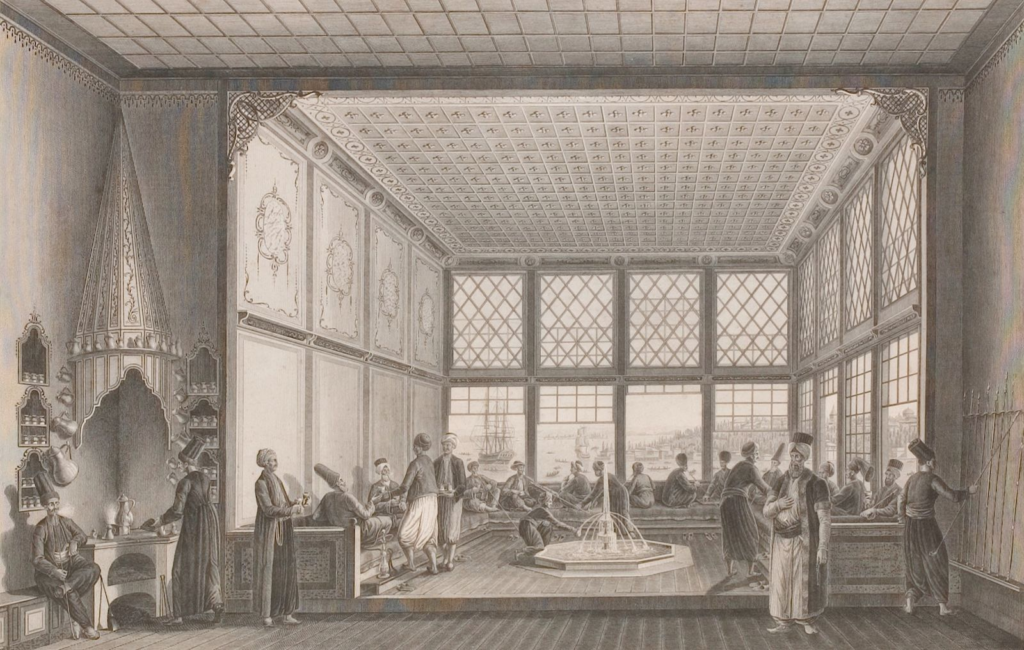

What is the ‘Enlightenment’? This is a question that has occupied scholars ever since Kant. But historians no longer focus on great white heroes to provide answers. Yet sociologies of knowledge on the ‘Enlightenment’ continue to render the experiences of the north Atlantic normative. These sociologies tell us that the Enlightenment was not about secular radicals using reason to topple the religious and feudal hierarchies of the ancien régime. It was rather about new forms of sociability triggered by revolutions in print and communication that made a republic of letters and a public sphere of coffee shops and periodicals possible. These new bottom-up institutions, as this narrative has it, allowed for new mercantile middle classes to challenge top-down hierarchies of knowledge and politics.

