This month on Not Even Past we are celebrating the accomplishments of seventeen students who completed their doctoral dissertations and received their PhDs in History in 2018-2019. Above you see some of them pictured. Below you will find each of their names and the title of their dissertations.

Many of these students were also contributors to Not Even Past throughout their time here, developing their skills as public historians alongside their training as a academics. Here we offer a comprehensive index to all our new PhDs’ publications on Not Even Past. Congratulations to all!

![]()

Ahmad Tawfek Agbaria

Dissertation: The Return of the Turath: Arab Rationalist Association 1959-2000

Ordinary Egyptians: Creating the Modern Nation through Popular Culture by Ziad Fahmy (2011)

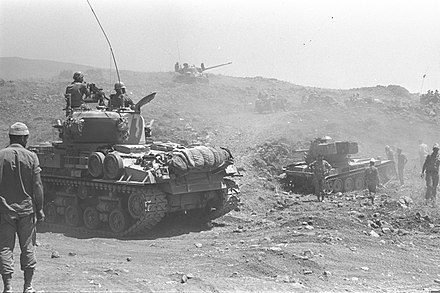

Israeli tanks advancing on the Golan Heights. June 1967 (via Wikipedia)

Christopher Babits

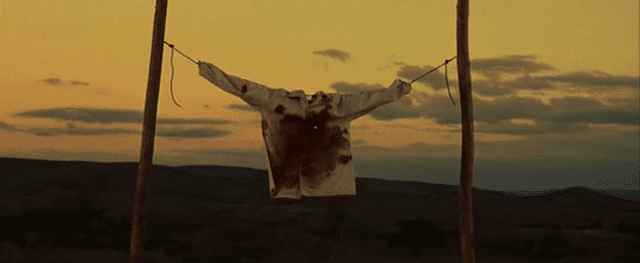

Dissertation: To Cure a Sinful Nation: Conversion Therapy in the United States

The Miseducation of Cameron Post (Dir: Desiree Akhavan, 2018)

Digital Teaching: A Mid-Semester Timeline

The Blemished Archive: How Documents Get Saved

Age of Fracture by Daniel T. Rodgers (2011)

Nature Boy, 30 for 30 (Dir: Rory Karpf, 2017)

Doing History in the Modern U.S. Survey: Teaching with and Analyzing Academic Articles

Finding Hitler (in All the Wrong Places?)

The Rise of Liberal Religion by Matthew Hedstrom (2013)

Another Perspective on the Texas Textbook Controversy

Bradley Joseph Dixon

Dissertation: Republic of Indians: Law, Politics, and Empire in the North American Southeast, 1539-1830

Facing North from Inca Country: Entanglement, Hybridity, and Rewriting Atlantic History

Map of Virginia, discovered and as described by Captain John Smith, 1606; engraved by William Hole (Via Wikimedia commons)

Luritta DuBois

Dissertation: United in Our Diversity: The Reproductive Healthcare Movement, 1960-2000

Historical Perspectives on Marshall (dir. Reginal Hudlin, 2017)

UT Gender Symposium: Women’s Bodies and Political Agendas

Dennis Fisher

Dissertation: To Not Sell One Perch: Algonquin Politics and Culture at Kitigan Zibi During the Twentieth Century

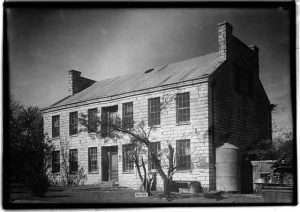

The Many Histories of South Austin: The Old Sneed Mansion

A 1936 photograph of the Sneed House taken by the Historic American Buildings Survey (via Library of Congress)

Kristie Flannery

Dissertation: The Impossible Colony: Piracy, the Philippines, and Spain’s Asian Empire

A New History Journal Produced by Students

#changethedate: Australia’s Holiday Controversy

Acapulco-Manila: The Galleon, Asia and Latin America, 1565-1815

Notes from The Field: The Pope in Manila

Outlaws of the Atlantic by Marcus Rediker (2014)

Sixteen Months in a Leaky Boat

True History of the Kelly Gang by Peter Carey (2001)

Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War by Tony Horwitz (1999)

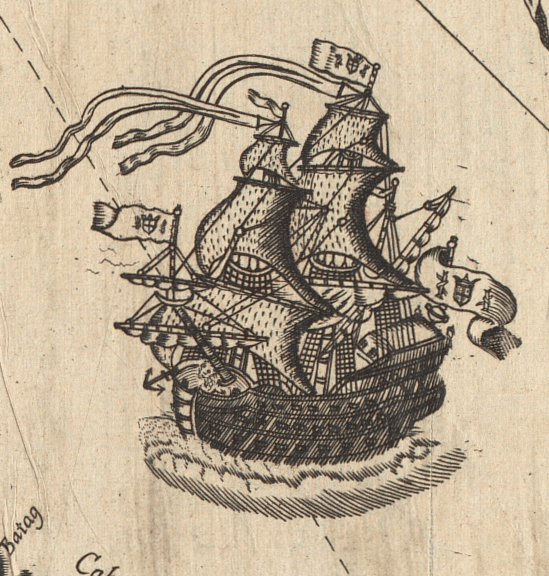

Pedro Murillo Velarde and Nicolas de la Cruz Bagay. Mapa de las yslas Philipinas (1744) (Detail: Benson Latin America Collection, UT Austin)

