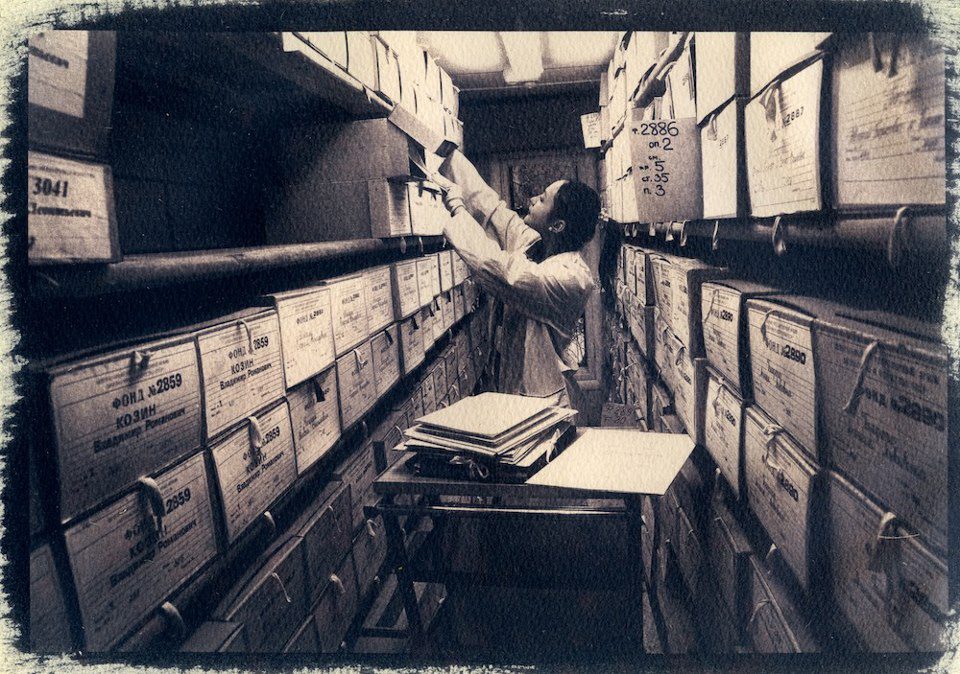

Each fall I take my first-year seminar students to one of UT’s archives. They’re pretty sure this will be the most boring class ever. The archivists and I talk a bit about the people whose things are stored in the cardboard cartons and plastic containers piled up on the table, lowering their expectations even further. But then we open the boxes. Someone pulls out a local journalist’s datebook and starts flipping through the weeks of alternating banal and extraordinary events. And someone else finds a poet’s meticulously detailed correspondence with her lawyer. Another student opens a container to find an abstract sculptor’s childhood sketchbook that’s filled with ornate fantasy drawings. Skeptical silence gives way to animated conversation and suddenly everyone is walking around sharing their treasures with their friends. It never fails. Even if you don’t love history, there is nothing like original documents for connecting us to the past.

Russian State Archive of Literature and Art

Historians won’t be giving up their visits to archives or their days picking notebooks and letters out of boxes any time soon. But the path to those boxes has changed dramatically as institutions and history enthusiasts have been digitalizing and posting their treasures online. Virtual documents are not the same as little leather bound notebooks and papers signed by presidents, but they are the next best thing and now you can find a lot of them while sitting at home on your couch. Scholars and graduate students can do substantial research at their desks and undergraduates can do much more sophisticated original research using online documents collections. And history enthusiasts can create personal archives for every niche interest just by setting up a Tumblr or Pinterest account.

Like blogging, the world of online collections is too large to cover fully here –- or probably anywhere these days. I’ve picked a few representative collections to give you a sense of what’s out there.

But first, the big news in online collections is the launch this week of the Digital Public Library of America.* The DPLA, in the words of its founding director, Dan Cohen, a leading digital history pioneer, will be

connecting the riches of America’s libraries, archives, and museums so that the public can access all of those collections in one place; providing a platform, with an API [application programming interface] for others to build creative and transformative applications upon; and advocating strongly for a public option for reading and research in the twenty-first century. The DPLA will in no way replace the thousands of public libraries that are at the heart of so many communities across this country, but instead will extend their commitment to the public sphere, and provide them with an extraordinary digital attic and the technical infrastructure and services to deliver local cultural heritage materials everywhere in the nation and the world.

The DPLA is poised to become the main hub in the universe of online collections. The US National Archives has already “donated” 1.2 million of its objects and documents to the DPLA and other public institutions are lining up to make their collections available there. This is one to watch.

