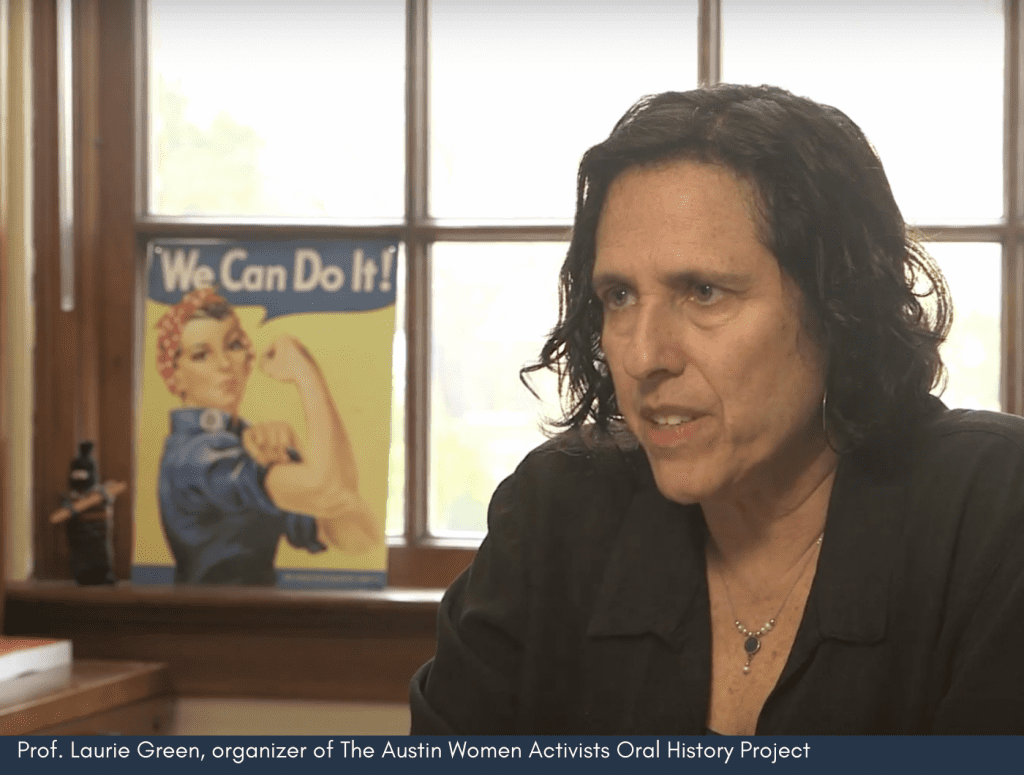

The “Longhorns v. Aggies” Exhibit is currently on display at the H.J. Lutcher Stark Center for Physical Culture and Sports at the University of Texas at Austin

I have lived in Texas my entire life. Because of this, the football game between the University of Texas and Texas A&M University has always played an integral part in the way my family experienced the Thanksgiving holiday. When I was a kid, we often spent the week at my grandparents’ farm in Temple, Texas, where they did not have cable television. So, when the Farmers and Longhorns played, my grandfather would rent a room at a little motel off the interstate highway, and we would all cram in together, sprawled across tiny beds with itchy comforters, and eat bad delivery pizza while watching the big game. My family, however, was all maroon. My grandfather graduated from A&M, my father graduated from A&M, and my younger sister is now a graduate of A&M. I was an anomaly in my family, an artist and writer, and by the time I was a sophomore in high school, I knew College Station wasn’t the place for me. I completed a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in creative writing at Saint Edward’s University, a small, liberal arts school on the hilltop off South Congress Avenue here in beautiful Austin, Texas. And now, I work as the curator at the H.J. Lutcher Stark Center for Physical Culture and Sports, a world-renowned research library with significant gallery space that allows us to host public exhibitions at the University of Texas at Austin. This article is the first in a new series for Not Even Past exploring topics in sports history and the Stark Center archives, with a focus on developing exhibits in public spaces.