Travis Michael Gray

Dissertation: Amid the Ruins: The Reconstruction of Smolensk Oblast, 1943-1953

Every Day Stalinism, by Sheila Fitzpatrick (2000)

Stalin’s Genocides by Norman Naimark (2011)

Soviets fighting during World War II (via wiki commons)

William Kramer

Dissertation: Faith, Heresy and Rebellion: Resisting the Henrician Reformation in Ireland, 1530-1540

Henry VIII, Elizabeth I, and Edward VI (via Art Institute of Chicago)

John Lisle

Dissertation: Science and Espionage: How the State Department and the CIA Deployed American Scientists during the Cold War

This New Ocean: The Story of the First Space Age by William Burrows (1998)

James Martin

Dissertation: In Search of the Nixon Doctrine on Latin America: Levers of Influence and Resistance in Hemispheric Relations

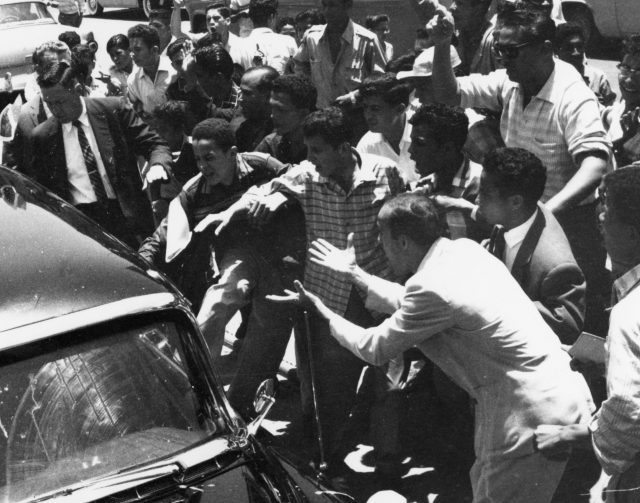

Vice President Richard Nixon’s motorcade drives through Caracas, Venezuela and is attacked by demonstrators, May 1958 (National Archives via Wikipedia)

Kazushi Minami

Dissertation: Rebuilding the Special Relationship: People’s Diplomacy and U.S.-Chinese Relations in the Cold War

Peeping Through the Bamboo Curtain: Archives in the People’s Republic of China

Cold War Crucible: The Korean Conflict and the Postwar World by Hajimu Masuda (2015)

Past and Present in Modern China

Historical Perspectives on Hayao Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises (2013)

Elizabeth O’Brien

Dissertation: Intimate Interventions: The Cultural Politics of Reproductive Surgery in Mexico, 1790-1940

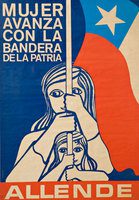

Gendered Compromises: Political Culture and the State in Chile, 1920-1950 by Karin Rosemblatt

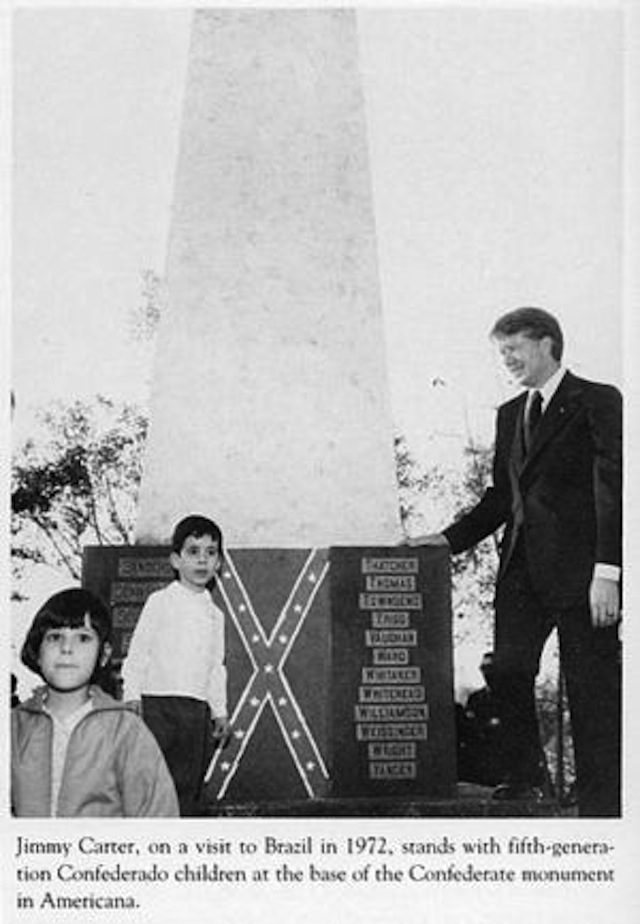

Nakia Parker

Dissertation: Trails of Tears and Freedom: Black Life in Indian Slave Country,1830-1866