In the meantime, the growing number of online collections fall roughly into three categories: big and varied collections of documents, photographs, and other objects, smaller curated collections focused on a specific topic, or blog-like publications of images on a single topic.

In the first category, one of the earliest and best major online collections is just celebrating its tenth anniversary. The Proceedings of the Old Bailey, London’s Criminal Court, 1674-1913, with documents on almost 200,000 trials and biographical information on 2500 individuals, is the largest collection of “texts detailing the lives of non-elite people ever published.” The individual documents are available as typed text and as scanned facsimile. In addition to the documents, background essays offer the historical context for understanding the court proceedings and the place of the court in London social history. A variety of search techniques are offered (and very clearly explained), some using quite complex digital technologies. The site also offers essays and smaller, curated collections on specific topics, like Black Communities in London or Gender in the Proceedings that require no prior knowledge and can be of interest to general readers as well as specialists. These features make The Old Bailey website a model of organization and accessibility.

The Portal to Texas History is another huge collection with close to 300,000 items, including full runs of rare local newspapers, photographs, books, and maps. The Portal’s education pages, linked to the state history standards for 4th and 7th grade, are especially good. Individual topics (The Battle of San Jacinto) come complete with primary sources, visual and text, instructions on reading sources, and classroom activities. Sets of primary sources on broader topics (Native Americans in Tejas, Cowboy Culture, Civil Rights, and individuals including Sam Houston and Quanah Parker), are a good place to start a research project, but they’re fun to read for anyone interested in history, especially local history.

Smaller, curated collections can present a wide variety of sources on a single topic. My favorite recent discovery is Women’s Worlds in Qajar Iran (1786-1925) at the Harvard website. Like a lot of these sites, WWQI can be used for research or it can be browsed for fun: texts of letters, poetry, essays, diaries; legal documents on wedding contracts and dowry agreements, wills and finances; photographs and works of art; everyday objects and oral histories on a topic that was completely new to me, can all now be enjoyed by anyone with a computer.

Another thematically focused collection is the Digital Archive from the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, which makes available declassified government documents from all over the world. The documents are organized by topics like Sino-Soviet Relations (242 documents), The Berlin Wall (28 documents), or Intelligence Operations in the Cold War (111 documents). Want to read up on the history of North Korean foreign policy? The home page has Featured Collections, which today include what they call North Korean Military Adventurism (72 documents dating back to 1967). We often have students who want to write an honors thesis or research paper on an international topic but don’t know the languages well enough to do research; sites like these make international research projects possible. World History Matters is another George Mason site that offers links to online collections, both specific, such as Women in World History, and general, Finding World History, which includes an annotated list of sites organized by world region and time period.

These smaller curated collections allow readers to see connections between various media or authors or historical actors. They can give a newcomer to the field a broad familiarity with the kinds of documents, objects, opinions, experiences, and forms of communication produced by a discrete group. They differ from the big collections like The Old Bailey or the Texas Portal because their pages have been carefully selected from an even larger pool of raw documents. None of these sites or collections claims to be definitive; just the opposite. They all offer links to other collections, or lists of further reading for placing their materials in historical context.

Another form of curated documents can be found on websites that publish clusters of documents organized primarily for classroom use. The National Humanities Center runs a site, America in Class, that is also organized for teachers but is fun to explore on its own. Sources (including visual images and sound files) and classroom guides, as well as links to many other online collections, cover US History from 1492 through the 1920s. I found the collections on the Revolution and on African American history especially interesting. Similar US History collections that select and organize documents with teaching in mind include History Matters from George Mason University, Digital History from the University of Houston, and Primary Sources at the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. These are similar to documents collections published in books, except that they often include audio or visual clips and they can take advantage of the web’s primary function and provide links to related material. The reading experience is enhanced by these possibilities for expansion.

Internet technology has been especially useful for any libraries with collections of photographs and other visual images to make their collections available. The Library of Congress and the New York Public Library have enormous image collections. The NYPL collection, for example, is divided into topical collections, the richness of which is hard to capture. Just scratching the surface these include: Russia and Eastern Europe in Rare Photographs, cars, cigarette cards, nature, New York City, the Middle East, more than 2000 Medieval and Renaissance illuminated manuscripts are a few of the topics listed in their index. Wikimedia Commons, the visual branch of Wikipedia, contains some 16 million images that are all in the public domain. More specialized collections are becoming available as well. On a smaller scale, the Winterton Collection of East African Photographs is a stunning collection of over 7000 photos. And like most of the collections that come from educational institutions, this one comes with a page devoted to Winterton in the Classroom that provides historical analysis (timeline, essays, links to other historical sources) and context for thinking about the images.

