Straight from the headlines: ISIS destroys the temple of Bal at Palmyra. Looters steal friezes from Greco-Roman sites in Ukraine under the cover of conflict. A highway is built through an ancient Mayan city in the Guatemalan highlands, the legacy of decades of near-genocidal internal conflict. Why is the loss of human patrimony important, especially in the context of the loss of lives? How can we begin to explain why both are worthy of our consideration? And what can high school or college educators and their students do about it? Our first roundtable features three experts from the University of Texas who’ve taken the destruction of sites where they’ve worked and lived seriously, and are working to raise awareness of the importance of antiquities in danger around the world, and share simple steps to raise awareness about the problem and how to get involved.

Episode 71: The Rise and Fall of the Latvian National Communists

For a period in the 1950s known as the Khruschev Thaw, the Soviet Republics enjoyed a brief moment of relative autonomy from the heavy handed leadership of Moscow. Latvia, a small republic on the Baltic Sea, took prime advantage of this period of liberalization under the leadership of a group called the Latvian National Communists. They saw a way forward that diverged considerably from Moscow, and took concrete steps to resist Russification of Latvia’s politics and culture. The Thaw was short lived, however, and the Latvian National Communists were eventually thwarted and the republic brought back into the Soviet fold. Guest Mike Loader gives an enthusiastic look at this high drama at the peak of the cold war, which gives us a glimpse into the inner workings of the Soviet Union from a different perspective.

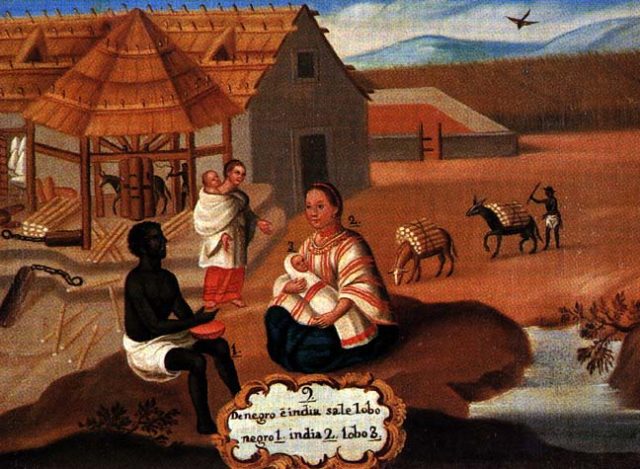

Race and Status in Colonial Latin America

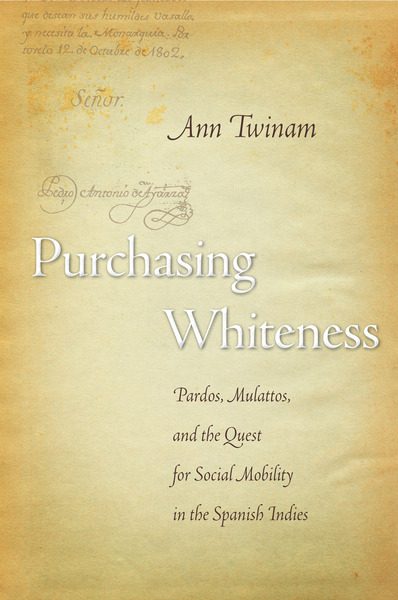

Classic and New Reading on Race and Status in Colonial Latin America

by Ann Twinam

Magnus Mörner, Race Mixture in the History of Latin America. Boston: Little, Brown, 1967.

While Morner proposed a more static view of the construction of racial categories in colonial Spanish America, his work is fundamental to understanding where we started.

Douglas Cope, The Limits of Racial Domination. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1994.

Cope’s work complicates Mörner’s by emphasizing the fluidity of socioracial categories in Spanish America. He suggested that ““a person’s race might be described as a shorthand summation of his social network.”

Matthew Restall, The Black Middle: Africans, Mayas, and Spaniards in Colonial Yucatan. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2009.

Matthew Restall’s many publications highlight the repercussions of Native and African interactions, a theme less researched until recently.

Joanne Rappaport, The Disappearing Mestizo: Configuring Difference in the Colonial New Kingdom of Granada. Durham: Duke University Press, 2014.