Popular Culture in the Classroom

The First Texans: An Exhibit in Jester Hall

Confederados: The Texans of Brazil

Christopher Rose

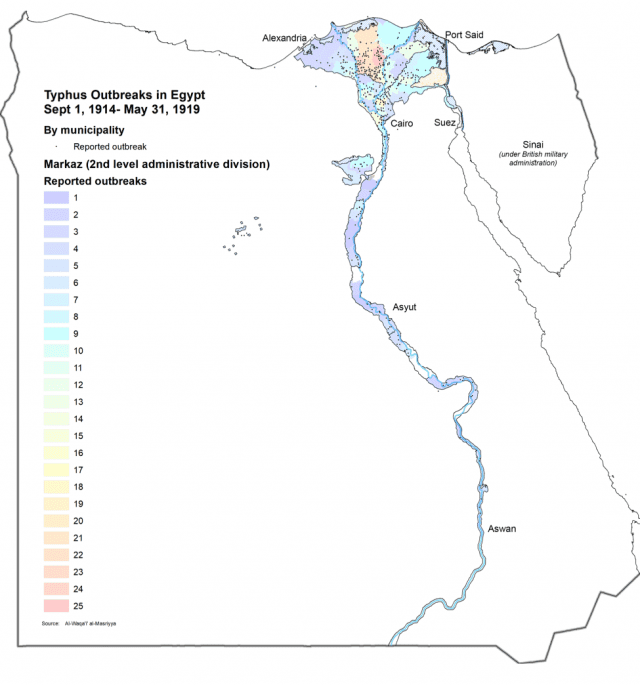

Dissertation: On the Home Front: Food, Medicine, and Disease in WWI Egypt

Mapping & Microbes: The New Archive (No. 22)

Searching for Armenian Children in Turkey: Work Series on Migration, Exile, and Displacement

Industrial Sexuality: Gender in a Small Town in Egypt

Texas is Adopting New History Textbooks: Maybe They Should Be Historically Accurate

The Ottoman Age of Exploration by Giancarlo Casale (2010)

What’s Missing from ‘Argo’ (2012)

Chris is also the co-founder and main force behind our podcast, 15 Minute History, where he has done many of our interviews.