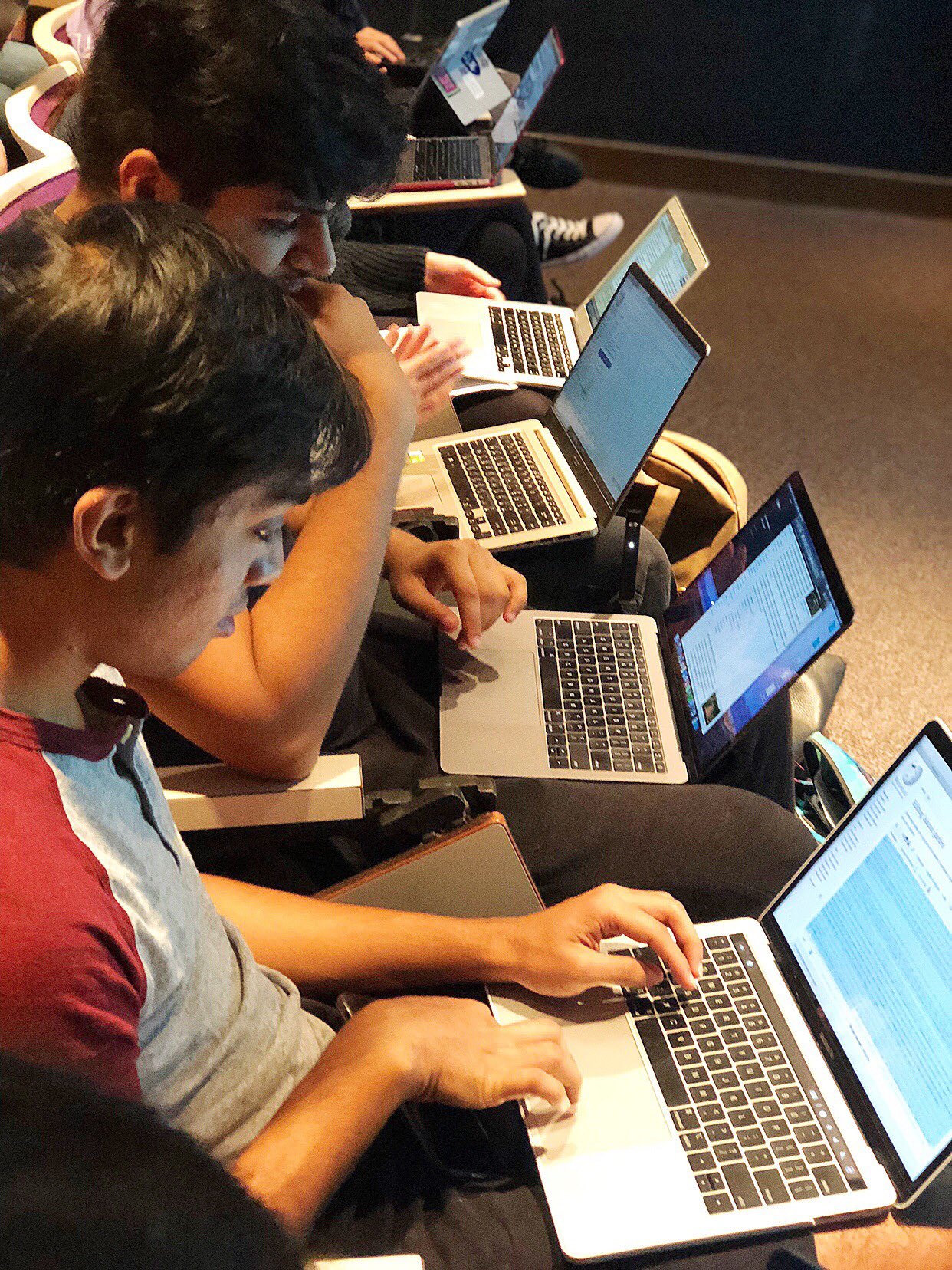

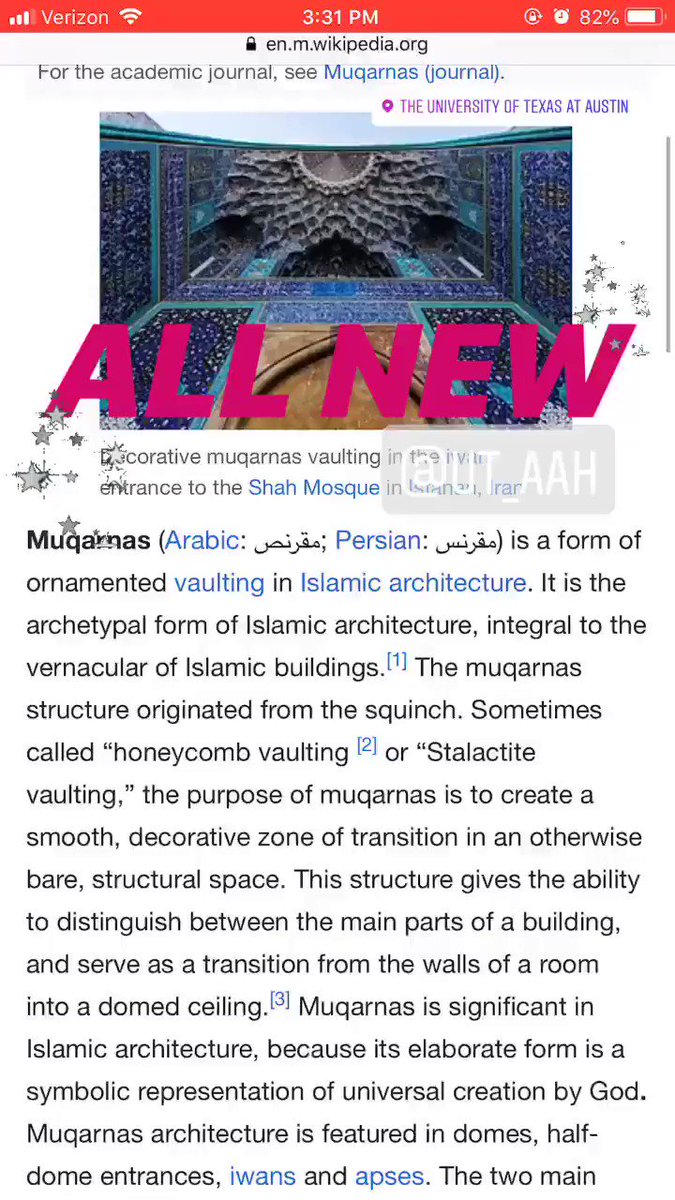

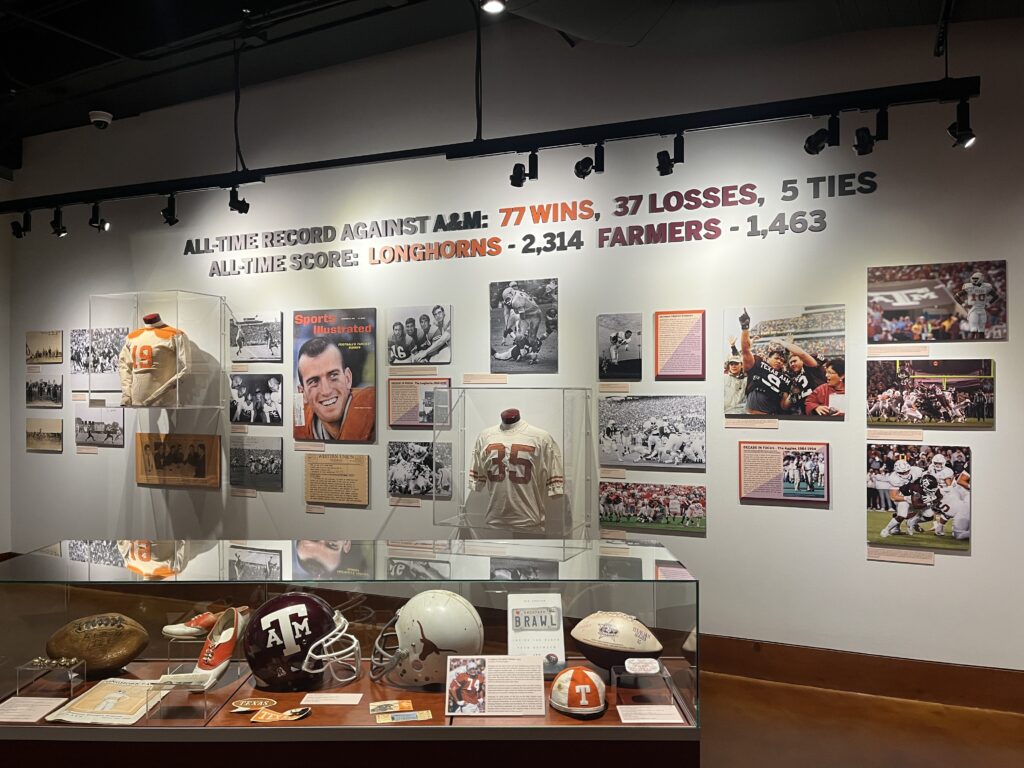

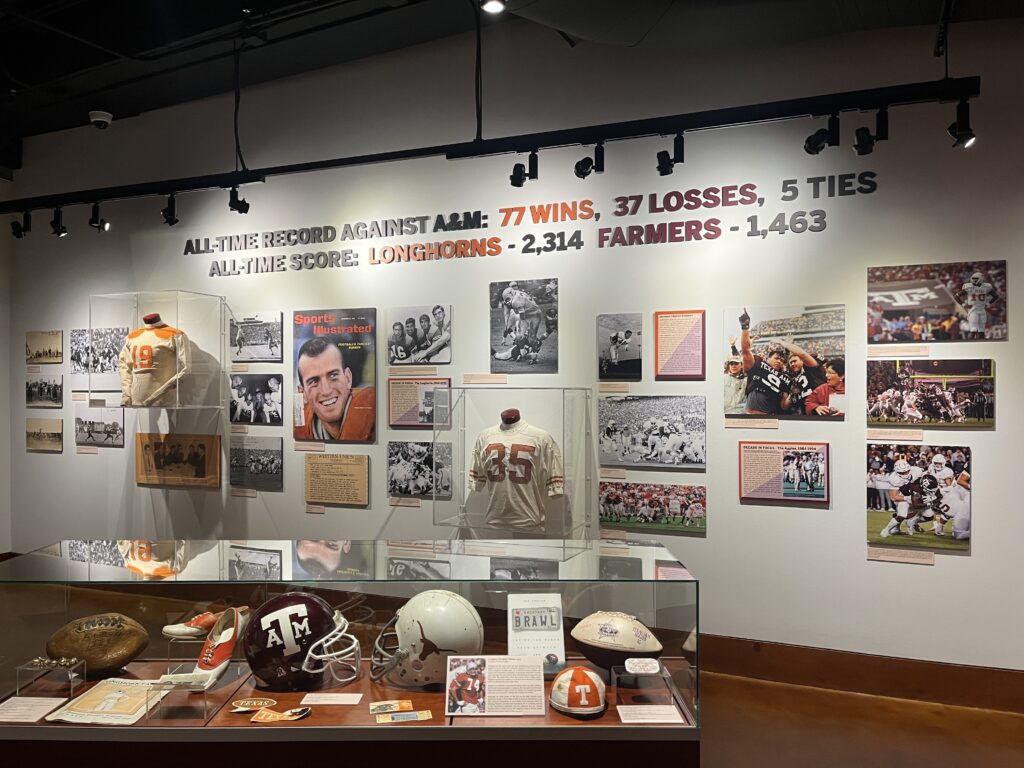

The Stark Center’s latest exhibit, called Longhorns v. Aggies, celebrates the long-running rivalry between the Texas Longhorns and Texas A&M Aggies, specifically the annual Thanksgiving Day football game.[1] The 2025 game was the 120th matchup between the two schools’ football teams. It was the first time in fifteen years that a game between the Longhorns and Aggies was played at DKR-Texas Memorial Football Stadium.[2] Because of that hiatus, most of our current undergraduate students had no personal ties or first-hand connection to this historic game, commonly referred to as The Lone Star Showdown. So, when I sat down with Stark Center Museum Director Jan Todd and we began having conversations about an exhibit covering the long feud between Aggies and Longhorns, we decided that current students deserved to know about the highs and lows of this game’s past, as well as its influence on the cultures, traditions, and identities of each school. The result is an exhibit that attempts to show the complexities of the renewed rivalry.