Joanne Rappaport provides nuanced understandings of the complexities of racial construction, exploring how Spanish Americans created their own socio-racial identities. (Reviewed in depth on NEP by Adrian Masters.)

Purchasing Whiteness: Race and Status in Colonial Latin America

By Ann Twinam

Let’s start with a question and a comparison.

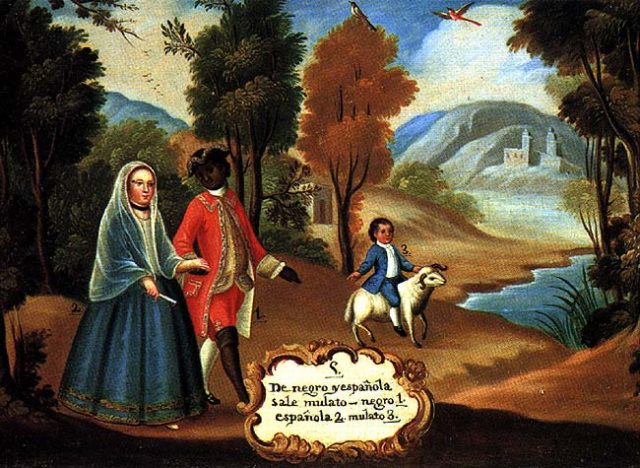

What do you think would have happened if a free mulatto — someone of mixed white and African heritage — living in New York or Virginia, had sent a letter to either of the Georges, either King George III (1760-1820) or President George Washington (1789-1797) asking if he might purchase whiteness? Do you think he would have even received a reply, much less transformation to the status of white? The very idea that mulattos could pay to become “whites” or that an English king or a U.S. president might grant such a change seems unbelievable — because it was.

Yet, during the same period in the Spanish empire, such alterations for mulattos –also known as pardos or castas — became possible. This was so, even though the Spanish state had also institutionalized severe discriminations against those of mixed African descent, just as in the British Empire and in the American republic. Laws forbade their practice of numerous occupations including physician, notary, lawyer, priest, the holding of public offices, service in the regular military, entrance to universities, and marriages with whites. Still, it was also possible for Cuban Manuel Baez to receive a royal decree in 1760 that erased “the defect that you suffer from birth and leave you able and capable as if you did not have it, repealing this time in your favor whatever laws, ordinances or constitutions speak otherwise.”

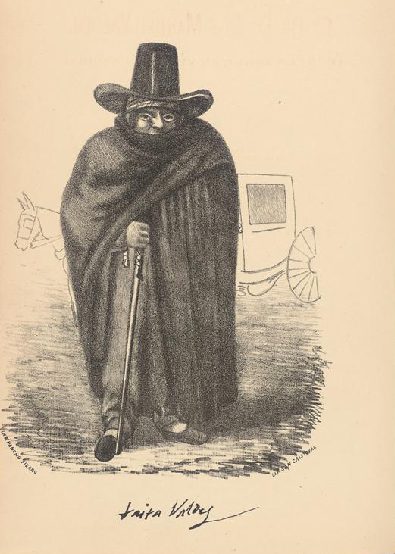

By 1795, the Spanish crown had institutionalized the purchase of whiteness through a process called the gracias al sacar. An elite cohort of pardos and mulattos could apply and pay for a decree that converted them to whites. In 1796, merchant Julian Valenzuela bought a decree from the king and Council of the Indies that “dispensed” his status as a “pardo.”

At the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth centuries in Spanish America,there was vigorous and serious debate concerning the civil rights of those of mixed descent. It not only led the Council of the Indies to endorse the continued whitening of deserving pardos and mulattos, but also to consider eliminating some of the discriminations against all the castas. It meant that by 1812, the Cortes of Cádiz, tasked with writing a constitution for the Spanish empire, would continue to widen opportunities for pardos and mulattos by ordering the desegregation of universities throughout the Indies. Such actions would occur 150 years before the U.S. government in the 1960s would demand similar measures for colleges and universities.

Such contrasts between Spanish and Anglo America lead to other questions. What made it possible for pardos and mulattos in the Spanish empire in the mid eighteenth century to apply for whiteness? Why would the crown take them seriously? What does this reveal about the different histories and the different ways that the Anglo and the Iberian worlds have constructed and treated issues of race?