Edward Flavian Shore

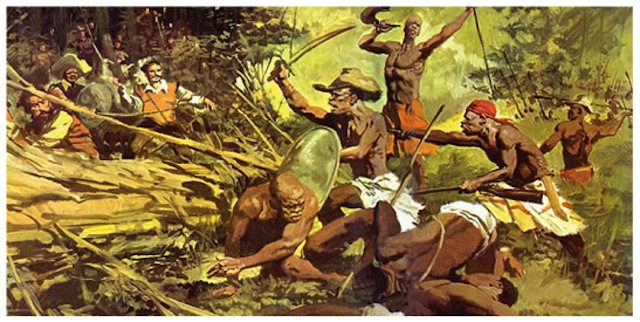

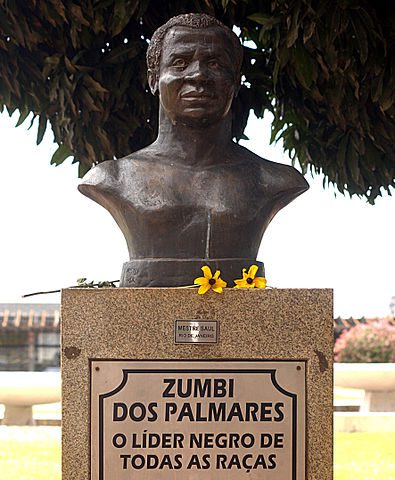

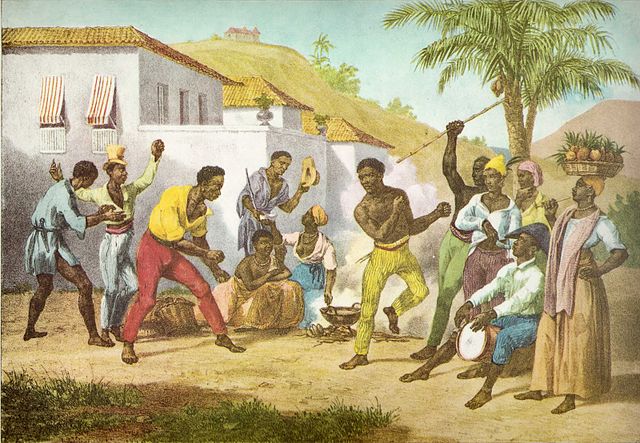

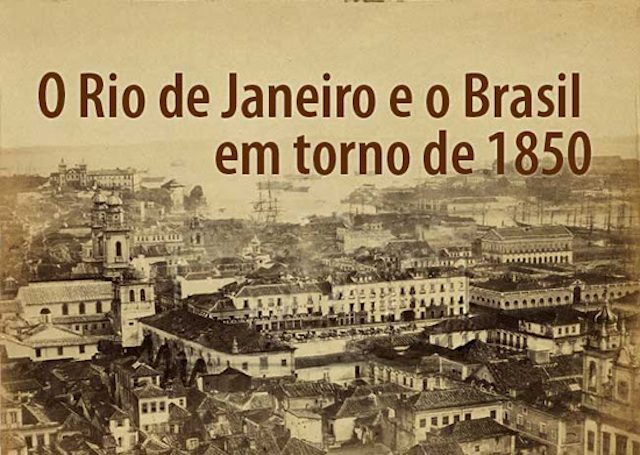

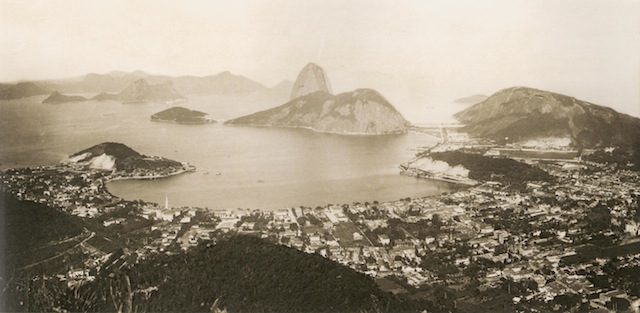

Dissertation: Avenger of Zumbi: The Nature of Fugitive Slave Communities and Their Descendants in Brazil

History and Advocacy: Brazil and Turmoil

Sanctuary Austin: 1980s and Today

Beyonce as Historian: Black Power at the DPLA

Remembering Willie “El Diablo” Wells and Baseball’s Negro League

The Public Historian: Giving it Back

The Quilombo Activist’s Archives and Post-Custodial Preservation, Part II

The Quilombo Activist’s Archives and Post-Custodial Preservation, Part I

An Anticipated Tragedy: Reflections on Brazil’s National Museum

The Public Historian: Quilombola Seeds

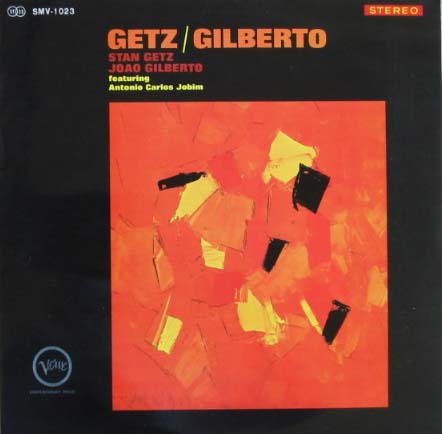

Getz/Gilverto Fifty Years Later: A Retrospective

Por Ahora: The Legacy of Hugo Chávez Frías

The Cuban Connection by Eduardo Saénz Rovner (2008)

Che: A Revolutionary Life by Jon Lee Anderson

Eyal Weinberg

Dissertation: Tending to the Body Politic: Doctors, Military Repression, and Transitional Justice in Brazil (1961-1988)

Our History Mixtape: Embracing Music in the Classroom

Ex Cathedra: Stories by Machado de Assis: Bilingual edition (2014)

The Works Progress Administration’s music project employed musicians as instrumentalists, singers, concert performers, and music teachers during the Great Depression (via Library of Congress)

Zhaojin Zeng

Dissertation: Nourishing Shanxi: Indigenous Entrepreneurship, Regional Industry, and the Transformation of a Chinese Hinterland Economy, 1907-2004

Capitalism with Chinese Characteristics: Entrepreneurship and the State by Yansheng Huang (2008)

Cantonese bazaar during Chinese New Year at the Grant Avenue, San Francisco, circa 1914 (via Wikipedia)

Pictured in photo: Dr. John Lisle, Prof Daina Berry, Dr. William Kramer, Dr. Nakia Parker, Prof. Ann Twinam, Dr. Christopher Rose, Dr. Elizabeth O’Brien, Dr. Eyal Weinberg.