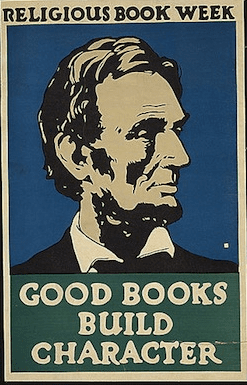

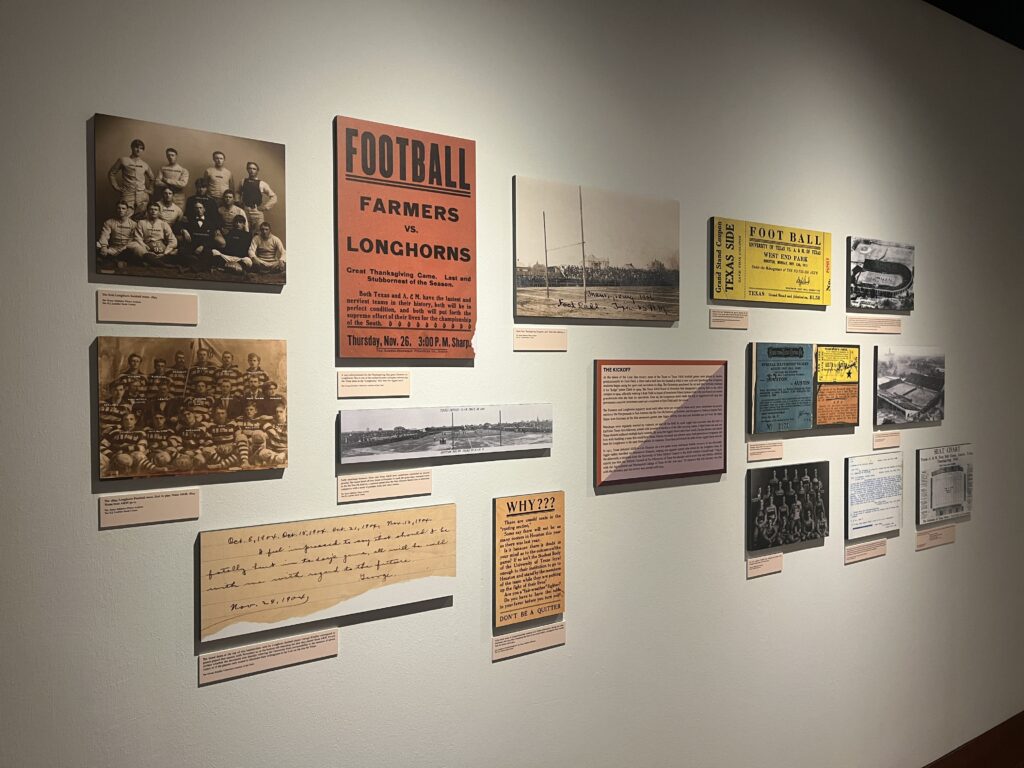

“Longhorns v. Aggies” Exhibit. Courtesy of The H.J. Lutcher Stark Center

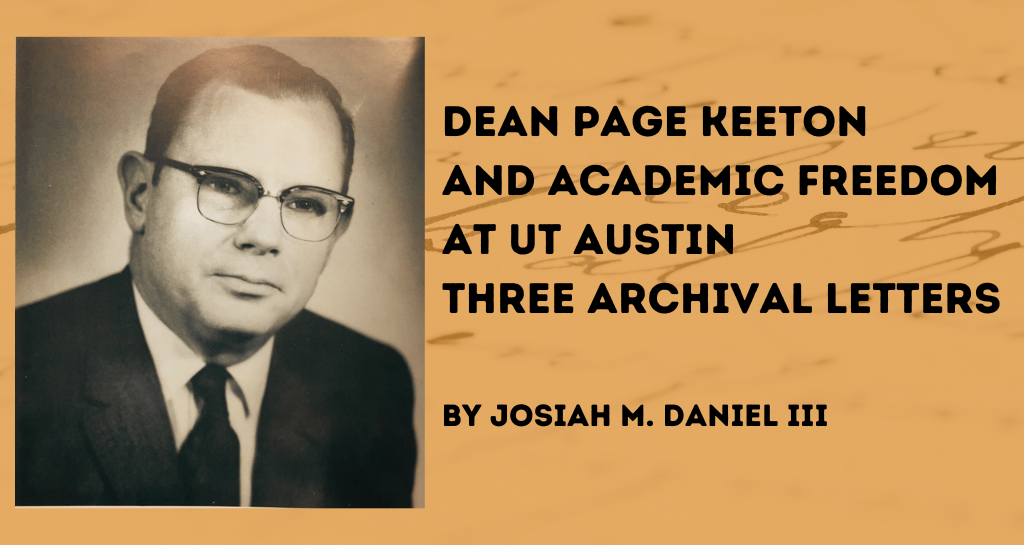

The Origin of Powerhouse Athletics Programs

Although many people assume that The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin) is the oldest state institution of higher learning, Texas Agricultural and Mechanical College (A&M) began educating students in engineering and agricultural science in 1876, seven years before UT Austin opened its doors to students. From those earliest times, however, the two schools regarded each other as rivals. UT Austin offered higher education focused on liberal arts and the humanities. Its campus was located in downtown Austin, the state capitol. The student body was co-ed from its inception. The Aggies, on the other hand, emphasized a curriculum centered on agriculture and engineering. Theirs was a rural campus with an all-male student body required to participate in Corps of Cadets military training. After the two schools began meeting for an annual football game in 1894, the frictions between the rural “Farmers” of A&M and the big-city “Steers” of Texas only grew. We tell “Aggie jokes.”[3] They call us “t-sips.”[4] The lyrics in each school’s fight song bids the other farewell. The rivalry deepened as UT Austin won fourteen of the first seventeen games.[5] Folks in College Station were frustrated.