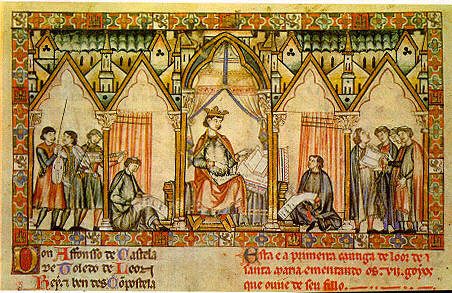

Some deep-rooted Spanish practices facilitated the progression from slavery to freedom to vassalage that enabled mutable racial status. Even as both sides of the Spanish Atlantic acknowledged hierarchies of exclusion that privileged whiteness and rank, some possibilities for inclusion remained open. The medieval law code of the Siete Partidas (1252-1284), for example, acknowledged that slaves would naturally seek freedom, establishing the potential for purchase or grant of liberty with the acquiescence of the state.

Spanish traditions also uniquely combined with the American environment to open interstices for newly arrived Africans to negotiate pathways. The legal recognition that free women always gave birth to free babies had an incalculable impact in the Americas, given the potential motherhood of millions of indigenous women. It provided male slaves with the option of automatically freeing sons and daughters borne by Native and later by free casta partners. Slaves, free blacks, pardos, and mulattos could access the system, seeking legal remedies for mistreatment. Laws proved color blind, permitting acquisition of possessions, as well as secure passage of property to succeeding generations.

The passage of time also mattered. The first waves of Africans disembarked centuries earlier in the Indies than in Anglo America. The royal insistence that slaves become Catholics also had a profound influence, even though African beliefs persisted and blended. As the centuries passed, a shared religion united the inhabitants of the Indies forging them into a Spanish Catholic “us.” Because they were coreligionists and neighbors whose families had lived for generations in the Americas, blacks, pardos, and mulattos in the 1620s and 1630s received permission to organize militia units and take up arms with whites to defend their mutual homeland against foreign enemies.

Such evidence of royal service moved participating castas from the category of “inconveniences,” to the status of vassals enjoying the traditional benefits of reciprocity. Those who performed services had the right to request favors; the duty of the monarch was to reward them. For that reason, the Council of the Indies would seriously consider the casta petitions that arrived in the mid eighteenth century requesting the purchase of whiteness. The history of the whitening gracias al sacar thus becomes inextricably linked to centuries of struggles by Africans and their mixed-blood descendants to move from slavery to freedom, to status as vassals, and finally, after independence, to citizenship.

The gracias al sacar emerges as but one variant — an official one — of widespread and unofficial practices that had facilitated pardo and mulatto mobility for centuries. The ability to purchase whiteness proved critical, but not because of the few who applied for it or the even fewer who received it. Rather, its history coincides with this larger and mostly untold story of casta mobility in Spanish America. The extent to which such struggles failed and succeeded provides striking insight into those processes of exclusion and inclusion that shaped the texture of discrimination within the Spanish empire. Understanding those differences highlights the divergent historical paths followed in Anglo and Latin America, the consequences of which reverberate even today.

Purchasing Whiteness: Pardos, Mulattos and the Quest for Social Mobility in the Spanish Indies by Ann Twinam

To read more about interpretations of race and status in colonial Latin America, click here.

Articles on Not Even Past about race and slavery in Latin American can be found here.

Episode 70: Slavery and Abolition in Iran

The untimely death of a black man causes a stir in the press, causing intellectuals and activists to point to a long history of slavery and institutionalized racism in America. This isn’t a headline from 2015 (although it could be); it’s a description of how the Iranian press treated the assassination of Malcolm X. Iran, like many countries in North Africa and West Asia, has its own history of slavery, one that has been slowly forgotten in the century since its abolition; a history that is finally coming to light with a new generation of Iranian and Iranian-American historians. Beeta Baghoolizadeh, a UT alumna who is now a doctoral candidate in History at the University of Pennsylvania, shares both the history of abolition in Iran and some personal observations on the difficulties of researching a topic long considered taboo in Persian society.