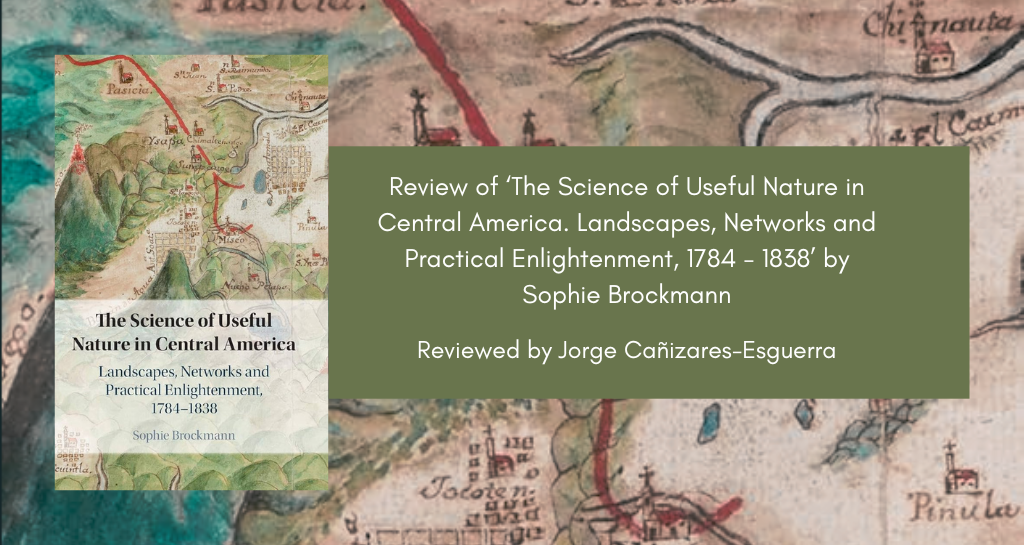

As common as it is, this model, however, does not fit most global experiences of the ‘Enlightenment’. In a 2020 study, Brockmann investigates the case of turn-of-nineteenth-century Central America to challenge the norm.

Brockmann brings to life a coterie of religious and lay Spanish American bureaucracies that for some forty years were obsessed with ‘bringing light’ onto everyone, from Chiapas to Costa Rica. Engineers, military officers, architects, bishops, field justices, priests, high court judges, doctors, lawyers, landowners, among many others, organized themselves in patriotic societies to produce a newspaper to network and to circulate only ‘useful’ knowledge aimed at transforming local landscapes. One could argue that this community was a ‘public sphere’ created by print culture. Yet Brockmann demonstrates that these were colonial bureaucracies who were prompted by top-down crown initiatives to create patriotic societies and newspapers to communicate and innovate. Moreover, in the kingdom of Guatemala, landscapes were constantly threatened by earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, locust, anthrax, typhus, smallpox, and falling prices of indigo, the main staple.