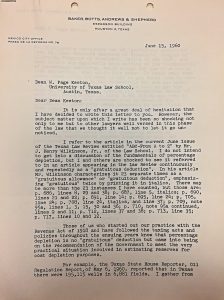

In 1909, the Aggies hired Charley Moran as their new head football coach and assigned him one task: build a team that could beat Texas. After recruiting players from other successful collegiate programs in the American South, the A&M football team did just that, winning back-to-back games in the 1909 season and the lone game against Texas in the 1910 season. Tensions ran especially hot during this period. On-field play was remarkably violent with players from both teams regularly suffering major injuries. Off the field, supporters clashed, taunting and fighting each other—Longhorn fans once carried broomsticks and marched in a mockery of A&M’s Corps of Cadets, which led to a massive brawl. A University of Texas student suffered knife wounds in a rumble after the 1908 game–the wounds were non-fatal and A&M officials issued a sincere public apology. In 1911, the game was played on neutral territory in Houston, as the headline event of the city’s No-Tsu-Oh Festival. Texas defeated A&M 6-0 on a late game scoop-and-score fumble recovery. After the game, A&M’s Corps of Cadets marched on downtown Houston, taking over city blocks and instigating physical altercations with anyone perceived to be affiliated with the University of Texas. Swarms of police were required to restore the peace. In the aftermath, the Athletics Council at UT sent a telegram to the Athletics Council at A&M:

Dear Sir:

Referring to my telegram of November 8 and letter of November 9, I beg to inform you that the Athletic Council of The University of Texas has decided not to enter into any athletic relations with the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas for the year 1912.

Very respectfully,

W. T. Mather Chairman of the Athletic Council The University of Texas

“Longhorns v. Aggies” Exhibit. Courtesy of The H.J. Lutcher Stark Center

The Farmers’ Athletic Council was, apparently, fine with the idea and the schools did not face each other again until 1915.[6]

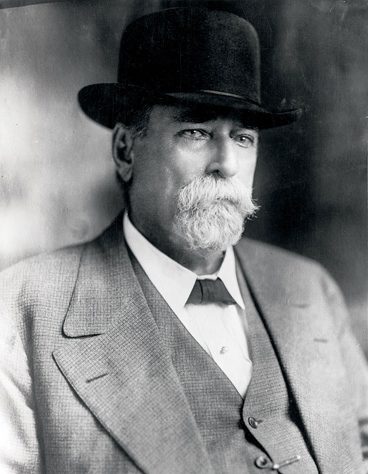

This is significant because the loss in revenue from the already ubiquitous rivalry, deemed the “richest attraction in the Southwest,” left both schools’ athletics programs teetering on the brink of bankruptcy.[7] Enter L. Theo Bellmont. In 1913, Bellmont was hired as the University’s first director of athletics. Bellmont’s hiring was promoted by Lutcher Stark, a great benefactor of Texas Athletics, who would later become the youngest man ever appointed to The Board of Regents.[8]

It was Bellmont’s job to organize physical education classes for men and to run the sports programs. One of his first acts was to establish an advisory board for Athletics and then to petition for his new Athletic Council to have financial oversight for running the games and raising funds. First, he appealed to President S. E. Mezes to grant him and the Athletic Council complete management of all athletic events. His wish was partially granted in 1913 and then fully in 1914. Second, he began the formation of a new athletic conference, the Southwest Athletic Conference. The Southwest Athletic Conference came to be known, more famously, as the Southwest Conference, which existed from 1915 until 1996 when Texas, Texas A&M, Texas Tech, and Baylor moved to the Big XII Conference in search of television revenue from football and basketball games.

“Longhorns v. Aggies” Exhibit. Courtesy of The H.J. Lutcher Stark Center

Meeting with A&M officials in “behind-closed-door sessions” in 1914, Bellmont was able to navigate a renewal of the rivalry between Aggies and Longhorns through the establishment of the Southwest Conference and a still unconfirmed agreement by the Aggies to fire Coach Charley Moran.[9] Essentially, the first pause in the Lone Star Showdown led both athletic departments to face their greatest crisis to date, very nearly bankrupting and ending them entirely. And the renewal of the rivalry, through the actions of Theo Bellmont, gave birth to the modern intercollegiate athletics program at the University of Texas.

