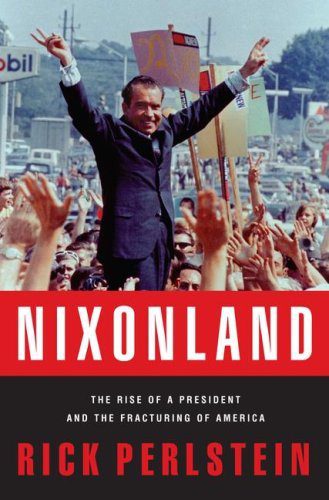

Rick Perlstein traces the antecedents of contemporary American politics to the period 1965-1972, presenting Richard Nixon as a central figure in creating a foundation for today’s bitter partisanship. Perlstein builds his story around the 1966, 1968, 1970, and 1972 elections, where Nixon, “the brilliant and tormented man struggling to forge a public language that promised mastery of the strange new angers, anxieties, and resentments wracking the nation in the 1960s,” acted as a critical participant. The author argues that during this time period, Americans intensely divided into two general groups, “each equally convinced of its own righteousness, each equally convinced the other group was defined by its evil.” Richard Nixon exploited the fears and rages of those Americans who resented elites and activists, further tearing apart the United States into warring political factions and establishing what Perlstein terms “Nixonland.” The nation of Nixonland persists today in America’s polarized electorate, which remains incapable of escaping the feuds initiated in the 1960s.

The author contemplates why Americans elected two presidents from different parties in landslides over a matter of eight years (Democrat Lyndon Johnson in 1964 and Republican Richard Nixon in 1972). He concludes that as Democratic liberalism collapsed under the weight of intense unrest at home and violence in Vietnam during the 1960s, Nixon sought to build a new political coalition among Americans who loathed the chaos permeating their society. Perlstein argues that Nixon particularly courted white southerners and northern working-class ethnics who resented the burgeoning counterculture, antiwar protestors, and Democratic embracement of civil rights. Yet as Nixon demonized his detractors and successfully captured the presidency in 1968, Democratic victories in the 1970 midterm elections and his increasing paranoia led him to conclude that his failure to be re-elected in 1972 would lead to the downfall of the United States, with its governance placed again in the hands of liberals now all the more influenced by civil rights activists, antiwar protestors, and rebellious youth. These obsessions caused him to resort to any means necessary to win a second term, leading to his own ruin in the Watergate scandal.

The author contemplates why Americans elected two presidents from different parties in landslides over a matter of eight years (Democrat Lyndon Johnson in 1964 and Republican Richard Nixon in 1972). He concludes that as Democratic liberalism collapsed under the weight of intense unrest at home and violence in Vietnam during the 1960s, Nixon sought to build a new political coalition among Americans who loathed the chaos permeating their society. Perlstein argues that Nixon particularly courted white southerners and northern working-class ethnics who resented the burgeoning counterculture, antiwar protestors, and Democratic embracement of civil rights. Yet as Nixon demonized his detractors and successfully captured the presidency in 1968, Democratic victories in the 1970 midterm elections and his increasing paranoia led him to conclude that his failure to be re-elected in 1972 would lead to the downfall of the United States, with its governance placed again in the hands of liberals now all the more influenced by civil rights activists, antiwar protestors, and rebellious youth. These obsessions caused him to resort to any means necessary to win a second term, leading to his own ruin in the Watergate scandal.

Nixonland is a magnificent work presenting a detailed political, social, cultural, and economic history of the United States during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Perlstein illustrates how the United States of today, especially in its acrimonious politics, owes much of its legacy to this tumultuous era. Perlstein concludes: “Both populations—to speak in ideal types—are equally, essentially, tragically American. And both have learned to consider the other not quite American at all. The argument over Richard Nixon, pro and con, gave us the language for this war.”