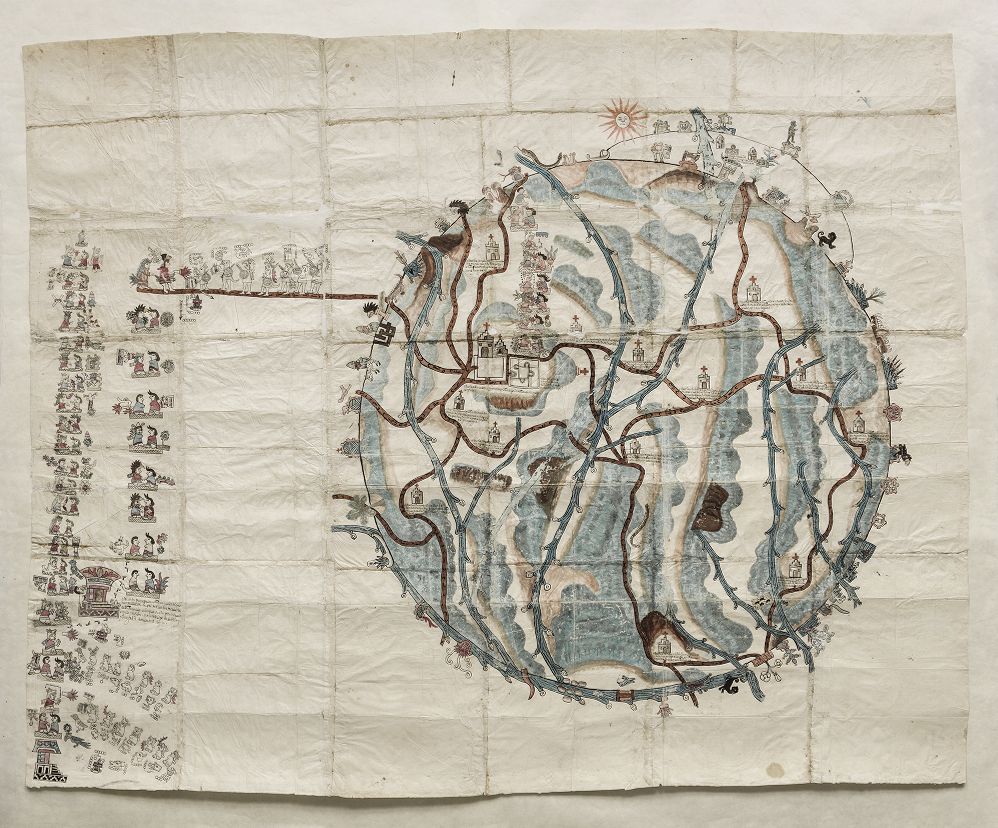

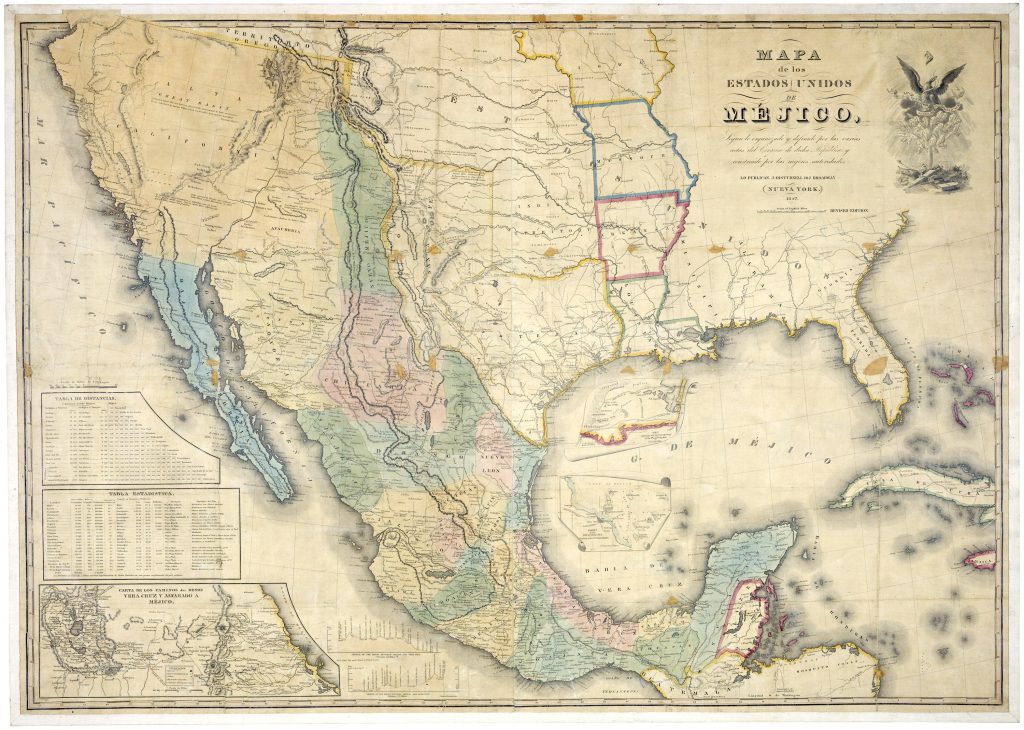

How to produce indigo, flax, silk? How to avoid tropical miasmas caused by rotten, humid tropical trees? How to reorganize settlement patterns and prompt populations to settle in both Pacific and Atlantic new ports? How to reengineer mercantile circuits opening new roads? These bureaucracies had long drafted reports on local demography, production, roads, landscapes. Bishops, field justices, court magistrates, and municipal authorities of the various administrative units of the kingdom of Guatemala, a territory that covered dozens of cities and towns from southern Mexico to northern Panama, had long crisscrossed the lands and produced paperwork to mete out justice and enact reform.

They embodied the Enlightenment as much as the late eighteenth-century engineers and judges Brockmann has chosen to study. All lay and religious colonial bureaucracies, Habsburg and Bourbon, used archives to develop a sense of the changing nature of territories bewildered by contingency, disaster, and environmental change. Guatemala’s capital, alone, was twice obliterated, relocated, and rebuilt after eruptions and earthquakes. Theirs was an enlightenment of ever-changing landscapes and bureaucratic archives.

Brockmann demonstrates that these bureaucratic networks held together by new patriotic societies and print embraced new languages of utility and political economy but not necessarily new practices of paperwork and administering knowledge and land reform. Transfixed by the idea of Enlightenment progress and innovation, Brockmann artificially separates these late eighteenth-century bureaucracies from their robust predecessors, neglecting some two hundred years of bureaucratic audits, reports, and endless horizontal and vertical communication with peers, and local and peninsular authorities.