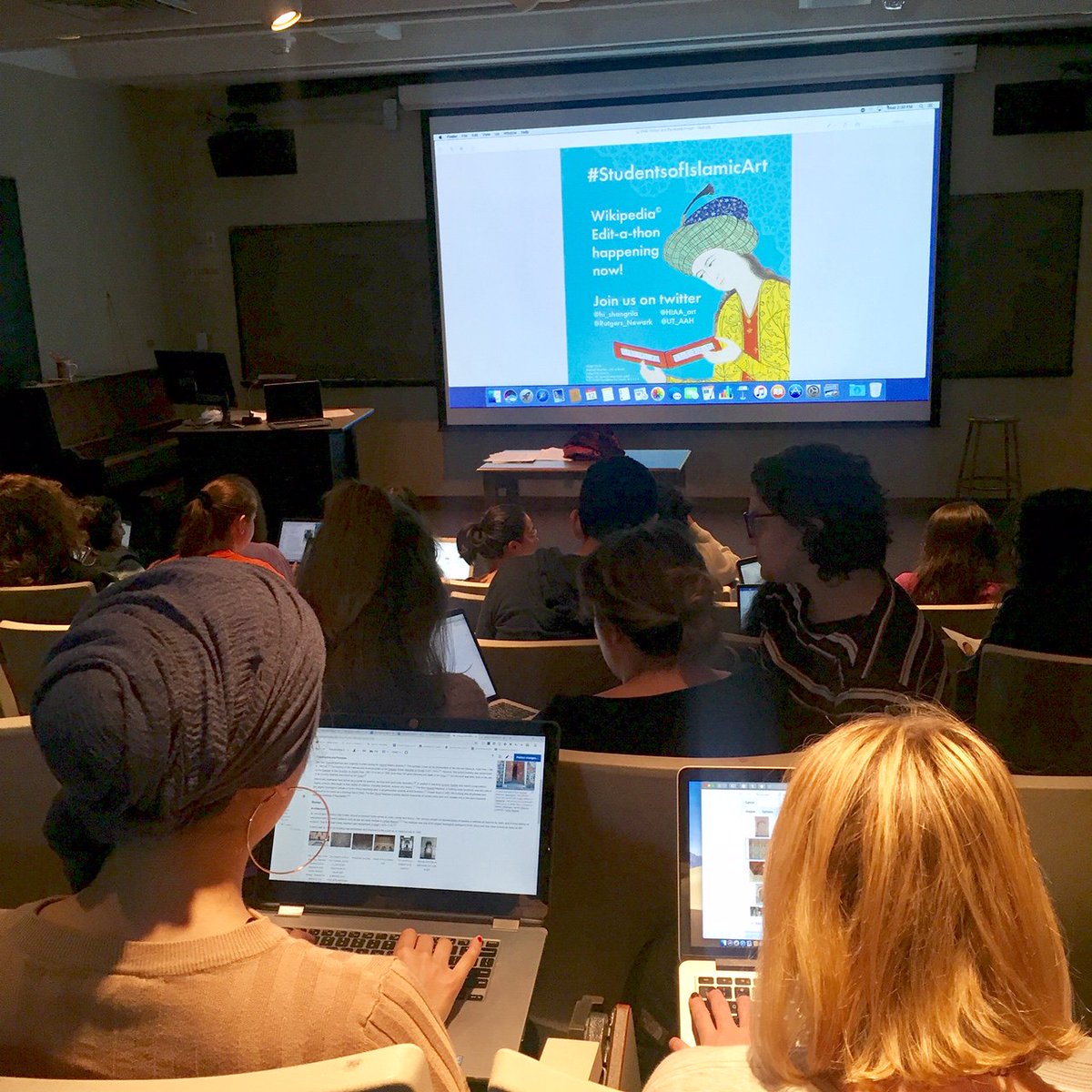

Shaping the Exhibit

This past summer I was blessed with research help from Valeria Misakova, an undergraduate Stark Center intern, who normally attends Notre Dame University. Valeria spent dozens of hours scanning The Daily Texan and The Cactus yearbooks for information on these historically significant games and teams. Stark Center Archivist Caroline De La Cerda was a tremendous resource on this project, including connecting me with archivists at Texas A&M’s Cushing Library who helped accumulate assets related to Aggie history and culture that can’t be found in our own archive. Sports archivist Patty McCain and Stark Center Associate Director Kim Beckwith also contributed to helping us find artifacts to display and getting the history “right.”

“Longhorns v. Aggies” Exhibit. Courtesy of The H.J. Lutcher Stark Center

This exhibit, with its rich history, is shaped by chapters or subsections, rather than a rigid chronological organization.

1. “The Kickoff” presents the origins of football at each school and the early matchups.

2. “Raising Cain” documents the colorful history of off-field hijinks.

3. “Siblings First, Rivals Second” memorializes the 1999 Bonfire Tragedy and the Unity response.

4. Untitled, the longest wall in the gallery and primary backdrop of the exhibit, features photographs and artifacts that showcase the history of the games played on the field, from 1915 all the way up to the game in 2024, highlighting specific decades for each team as well as recognizing the three Heisman Trophy winners that played in the Lone Star Showdown.

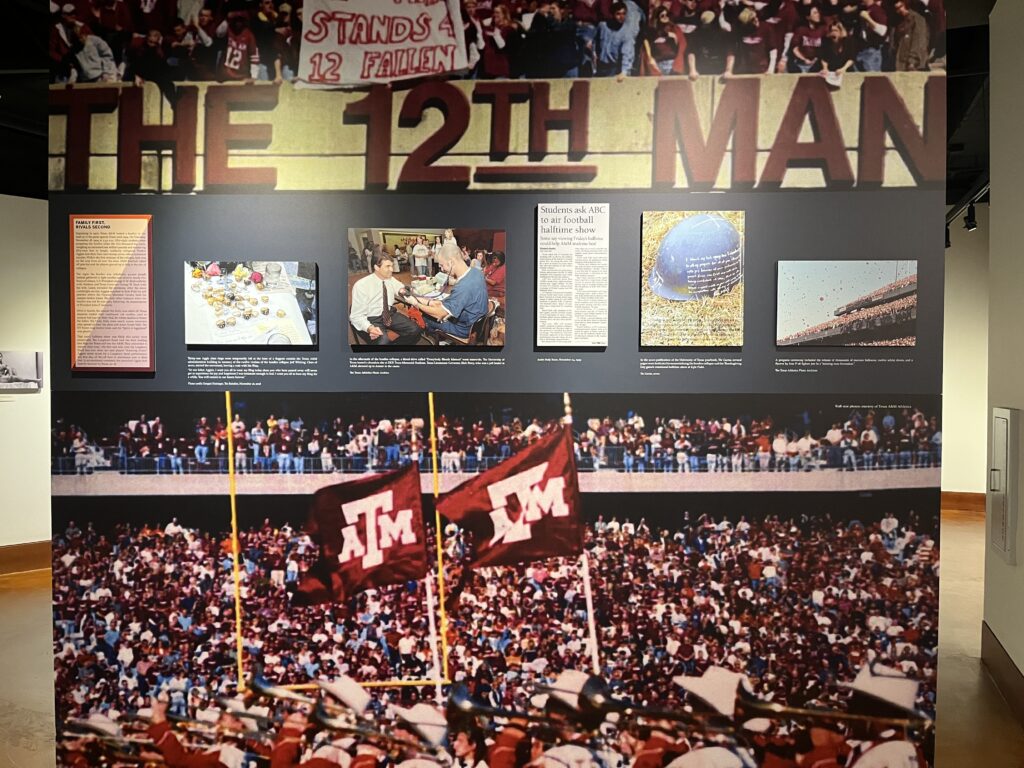

5. Two walls, presented side-by-side in burnt orange and maroon, respectively, showcase the various cultures and traditions at each school, particularly those that were formed out of this rivalry.

