Note: This article was written and published before Hamas’ brutal attack on Israel on October 7, 2023.

“500 tanks!” exclaimed Henry Kissinger. The national security advisor-cum-secretary of state did not want to believe what he was hearing from the Israeli Ambassador Simcha Dinitz as he recounted the losses sustained by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) during a meeting at the White House on October 9, 1973. It had been three days since Egypt and Syria launched a two-headed assault against Israel, and now, it dawned on Kissinger just how serious the latest Middle East crisis had become.

Kissinger and the rest of Richard Nixon’s administration faced a decision with titanic consequences. Should they send a flagging Israel the tanks, jets, and other weapons it needed to win the war? Or let the belligerents duke it out as is? The president and his administration chose the former. For the Israelis, this was a deliverance that could have come from God himself. Simply put, America’s resupply saved Israel.

The whole of the U.S. government was caught unawares by the outbreak of the Yom Kippur War, also termed the October War. As has been the case many times in American history, the intelligence was wrong. “Israelis do not perceive a threat at this time from either Syria or Egypt,” the U.S. embassy in Tel Aviv reported to Washington on October 1. Yet the threat was all too real. The two Arab states, which Israel had trounced six years earlier in the Six-Day War, resolved to smash Israel and recover the territory they had lost: Egypt, the Sinai Peninsula(and Gaza), and Syria, the Golan Heights.

Egypt and Syria attacked at 2:00 p.m. on October 6, which that year fell on Yom Kippur, the holiest day on the Jewish calendar. The IDF scurried to beat back the onslaught. At first, its defenses were to little avail. Arab tanks, infantry, and planes ravaged the Israelis’ lines. They lost men and military assets left, right, and center.

To the northeast, Syria took the southern Golan and threatened to roll on into the Sea of Galilee and the rest of northern Israel. To the southwest, the Egyptians crossed the Suez Canal and penetrated Israeli positions. Things took a grisly turn on October 8. Israeli losses kept on mounting while the country neared its breaking point. Celebrated general and future Prime Minister Ariel Sharon later called it “the black day” of the IDF.[1]

All the while, Washington debated how it should respond. Israeli requests for supplies came in earnest once it became apparent that, unlike in 1967, this would be no easy victory. Washington’s dilemma was not easy. It feared that a resupply would alienate the oil-rich Arab states. Another variable was the Soviet Union’s resupply of Egypt and Syria, both Moscow proxies. Should the United States respond in kind, the two nuclear-armed superpowers might stumble into war themselves. The stakes were immense.

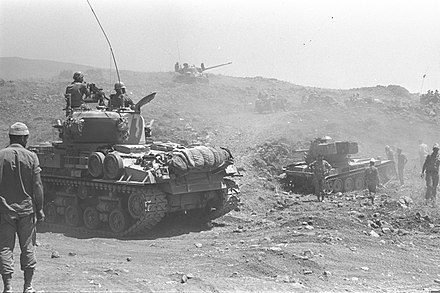

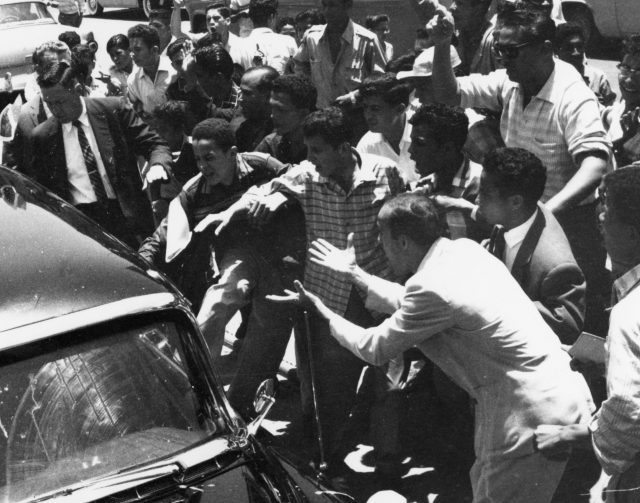

Courtesy of IDF and defense establishment archive, photo no. 8320/298, by Avi Simhoni

Many in the administration favored withholding weapons. This was especially so of Secretary of Defense James R. Schlesinger and the rest of the Pentagon. “Our shipping any stuff into Israel blows any image we may have as an honest broker,” argued Schlesinger.

