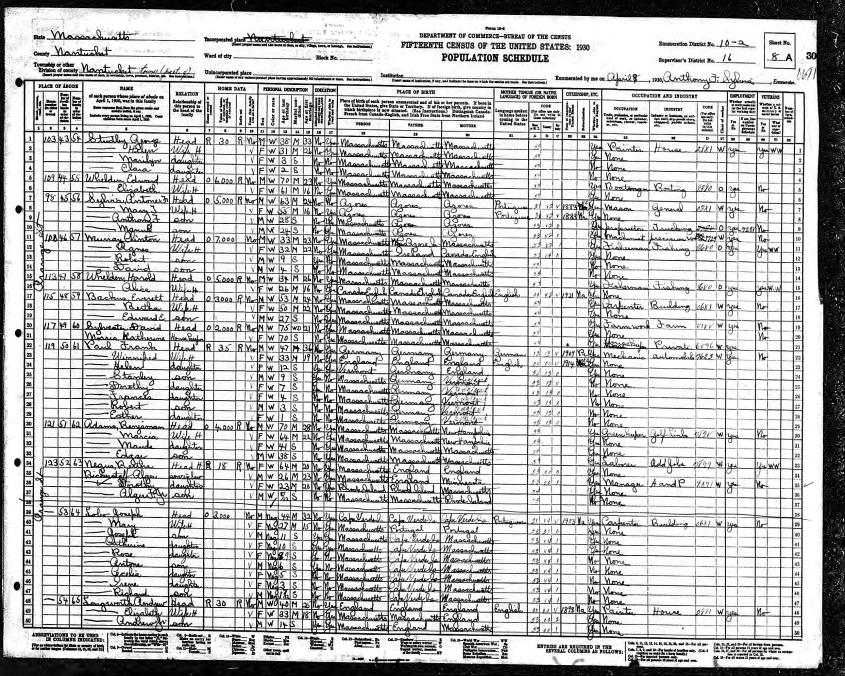

Sylvia Phelps and Albert Jones were born only a few weeks apart, in 1919, and they grew up only a few miles from each other—she in the tiny crossroads of Christiana, Delaware, and he a dozen miles away in Wilmington, the state’s largest city. Perhaps they learned of those connections during their first conversation on the boardwalk. Over time though they would realize that they came from different worlds. She was the somewhat spoiled youngest child of eight, born to sturdy native New Englanders transplanted to Delaware. Her father first worked as a surveyor for coal mining operators and railroad companies. Of necessity the family led a peripatetic existence; the birthplaces of the children chronicled his responsibilities from the Alleghenies to the Blue Ridge Mountains, with the kids born in Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Kentucky, West Virginia, and Virginia. When he settled his family for good in Christiana (in 1924), he prospered from his own sand and gravel business; most of the profits went into paying the college tuition of the children. Sylvia’s parents, finding no Congregational Church in the vicinity of Christiana (or anywhere in Delaware, for that matter), instead joined and became strong supporters of the local Presbyterian Church. The congregation had been founded in 1732, part of the First Great Awakening, and in the twentieth century was still propagating a stern Calvinism based on the doctrines of predestination and original sin.

Albert was the younger son of an alcoholic father who abandoned his wife and two children during the Great Depression. His mother was the daughter of a prominent Wilmington businessman. Although her family’s fortunes declined precipitously in the late nineteenth century, in 1908 her widowed mother managed to send her on an extended grand tour of Europe. Because of a sheltered upbringing, the young woman was not prepared to support the family when her husband left her a “grass widow” in the 1930s. Both Albert and his brother learned to fend for themselves and pick up odd jobs here or there to help support their mother. Moving from one small apartment to another, surrounded by the beautiful dark mahogany furniture their mother had inherited, they lived an irreligious life of genteel poverty. After graduating from high school, Albert started work in a mailroom in a DuPont office building in Wilmington; on his lunch hour and weekends he took flying lessons at the tiny Ballanca airport in nearby New Castle and earned his civilian pilot’s license.