6. “Cover Art” features a colorful collage of gameday programs spanning the past 100 years of games played between Texas and Texas A&M.[10]

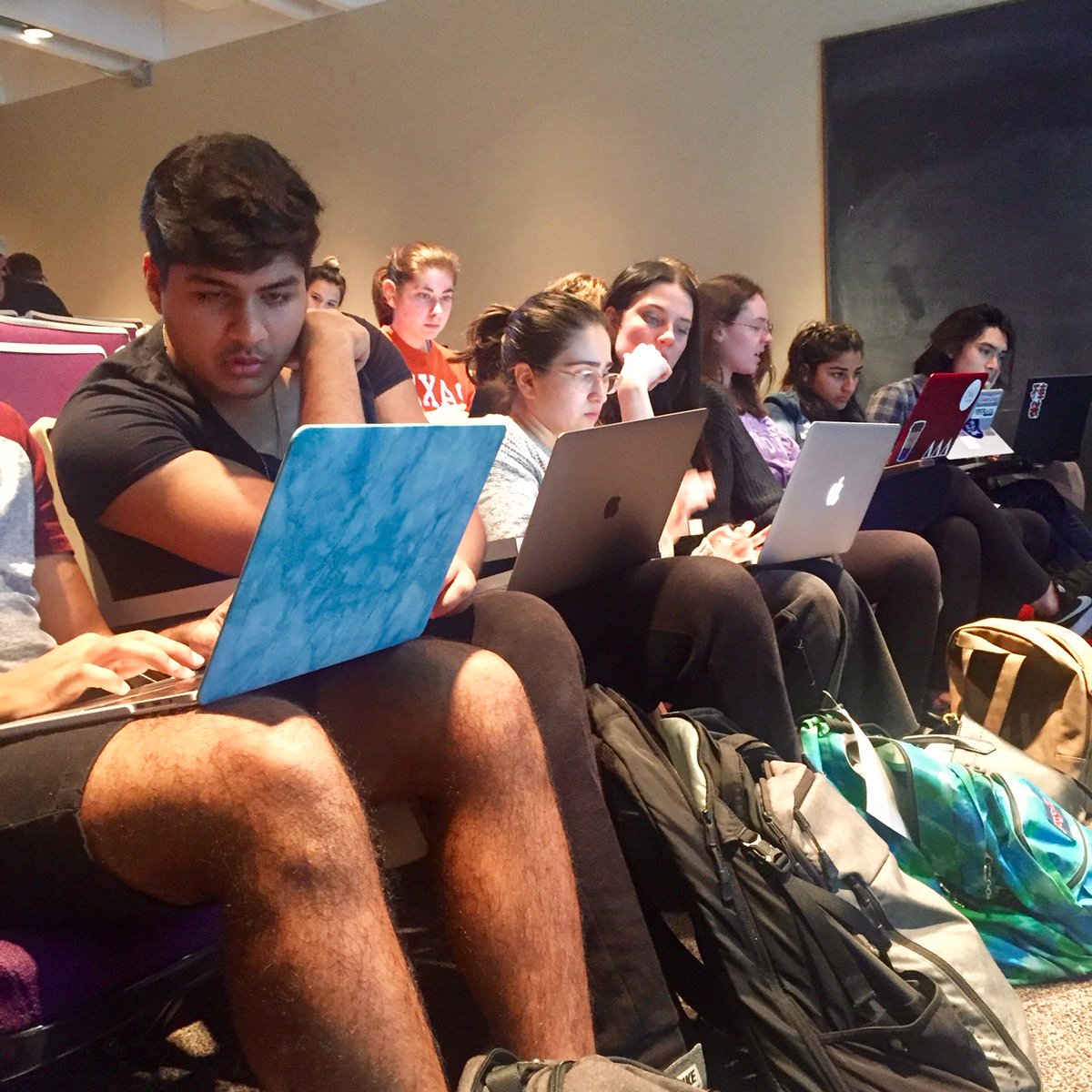

“Longhorns v. Aggies” Exhibit. Courtesy of The H.J. Lutcher Stark Center

If you have not been to the Stark Center, or you have not visited since we opened Longhorns v. Aggies, please drop by and explore our space and learn more about the history of this Texas-sized rivalry. The Stark Center is located on the 5th Floor of the North End Zone at DKR-Texas Memorial Football Stadium, open Monday-Friday, 9am until 5pm. There is no charge for admission, and all fans are always welcome in our space.

