By David Crew

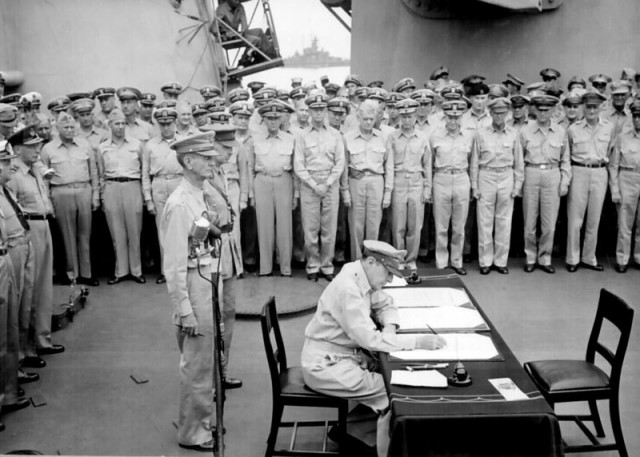

Ralf Breker wearing the VR headset in front of his VR view of Auschwitz (via BBC News).

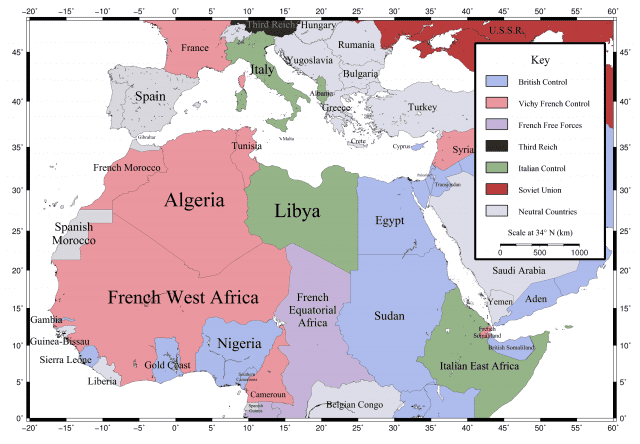

The Bavarian State criminal office (LKA) in Munich, Germany has developed a 3D virtual reality model of the infamous Auschwitz concentration and extermination camp to be used in trials of Nazi era war criminals who still remain alive. Drawing upon original blue prints, laser scans of remaining buildings and contemporary photographs, this VR model allows prosecutors, judges and lawyers to view Auschwitz from almost any angle. The digital imaging expert, Ralf Breker, who developed this technology says that it can be used, for example, to determine whether someone who was a guard in Auschwitz in a specific watchtower could or could not see crimes committed in another part of the camp. Breker thinks the technology he developed will soon be used in other types of criminal proceedings because it allows investigators to re-create crime scenes that no longer exist as they were when the crime was committed. He hopes, however, that when the German legal system no longer needs his 3D model of Auschwitz, it will be given to a museum so that it does not fall into the hands of anyone wanting to turn it into a computer game.

For further details and an interview with Ralf Breker, see

Marc Cieslak, “Virtual reality to aid Auschwitz war trials of concentration camp guards”

![]()

Also by David Crew on Not Even Past:

The Normandy Scholar Program on World War II.

The Years of Extermination: Nazi Germany and the Jews, 1939-1945 by Saul Friedländer (2007).

Normal Pictures in Abnormal Times.

![]()