The context is what’s missing from many popular history collections online. The Tumblr Spotlight: History page links to blog after blog of related but skimpily identified images. One of my favorites is called Turn of the Century, which describes itself as “everything strange and beautiful from 1850s-1920s.” I also like “My Daguerreotype Boyfriend,” a collection of handsome men in early photographs.

As a professional historian and public history promoter, I have mixed feelings about these sites. They’re fun and very popular and I enjoy the time I spend looking at them, but they exist only to be collected, quickly glimpsed, “liked,” maybe “shared,” and soon forgotten. Half the time, this doesn’t bother me at all: people have been collecting random objects and displaying them for all of recorded history. If nothing else, these sites show us that there’s a real public interest in history; these uncontextualized collections may even represent the dominant public interest in history. And are they that different from the Wilson Center’s selected collections or the images posted by The Library of Congress? The historian in me wants more information about provenance and historical context, but lacking that, there is still a visceral pleasure in the looking, which is worth cultivating, and may inspire the kinds of questions that lead people to seek more.

Optimism about the desire to both look at and learn more about such images comes from an unlikely place: the enormous link aggregator, Reddit, which has pages of links on every topic under sun. The aptly named HistoryPorn, is a subreddit for posting pictures of historical events. It’s not that different from a Tumblr blog, except that instead of being organized chronologically, the image links that appear at the top of the page are the ones that have received the most votes from other subreddit readers. The top link today as I write is “Burst of Joy,” a 1973 photo of ecstatic family members greeting their father who has been in a POW camp in North Vietnam. But there are also dozens of subreddits on major historical topics. The “History of Ideas” subreddit, for example, leads off with podcasts from Oxford on Shakespeare, a review of a book about Machiavelli, Hobbes, and Rousseau, and a lecture by Stanford professor Paul Robinson on Darwin. There is even a subreddit for recommended books in history and a page devoted to links to other history websites and resources on line.

The history pages on Reddit lack consistency but offer a way for history lovers to talk to each other, ask questions, and share their discoveries. HistoryPorn readers can look-and-run if they want, but if they’re curious, they can google “Burst of Joy,” and find themselves at Iconic Photos or Mechanical Icon or the Newseum to read or watch a video or listen to the photographer talk about the Pulitzer Prize winning photograph and its surprising back story. And then if one wants more, anyone can go straight to the website of the US National Archives to find original documents on photojournalism during the Vietnam War. These virtual images and texts can’t replicate the pleasure of holding original documents in your hands, but they make up for that by being so easily accessible and searchable, by being so seamlessly linked, and in many cases, by being so pleasurable to see.

*

Stay tuned for Part 3: Digital History For Real.

You might also enjoy:

Digital History: A Primer (Part 1).

Daniel J. Cohen and Roy Rosenzweig, Digital History: A Guide to Gathering, Preserving, and Presenting the Past on the Web

Blog post about whether the DPLA will define what counts in Digital Humanities

*The Launch of the DPLA was postponed after the bombing at the Boston Marathon.

Reflecting on his motives for joining the Royal Welch Fusiliers at the outbreak of the First World War, Robert Graves wrote: “I thought that it might last just long enough to delay my going to Oxford in October, which I dreaded.” So began a five year pause in Graves’ life, in which the main action of his autobiography unfolds. In Good-Bye to All That, Graves powerfully explores the horrors of the First World War, while also providing a compelling look at the inner workings of British society.

Reflecting on his motives for joining the Royal Welch Fusiliers at the outbreak of the First World War, Robert Graves wrote: “I thought that it might last just long enough to delay my going to Oxford in October, which I dreaded.” So began a five year pause in Graves’ life, in which the main action of his autobiography unfolds. In Good-Bye to All That, Graves powerfully explores the horrors of the First World War, while also providing a compelling look at the inner workings of British society. English soldiers in the trenches at Nieuport Bains, Belgium, 1917. The sergeant in the foreground is watching the German line through a periscope fixed on his bayonet. (Image courtesy of the United Kingdom Government)

English soldiers in the trenches at Nieuport Bains, Belgium, 1917. The sergeant in the foreground is watching the German line through a periscope fixed on his bayonet. (Image courtesy of the United Kingdom Government)

How important are these changes? At this year’s annual convention of the American Historical Association,

How important are these changes? At this year’s annual convention of the American Historical Association,