Presidents Past

Thinking about the future POTUS, with the first debate of the 2016 campaign on TV tonight?

Read up on Presidents of the past in articles we have posted here on Not Even Past.

Let’s begin with Jack Loveridge’s review of Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72: “Thompson, author of Hell’s Angels and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas has the right kind of eyes to see the corruption, the lunacy, and the sheer depravity of choosing a chief executive in modern America.”

You might not be surprised to learn that we have more articles on LBJ than another other President. Among them, Mark Lawrence wrote about LBJ and Vietnam: A Conversation and The Prisoner of Events in Vietnam.

In Liz Carpenter, Texan and Lady Bird Johnson in Her Own Words by Michael Gillette we see LBJ through the eyes of two remarkable women. In A Rare Phone Call from One President to Another, Jonathan Brown recounts the first crisis of the Johnson presidency and the phone call he made to Roberto F. Chiari, President of Panama, to try to resolve it.

We have posted a number of reviews of books about Ronald Reagan. Simon Miles reviewed Reagan on War: A Reappraisal of the Weinberger Doctrine, 1980-1984, by Gail E. S. Yoshitani (2012). Joseph Parrott reviewed The Rebellion of Ronald Reagan: A History of the End of the Cold War, by James Mann (2010). The Age of Reagan: A History (2008) by Sean Wilentz was reviewed for us by Dolph Briscoe IV. And Jonathan Hunt wrote about the summit meeting between Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in Reykjavik, Iceland in 1986, to discuss the future of nuclear weapons: The Strangest Dream–Reykjavik, 1986.

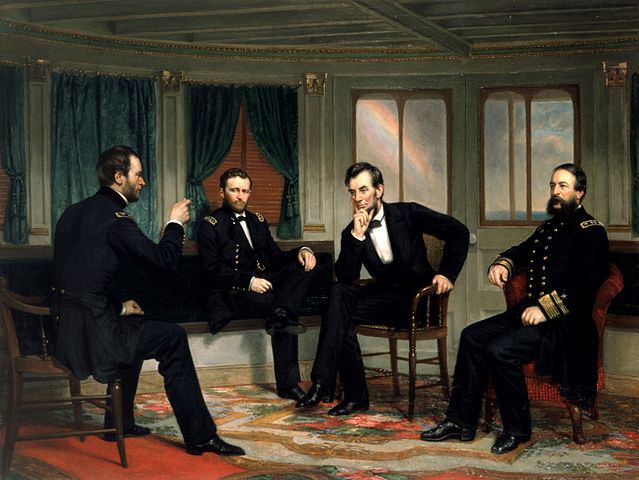

Abraham Lincoln is treated in a variety of contexts. Charley Binkow tells us about a project to digitalize everything in Lincoln’s archive in Honest Abe’s Archive. Remember Spielberg’s film, Lincoln, about the difficult passage of the Emancipation Proclamation? You can re-read Nicholas Roland’s discussion of the treatment of history in the film in A Historian Views Spielberg’s Lincoln. And Henry Wiencek reviewed Eric Foner’s best-selling book about the history of the Abraham Lincoln’s views on American slavery, southern secession and the convergence of events that produced the Emancipation Proclamation, The Fiery Trial. Hannah Ballard shifts our attention away from the Lincoln of the Civil War, slavery and Emancipation to the Lincoln who presided over Native American massacre in her review of 38 Nooses: Lincoln, Little Crow, and the Beginning of the Frontier’s End by Scott W. Berg (2012)

Ulysses S. Grant attracted the attention of H.W. Brands who wrote a biography of one of our most maligned Presidents and Mark Battjes reviewed Grant’s extraordinary Personal Memoirs.

Aragorn Storm Miller reviewed a book about foreign-policy advisors to George W. Bush: Rise of the Vulcans: The History of Bush’s War Cabinet by James Mann (2004)

Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America by Rick Perlstein (2008) was also reviewed by Dolph Briscoe IV.

Lior Sternfeld reviewed a book about Woodrow Wilson and national self-determination after WWI in The Wilsonian Moment by Erez Manela (2007)

Let’s finish up with a failed Presidential campaign: Michelle Reeves reviewed Henry Wallace’s 1948 Presidential Campaign and the Future of Postwar Liberalism by Thomas W. Devine (2013).