So began a contentious back and forth between Schlesinger, who feared the consequences of resupply, and Kissinger, who feared the consequences of the reverse. Kissinger was fed up with the Pentagon’s resistance to resupplying the Israelis. “They are anxious to get some equipment which has been approved and which some SOB in [the Department of] Defense held up which I didn’t know about,” he groused to White House Chief of Staff Alexander Haig, also a proponent of a resupply, by phone.[2]

For his part, Nixon authorized providing all the military aid requested by Israel with one caveat. The U.S. government could not be openly complicit in the resupply lest the rest of the world find out. The Israelis would have to collect the weapons themselves from a base in Virginia. “The original order from President Nixon was,” Schlesinger recalled decades later, “‘Give them anything they want as long as they pick them up in El Al [the Israeli flag carrier] aircraft or chartered aircraft.’”

The Department of Defense did not like this one bit. Kissinger later wrote that Pentagon officials were happy “to drag their feet” and stop the Israelis from picking up the arms. “The Pentagon was not cooperative,” remembered Ambassador Dinitz, who said he could not get a meeting with Schlesinger until October 11, five days after the war started.[3] By October 8, the administration realized the existing arrangement was insufficient for the increasingly desperate Israelis. For the IDF to prevail, it needed vast quantities of American weapons. Nixon, who insisted that Israel “not be allowed to lose,” greenlit a major resupply plan on October 9 that he believed would ensure Israel’s survival.

Ambassador Dinitz and the Israelis were grateful. “All your aircraft and tank losses will be replaced,” Kissinger told him as he relayed the president’s decision. “We will get the tanks in even if we have to do it with American planes.” The resupply was on.

With his directive, Nixon came to the Jewish state’s rescue. The decision was not as clear-cut as it may seem in retrospect. He defied recommendations by his Department of Defense and many others in the Federal bureaucracy who were convinced that the resupply was not in America’s economic and political interests. Despite his own anti-Jewish prejudice, Nixon considered Israel a vital pillar of America’s global strategy. He could not forsake it. If Israel were to fall, the Soviets would chalk up another win in the zero-sum game of Cold War geopolitics. “We will not let Israel go down the tube,” Nixon vowed then.

Orchestrating the resupply proved difficult in practice. At first, the administration planned to airlift the materiel via civilian airliners. Yet no private insurers would assume the risk of sending them into a war zone. Richard Perle, then a chief aide to the ardently pro-Israel Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson (D-WA), remembered meeting with a teary-eyed Ambassador Dinitz when he heard by phone that there would be no chartered flights.[4] The resupply was in doubt again.

With civilian planes off the table and all other contingencies exhausted, the administration realized that it had no option but to provide military planes. The president was frustrated by his administration’s failure to get supplies to the Israelis, who were quickly running out of ammunition. “Do it now!” Nixon barked as he ordered the use of military aircraft.[5] In his memoirs, the president recalled urging his administration to “send everything that can fly” to Israel.[6] The airlift, alternatively called Operation Nickel Grass, was underway.

Over the ensuing month, C-5 and C-141 transport jets from the Air Force delivered 22,395 tons of supplies to Israel, stopping to refuel at Lajes Air Base in the Azores on the way. Thanks to indefatigable airmen, the planes would fly more than 500 missions over the course of the airlift. Navy ships and their sailors ferried more supplies by sea. The American resupply matched and surpassed its Soviet counterpart. One of the greatest operations of its kind in history, it was a herculean effort by the U.S. military to provide Israel with the tools to win the war.

The resupply was a godsend for the Israelis. American largesse helped them turn the tide of war, especially in the Sinai. Bolstered by the arms it so desperately required, the IDF repulsed the Egyptian offensive before launching one of its own. Egyptian resistance melted away as the Israelis crossed the Suez Canal and advanced within 99 kilometers of Cairo. On the other front, the Israelis retook the Golan. Israel had won when the war ended on October 25. It did not have to cede any territory to the Arabs. It nonetheless paid a steep price in the form of 2,656 dead and thousands more wounded.