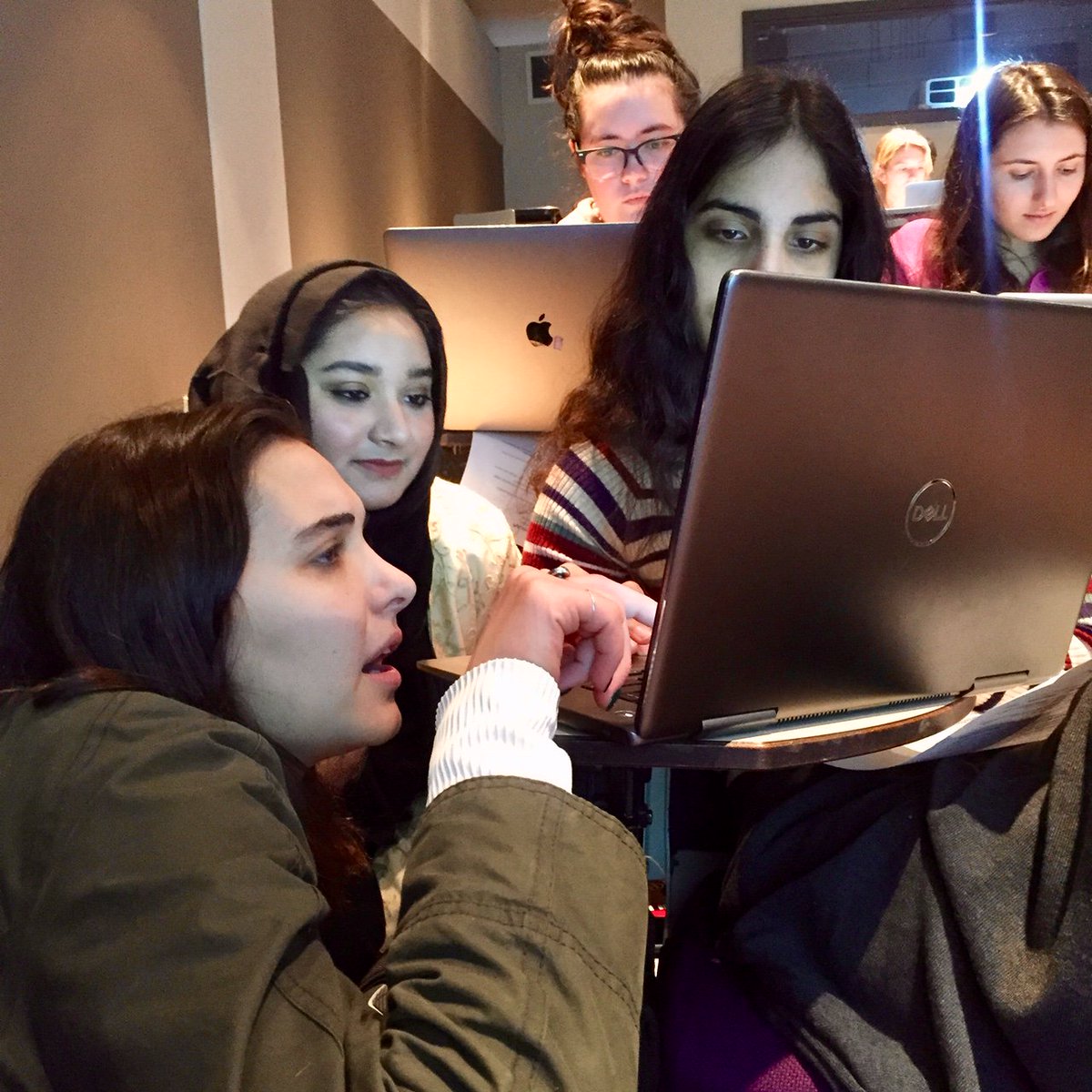

“Longhorns v. Aggies” Exhibit. Courtesy of The H.J. Lutcher Stark Center

“Longhorns v. Aggies” Exhibit. Courtesy of The H.J. Lutcher Stark Center

Kyle Martin has worked as the Curator of the Stark Center since September 2024. His primary fields of work are writing, designing, and curating new exhibits and other creative projects related to the promotion, marketing, and enhancement of the Stark Center and its missions. He also serves as the technical editor of Iron Game History.

[1] Or Thanksgiving-adjacent; Longhorn/Aggie football games have also regularly been played the day after Thanksgiving, as this year’s game was. The first time Aggies and Longhorns played football against each other on Thanksgiving Day was 1900. Since then, the game has, typically, been scheduled on or near the holiday.

[2] In 2011, Texas played Texas A&M at Kyle Field in College Station. The Longhorns won 27 – 25. At the conclusion of the 2011-2012 academic year, Texas A&M Athletics left the Big XII Conference to join the Southeast Conference, a move that shocked both fan bases and led to the Longhorns and Aggies no longer facing each other on a regular season schedule. The teams did not play again until 2024, at Kyle Field in College Station, when the Texas Longhorns played their inaugural season in the Southeast Conference, following their own departure from the Big XII. The pause in play was so monumental that state legislators attempted to pass bills forcing the restoration of the rivalry. They were unsuccessful in doing so. As a result, the 2025 match up was the first played in Austin—at DKR-Texas Memorial Football Stadium—in fifteen years.

[3] Here’s an example of an Aggie joke that scores points against A&M and the Longhorns’ other rival, OU:

Did you hear about the Aggie who moved to Oklahoma? The move raised the average IQ in both states.

[4] Or “Tea-sip” is a label that Aggie students gave to Longhorn students to mock their perceived “snootiness” or elitism, one who hoists a pinky up and sips at their tea.

[5] Played in the span of 14 years; the schools often played twice per season at this time. There were two games that ended in a tie (1902 and 1907). Also worth noting, the Aggies did not score a single point in their first 8 matchups against Texas.

[6] From a class paper by Bill Gunn and Jimmy Viramontes, “An Early Athletic Administration Problem at The University of Texas, A Problem Presentation” for ED. AD. 392. Dr. Kenneth E Mcintyre-Professor, by. Found in the Texas Athletics Media Archives, The H.J. Lutcher Stark Center for Physical Culture and Sports.

[7] Ibid

[8] Here, at the research center which bears his name, we credit H.J. Lutcher Stark as the “father of the Longhorn logo,” when he purchased blankets for the 1914 Texas football team that featured the image of a longhorn on them. This was the first time a longhorn logo—a full head and neck with details like eyes, fur, and spots—was used on official gear at the University of Texas, cementing the mascot/brand.

[9] Gunn and Viramontes, “An Early Athletic Administration Problem.” Also note, Moran was beloved by the Farmers and colloquially referred to as “Uncle Charley” but hated by Longhorns who believed he coached his teams to seek out plays that would injure opposing players. In 1910, Longhorn fans developed a new cheer for football games against A&M: “To hell, to hell with Charley Moran, / and all of his dirty crew / If you don’t like the words of this song, / to hell, to hell with you.”

[10] What can football programs tell us about the past? As it turns out, plenty. The many Texas v. A&M football programs featured in this collage have helped to create the public images of both the Longhorns and Aggies as they evolved over time. Cover art has been used to foster traditions and emotions that surround the game experience, but also to mark changes in technology and historic events, giving us a glimpse into the mindset of Texas and A&M students through the years.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.