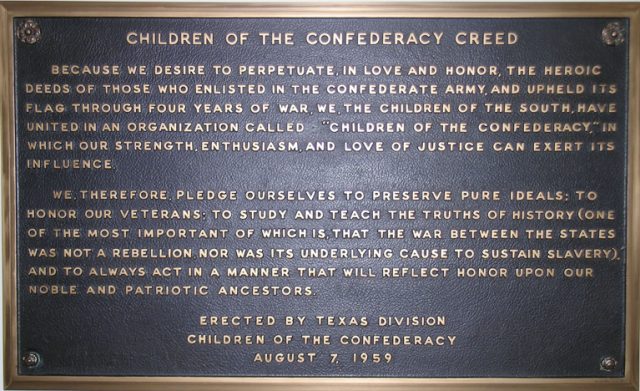

On Flags, Monuments, and Historical Myths

In response to student demand and in the wake of decisions made elsewhere in the southern U.S. to remove Confederate flags, UT-Austin President Greg Fenves appointed a Task Force to consider the removal of monuments to Jefferson Davis and other Confederate leaders that occupy a central site on the UT-Austin Campus.

Understanding history and separating historical analysis from historical myth is essential for any society. One of the many disturbing aspects of Dylann Roof’s murder of nine African Americans on June 17, is his justification of White supremacy on historical grounds. And one of the signs that we could be doing a better job as historians is the CNN poll that shows the majority of White Americans see the Confederate flag as a “symbol of southern pride” rather than a “symbol of racism.”

Over the next few weeks, Not Even Past will offer readers historical sources, readings, and commentary on these events. Last week, Mark Sheaves collected past articles devoted to the history of slavery and its legacy in the US and provided us with an annotated list.

Today we offer the historical analysis and commentary from journalists and historians primarily writing online. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter for more reading and news from the Task Force. (We will add to the list as relevant articles appear.)

First, “Causes Lost But Not Forgotten: George Washington Littlefield, Jefferson Davis and Confederate Memories at the University of Texas at Austin,” an article by Alexander Mendoza about the controversies that have dogged the statues since their inception.

“Monuments to Confederacy have their own History at Texas Capitol,” by Lauren McGaughy

Many southerners claim that Confederate flags and monuments are reflections of southern “heritage,” not racism. On the Nursing Clio blog, Sarah Handley-Cousins discusses the uses of heritage as a concept and a badge, “Heritage is Not History: Historians, Charleston, and the Confederate Flag.”

A 2011 Pew Research Center survey that showed that more people believe the Civil War was fought over states’ rights rather than over slavery.

In “Why Do People Believe Myths about the Confederacy? Because Our Textbooks and Monuments Are Wrong,” James W. Loewin addresses some of the ways southerners rewrote Civil War history in Texas and elsewhere.

To document the centrality of slavery to the reasons southern states went to war, Ta Nehisi-Coates wrote “What This Cruel War was Over,” arguing that “the meaning of the Confederate flag is best discerned in the words of those who bore it.”

(And in case you haven’t read Nehisi-Coates’ searing history of relentless White efforts to prevent Blacks from obtaining economic security, here it is: The Case for Reparations.)

Finally, Bruce Chadwick on one of the most pernicious, and successful, purveyors of myths about “the southern way of life,” D.W Griffiths’ Birth of a Nation, 100 years old this year.

Added July 8-9, 2015:

On discussing the commemoration of the confederacy with students:

David C. Williard, “I don’t want my students to simply choose sides in a polemic between heritage and hate.”

It’s complicated. Not very, but a little.

Richard Fausset, “‘Complicated’ Support for Confederate Flag in White South.”