There is little doubt the resupply was essential to the Israeli victory. The IDF was shellshocked and depleted, its supplies dwindling perilously. American arms arrived at just the right time. “Without our airlift, Israel would be dead now,” Kissinger said amid the fighting. Golda Meir, the intrepid Israeli prime minister, wrote in her memoirs that “it undoubtedly served to make our victory possible.”[7]

Had Nixon and his people not come through, there’s no telling what would have happened to the Israelis. They had been staring at their defeat if not destruction. The Arabs were poised to recover the lands they had lost in 1967. Abba Eban, then Israel’s foreign minister, later acknowledged that before the resupply, Israel awaited a cease-fire solidifying the Arabs’ gains. “This would have meant that the Egyptians and Syrians had won the first round of the war,” he wrote.[8] The second round might have been even worse for Israel. A decimated IDF would likely not have been able to defend its territory. Arab leaders, who had a long track record of pledging to “throw the Jews into the sea,” could have had the opportunity to make good on their promise.

It turned out that the Israelis would not be thrown anywhere. They kept control of the Sinai and the Golan. Doing so allowed them to trade the former for peace with Egypt at the end of the decade, based on the land-for-peace formula. That agreement was also a diplomatic triumph for the United States. Once an ally of the Soviet Union, Egypt became a key American partner. Washington’s influence in the Middle East grew as Moscow’s weakened.

To be sure, the United States incurred short-term costs because of the resupply. Most notably, Arab members of OPEC retaliated, embargoing the sale of oil to the United States and other countries backing Israel. They wielded the oil weapon in hopes of forcing Washington to back down. It did not work. Despite facing a quadrupling of the price of a barrel of oil, the Nixon administration and the American people would not be bullied. The resupply continued.

Nixon’s resupply was perhaps the greatest contribution any American president has ever made to Israel. His decision, which scholars and journalists to this day have not fully appreciated, was enormously consequential. To it, Israel likely owes its existence. Consider what has become of the Jewish state in the years since. Israel has come a long, long way since the Yom Kippur War. Today, it is among the wealthiest countries on earth and a global leader in advanced technology. It boasts a formidable conventional military and a nuclear deterrent to boot. It has full relations with six Arab countries, and that list may soon get longer. It is home to vibrant institutions that, whatever their faults, are the most democratic of any in the Middle East. Nixon’s resupply made all that possible.

October 1973 has much to teach us about our current moment. As malignant powers threaten their neighbors worldwide, Washington should follow the Nixon administration’s example. We should not stand by while our foes devour our friends. The resupply is also a reminder of the primacy of national interests. Nixon’s resupply was no act of charity. He may have, in his heart of hearts, wanted to help the Israelis, but he decided with his head. The resupply was what was best for American security and prosperity. Like all other countries, the United States pursued its aims and ambitions, not those of another.

This year, as Israelis commemorate the semicentennial of the Yom Kippur War, they are bound to remember the heroism and sacrifice of those who fought and died for their homeland. And well they should. Israelis are a proud, self-reliant bunch. They do not like counting on others to solve their problems. All the same, they ought to recognize that the United States rescued their country in its hour of greatest peril.

Daniel J. Samet is a Doctoral Candidate at the University of Texas at Austin and an America in the World Pre-Doctoral Fellow at Johns Hopkins SAIS. He is completing his dissertation on U.S.-Israel defense relations. Some of the material in this article has been adapted from Daniel’s upcoming dissertation.

[1]. Ariel Sharon and David Chanoff, Warrior: The Autobiography of Ariel Sharon, 2nd Touchstone ed. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001), 303.

[2]. Transcript of Telephone Conversation, October 7, 1973, 9:35 a.m., Henry A. Kissinger Telephone Conversation Transcripts, Chronological File, Box 22, 7 Oct 1973, 8, Richard Nixon Presidential Library.

[3]. Henry Kissinger, Years of Upheaval (Boston: Little, Brown, 1982), 486.

[4]. Author interview with Richard Perle, May 10, 2023.

[5]. Henry Kissinger, Years of Upheaval (Boston: Little, Brown, 1982), 514.

[6]. Richard M. Nixon, RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon (New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1978), 927.

[7]. Golda Meir, My Life (New York: Putnam, 1975), 431.

[8]. Abba Eban, Personal Witness: Israel through My Eyes (New York: Putnam, 1992), 533.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.