By George Christian

By George Christian

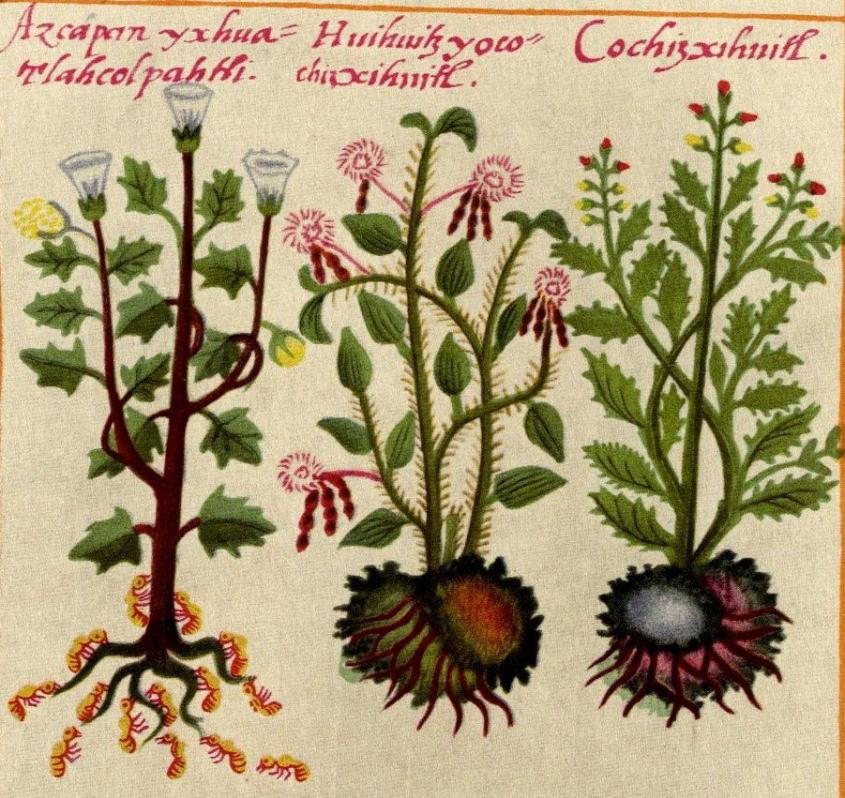

The Codice de la Cruz-Badiano is an example of the encounter of between writing systems, and thus of systems of knowledge, with multiple swings from the pictographic-glyphic tradition to the alphabetical. The illustrations are by no means subordinated to the writing. Visual evidence and linguistic analysis of Náhuatl offer ways of approaching the complexities of cultural forms and to provide information about natural history that was not present in the Latin texts.

The Codice de la Cruz-Badiano is an example of the encounter of between writing systems, and thus of systems of knowledge, with multiple swings from the pictographic-glyphic tradition to the alphabetical. The illustrations are by no means subordinated to the writing. Visual evidence and linguistic analysis of Náhuatl offer ways of approaching the complexities of cultural forms and to provide information about natural history that was not present in the Latin texts.

by

by

In this book, Bayat successfully dismantles the presumptions that constitute this discourse, by stating in the beginning that “the question is not whether Islam is or is not compatible with democracy, or by extension, modernity, but rather under what conditions Muslims can make them compatible.” In order to answer this question Making Islam Democratic closely examines the different trajectories of two countries with similar socio-religious backgrounds: Iran and Egypt. Specifically Bayat asks why Iran produced an Islamic revolution, while Egypt developed only an Islamic Movement.

In this book, Bayat successfully dismantles the presumptions that constitute this discourse, by stating in the beginning that “the question is not whether Islam is or is not compatible with democracy, or by extension, modernity, but rather under what conditions Muslims can make them compatible.” In order to answer this question Making Islam Democratic closely examines the different trajectories of two countries with similar socio-religious backgrounds: Iran and Egypt. Specifically Bayat asks why Iran produced an Islamic revolution, while Egypt developed only an Islamic Movement. Rejecting the oft-repeated assertion that U.S. foreign policymakers were ignorant or inattentive to the realities of power in the Soviet Union and the complexities of Third World nationalism, Leffler argues that cold warriors on both sides of the iron curtain were in fact keenly aware of the liabilities inherent in the zero-sum approach to international politics. Benefiting from access to multiple archives and a clear command of the secondary historical literature, Leffler has crafted a persuasive and thoroughly documented analysis that recasts the Cold War as not simply a political, economic, or military confrontation, but a battle “for the soul of mankind.” In doing so, he has transcended the scholarly debate over whether economic, structural, or ideological factors were more influential in determining the course of Cold War history.

Rejecting the oft-repeated assertion that U.S. foreign policymakers were ignorant or inattentive to the realities of power in the Soviet Union and the complexities of Third World nationalism, Leffler argues that cold warriors on both sides of the iron curtain were in fact keenly aware of the liabilities inherent in the zero-sum approach to international politics. Benefiting from access to multiple archives and a clear command of the secondary historical literature, Leffler has crafted a persuasive and thoroughly documented analysis that recasts the Cold War as not simply a political, economic, or military confrontation, but a battle “for the soul of mankind.” In doing so, he has transcended the scholarly debate over whether economic, structural, or ideological factors were more influential in determining the course of Cold War history.