Added July 14, 2015

Many people argue that removing monuments is erasing history:

Alfred L. Brophy, “Why Northerners should Support Confederate Monuments“

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

Another Perspective on the Texas Textbook Controversy

Recently, the Texas State Board of Education faced a firestorm of protest, from conservatives and liberals alike, over the statewide adoption of textbooks for teaching history. On November 21, 2014, the Board approved the use of 89 social studies textbooks. This vote was the culmination of a long and contentious debate about what to include in — and exclude from — textbooks. Some conservative groups thought the books’ content was “anti-American,” contending that publishers shortchanged America’s accomplishments. Specifically, they wanted more emphasis on the beneficial economic impact of the free market and the role of Christianity among the Founding Fathers. Others thought that the textbooks already contained a deeply conservative (and flawed) interpretation of the past. These critics warned that they distorted, exaggerated, and ignored some tough truths about the American past. In her testimony before the education board, Dr. Jacqueline Jones, the Chair of the History Department at the University of Texas at Austin, said, “We do our students a disservice when we scrub history clean of unpleasant truths and when we present an inaccurate view of the past that promotes a simple-minded, ideologically driven point of view.”

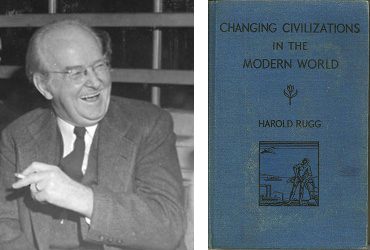

Public debate over the content of history textbooks goes back nearly 130 years, at least since the founding of the American Historical Association (AHA). In several reports in the 1890s, historians laid out a prescribed curricula for elementary and high school students. These initial reports received little criticism compared to what would come. Throughout the twentieth century, professors of history, teachers, parents, teacher educators, and other concerned citizens engaged in several high profile debates about the nature and purpose of history education in the nation’s public schools. One controversy from the 1930s about a popular textbook series created by Harold Rugg, a professor at Teachers College, Columbia University, provides historical context for what Texas just experienced in its debate over textbooks.

There are some similarities to the present-day — a struggling economy and calls for a more patriotic version of American history in our schools.The Great Depression and the Second World War witnessed dynamic curricular reform for history and social studies. After the stock market crashed in 1929, many Americans embraced what came to be called the social reconstructionist curriculum. Observing the consequences of capitalism run amok, Americans became more comfortable with curricula that not only critiqued economic inequality but also encouraged students to ask critical questions about the American past. Harold Rugg wrote his popular textbook series during the Depression.

Beginning in the late-1920s, Rugg began writing and publishing social studies textbooks centered on the question of “the American problem.” The textbook series was titled Man and His Changing Society, with individual titles like An Introduction to American Civilization, Changing Civilizations in the Modern World, and An Introduction to the Problems of American Culture. The textbooks focused on the economic and demographic growth of modern cultures and the development of decision-making skills. Rugg wanted junior high school texts to provide a comprehensive introduction to the modern world so that students could face the chief concerns that they would face as adults. Rugg’s textbooks opened with a dramatic historic episode, focused on key concepts, told dramatic stories, and included stimulating photos and cartoons. In addition, the textbooks raised serious questions about the nation’s social and economic institutions. This included critiques of unequal distribution of wealth and civil rights for African Americans..

The Great Depression’s horrible poverty helped Rugg’s social reconstructionist ideas gain prominence. Social reconstructionist curricula focused on the economic challenges facing the United States and the ways that schools could improve society. In 1933’s The Great Technology, Rugg called for “social engineering in the form of technological experts who would design and operate the economy in the public interest.” For Rugg, the challenge was to “design and operate a system of production and distribution which will produce the maximum amount of goods needed by the people and will distribute them in such a way that each person will be given at least the highest minimum standard of living possible.” George Counts, one of Rugg’s colleagues at Teachers College, expressed a similar view of education in 1932’s Dare the School Build a New Social Order? Counts pushed for a system of public education where teachers and students would critically examine America’s social institutions and chart solutions to the challenges that lay ahead.

As Rugg’s popular textbooks gained widespread use, a small group of influential conservatives challenged his social reconstructionist agenda. The bulk of criticism came from business journalists, retired military, and professional historians. Most of the criticism took place in New York and New Jersey. The fervor over Rugg’s textbook series led some school boards to censor the books or declare that they contained nothing subversive. As a result, Rugg’s accusers, many of whom Rugg debated face-to-face in public forums, were relatively unsuccessful at removing the textbooks from classrooms during the 1930s.