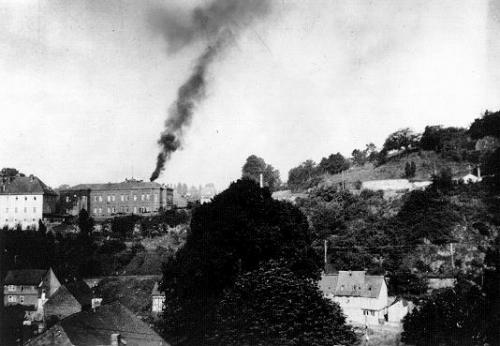

After a variety of wartime assignments that took him to Tennessee, Mississippi, Colorado, North Dakota, and California, he finally arrived at his final destination in the fall of 1944—Twentieth Air Force, 498 Bomber Group, based on the South Pacific island of Saipan. He was a technical sergeant on a B-29 (the so-called “Superfortress”) and served as Central Fire Control (“Top Gun”) on the top of the plane. Through an intercom he radioed the tail gunners below and directed their machine-gun fire to oncoming targets in the air. In the summer of 1945, he and the other crew members successfully completed their quota of thirty bombing missions, mostly raids over Japanese cities.

A published history of the Twentieth Air Force supplied the numbers that represented so much death and destruction inflicted on Japan those last months of the war—65 principal cities obliterated or severely damaged; 602 major war factories destroyed; 1,250,000 tons of shipping sunk by aerial mines; 83 percent of oil refinery production and 75 percent of aircraft engine production destroyed; more than 2 million homes leveled; 330,000 men, women, and children killed and another half million wounded; 8,500,000 people rendered homeless and 21,000,000 displaced.

Albert, my father, was wounded, though not seriously, on one of his missions. Other facts and figures are obscure: How many planes he saw explode and spiral downwards, out of the sky; how many comrades he lost; how many nightmares he endured; how many times he longed for my mother and home. For her part, my mother Sylvia tried to keep busy with work, but could not tamp down the constant anxiety she felt. A devout Presbyterian, she went over in her mind the questions that religion could not seem to answer: Why would an all-powerful deity make this sensitive young man whom she loved so much the instrument of so much pain? How could he, a good person, live with the fact that he had his comrades had killed so many people—so many innocent civilians—whom they had never known or seen? Not until after her death (in 2008) did my brothers and I discover a poem she had written sometime in the summer of 1945, trying to reconcile her faith in an omnipotent God with her fears for my father’s safety—and perhaps for his soul.

For a Gunner

Lord, Thy Glory fills the Heaven—

Will he ever find you there,

In his plan on war-bent mission

Speeding death bombs through the air?

What have You to do with bombers,

Lord, the God of peace and love?

Will you speed him on his journey?

Guide, protect him from above?

Lord, he doesn’t like the killing;

His was not the choice to fight…

It’s so hard to feel Your mercy

In the tense blackout of night.

Lord, Thy Glory fills the Heaven—

Let him glimpse You there on high;

Calm his fear and hate and turmoil

In the vast peace of Your sky.

My father was mustered out of the service on September 1, 1945, and my parents married two weeks later, on September 15. Theirs was a happy and an enduring marriage, severed only by the death of my father a few months shy of their fiftieth wedding anniversary in 1995.

Photo Credits:

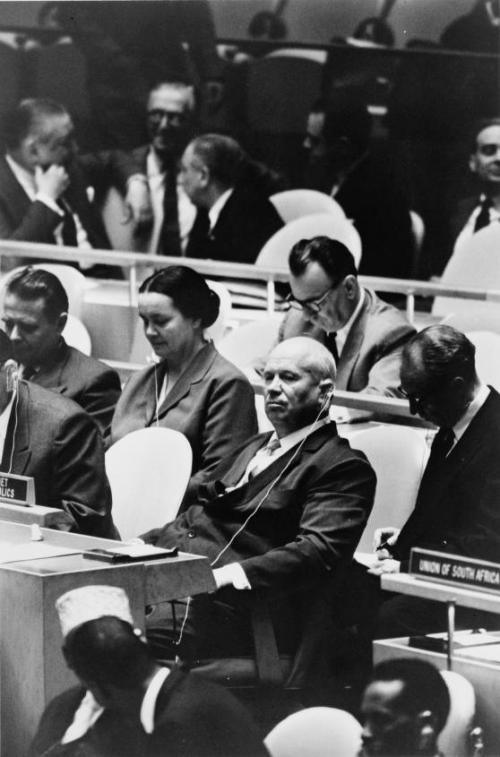

Photographs of Sylvia Phelps and Albert Jones, the author’s parents