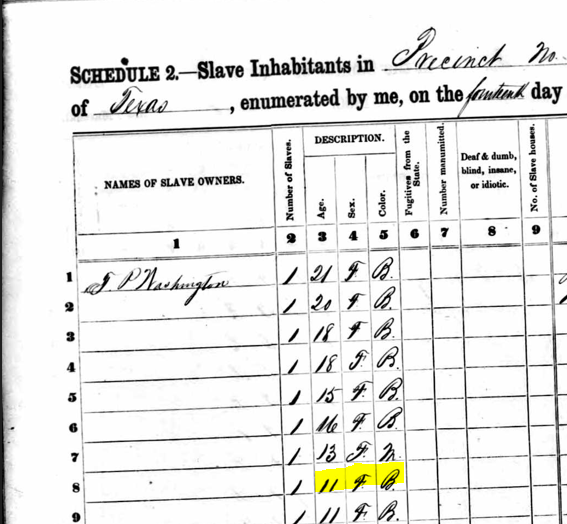

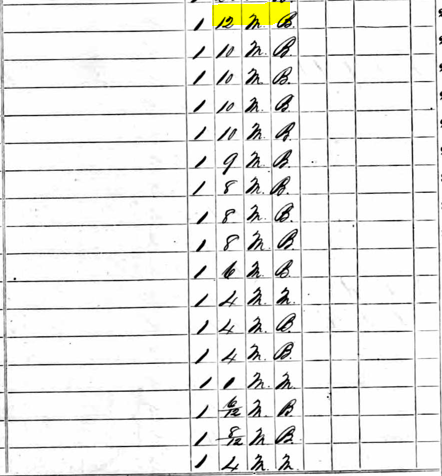

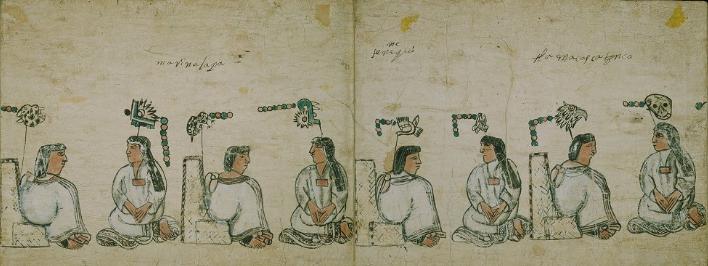

The assumption to see bureaucracies of engineers, architects, bishops, and priests as the product of Bourbon reforms, leads Brockmann to eliminate all bottom-up communication. These bureaucracies communicated constantly with ‘Indians” and Blacks through myriad mechanisms of tribunals and audits. Indigenous communities had their own paperwork bureaucracies. It is therefore strange that Indian and Black voices are almost absent in Brockmann’s study. Either these populations did not get to participate in the new networks of print and sociability (patriotic societies and merchant tribunals) or Brockmann assumes that in the Spanish Empire these populations rarely talked, particularly after the Enlightenment reforms. That their voices dimmed with the Bourbon reforms might well be true, but this is something that requires detailed research rather than vague assumptions.

Brockmann interpretation of Enlightenment is unquestionably important. It shows that something peculiar happened in the Spanish empire as the language of light, patriotism, and utility replaced religious discourses of service among both lay and religious bureaucracies. Utility meant a rejection of abstraction. The Gazeta of Guatemala, the newspaper of the reformers, privileged articles that had demonstrable utility at the very local level, privileging empirical local knowledge over theory. Linnaeus was rejected, indigenous plant taxonomies were embraced.

In this world, the pursuit of utility was a language of commitment for both empire and local community. Brockmann avoids any discussion of “creole” identities leading to friction with peninsular outsiders, the alleged culture of resentment that prefigures the conflict of the wars of independence. The Science of Useful Nature in Central America takes issue with my own work on “science” and creole patriotism (albeit mine is rather on patriotic epistemologies, not science) because the members of these patriotic networks saw themselves as neither ‘Spaniards” nor ‘Creoles’. Since the author focuses on networks of local lay and religious bureaucrats one could argue that patriotism was simply a manifestation of love of service to king, empire, and community to be compensated by grace privileges.

Brockmann shows that with Independence, these bureaucracies continued serving a Federal Republic, no longer a global monarchy. Yet their concerns and modus operandi remained the same. These bureaucracies started to develop networks of all kinds with the British empire, political, economic, and particularly scientific. Brockmann demonstrates that many of the new republican bureaucracies began to transfer colonial archives of maps and reports to the British state as they sought to secure loans, support, or simply old-fashion patronage. Enlightenment came to mean plunder.

Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra is the Alice Drysdale Sheffield Professor of History at the University of Texas at Austin.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.