The 1940s were a different story, though. The Second World War brought a dramatic change not only in the minds of the public but also in what people wanted from history education. Instead of reading about how to improve American society, many people wanted their children to hear about what was right in American institutions. The United States was fighting a vicious two-front war against the Japanese Empire in the Pacific and Nazi Germany and its allies in Europe and North Africa. In the battle for hearts and minds against fascism, schools told students that it was honorable to give one’s life for American democracy. Social reconstructionist education was overtaken by patriotic education.

In order for a patriotic education to take root, Americans needed to know more U.S. History than what schools were teaching. In 1942, Allan Nevins, a professor of American history at Columbia University, wrote an article titled “American History for Americans” for the New York Times Magazine. Nevins believed that “young people are all too ignorant of American history.” He speculated that “the majority of American children never receive the equivalent of a full year’s careful work in our national history.” Nevins blamed schools and colleges. “Our education requirements in American history and government have been and are deplorably haphazard, chaotic, and ineffective,” he wrote. In 1943, the New York Times conducted a survey of 7,000 college freshmen at 36 colleges that seemed to confirm Nevins’ opinion. The findings found a striking “ignorance of even the most elementary aspects of United States history.”

After the Second World War, social reconstructionist educators faced more powerful opponents: anti-communist crusaders. The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) rounded up U.S. citizens suspected of communist ties. Professional educators feared for their jobs if they taught anything remotely critical in their American History courses. The risk of being labeled a communist was a serious threat. A few additional changes effectively killed the social reconstructionist movement. Under President Dwight D. Eisenhower, “under God” was added to the Pledge of Allegiance. This change reinforced the emerging understanding that the United States was not only a Christian nation but that it inhabited God’s chosen people. It was thus necessary to teach children that their Christianity was an asset against the godless communists in the Soviet Union, China, and elsewhere in the world. Then the U.S. economy rebounded after WWII. Consumer goods were more readily available. The average white citizen benefited from much better living conditions. Capitalism, it seemed, was proving that it offered many advantages over communism.

The early Cold War provided a climate for history education that has influenced the recent Texas history textbook controversy. U.S. citizens are still debating the role of Christianity in the nation’s history and whether elementary and high school students should learn the unpleasant truths that have been a part of America’s history. These different visions for history education will continue to divide politicians, professors of history, teachers, parents, teacher educators, students, and other concerned citizens in the years to come.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

Episode 69: The Amateur Photography Movement in the Soviet Union

In its early days, photography occupied an awkward middle ground between documentation and an art form, a debate which dragged on in the west for decades. The debate took place in the Soviet Union as well, where it was encouraged, discouraged, and then encouraged again in a roller-coaster of official policies between the eras of Lenin, Stalin, and Khrushchev. This interplay reveals a surprising amount about the lives of the artistically inclined Soviet middle class.

Guest Jessica Werneke has just completed her doctorate that looks at this oft-overlooked aspect of Soviet society, and discusses the turbulent world of amateur photography in the Soviet Union.

Gramsci on Hegemony

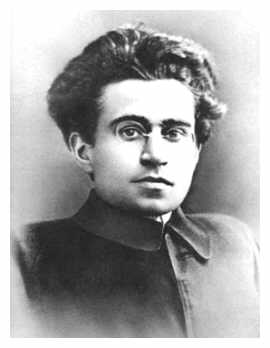

Antonio Gramsci was an Italian Marxist intellectual and politician who can be seen as the perfect example of the synthesis of theoreticians and politicians. He was not only a thinker involved in the revision and development of Marxism, who wrote in several socialist and communist Italian journals, but also a politically active militant. The fascist government of Benito Mussolini imprisoned him between 1926 and 1937.

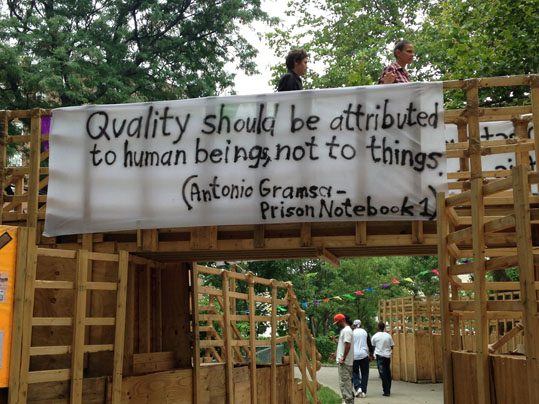

Gramsci’s political activities were not only related to his publications. His actions as a politician, activist, and intellectual were consistent with his ideas. He believed that the proletariat needed “organic” intellectuals (described below) to become a hegemonic class, and during his lifetime, he himself assumed such a role. As a member of the Socialist Party and, later, the Communist Party, he wrote in several journals seeking to reach a wide audience and indoctrinate it in the basic ideas and principles of the proletariat and social struggle. While incarcerated, and away from mass media, he wrote his most celebrated and influential theoretical contributions to Marxist theory. Among these, two concepts would become most important to scholars of different disciplines: hegemony and historical bloc. In what follows, this piece will concentrate on the concept of hegemony in Gramsci and the sources upon which he built it.

Gramsci developed the notion of hegemony in the Prison Writings. The idea came as part of his critique of the deterministic economist interpretation of history; of “mechanical historical materialism.” Hegemony, to Gramsci, is the “cultural, moral and ideological” leadership of a group over allied and subaltern groups. This leadership, however, is not only exercised in the superstructure –or in the terms of Benedetto Croce– is not only ethico-political, because it also needs to be economic, and be based on the function that the leading group exercises in the nucleus of economic activity. It is based on the equilibrium between consent and coercion. Gramsci first noted that in Europe, the dominant class, the bourgeoisie, ruled with the consent of subordinate masses. The bourgeoisie was hegemonic because it protected some interests of the subaltern classes in order to get their support. The task for the proletariat was to overcome the leadership of the bourgeoisie and become hegemonic itself.

Although for some scholars the Gramscian concept of hegemony supposes the leading role of the dominant class in the economy, Gramsci believed that the leading role of the dominant class must include ideology and consciousness, that is, the superstructure. The location of cultural, ideological, and intellectual variables as fundamental for the proletariat in its struggle to become a leading class is Gramsci’s main contribution to Marxist theory. With it, the Italian intellectual sought to undermine the economic determinism of historical materialism. He was acknowledging that human beings had a high degree of agency in history: human will and intellect played a role as fundamental as the economy.

Even though Gramsci was harshly critical of what he called the “vulgar historical materialism” and economism of Marxism, as a Marxist he assumed the fundamental importance of the economy. At this point, however, economic determinism seems to be a problem for the Gramscian concept of hegemony, and the ways the proletariat can become hegemonic. According to Gramsci, only a hegemonic group that has the consent of allies and subalterns can start a revolution, which would mean that it is necessary to establish proletarian hegemony before the socialist revolution.

However, how can the proletariat have a dominant position in the world of economy before the socialist revolution? How could the proletarians dominate the economy if the bourgeoisie is the class that controls the means of production and, therefore, controls the economy? Here Gramsci proposes that, in order to achieve a hegemonic position, the proletariat must ally with other social groups struggling for the future interests of socialist society, like the peasantry. The idea was to establish a new historical bloc (one that breaks the order established by the capitalist structure and the political and ideological superstructures on which the bourgeoisie relies) and a new collective will of the subaltern classes. This, in words of Im Hyug Baeg, can be interpreted as “counter-hegemony” something that “is not a real hegemony in strict sense, but economic, political and ideological preparations for hegemony before overthrowing capitalism or before winning state power” (Hyug Baeg, 142).

One of the ways the proletariat must undertake such a task is through “organic intellectuals,” which for Gramsci, “are the dominant group’s ‘deputies’ exercising the subaltern functions of social hegemony and political government.” Their “function in society is primarily that of organizing, administering, directing, educating or leading others.” These specialized cadres, formed both in the working-class political party and through education, had the duty of organizing, administering, directing, educating or leading others. The formation of a national-popular collective is not an autonomous process, nor is the will of that collective. The organic intellectuals, who must be unrelated to the intellectuals of the bourgeoisie, must organize and mediate in the formation of the national-popular collective will.

Sources and Further reading:

Antonio Gramsci, The Antonio Gramsci Reader, eds. David Forgacs and Eric Hobsbawm (New York: NYU Press, 2000).

Carlos Emilio Betancourt, “Gramsci y el concepto del bloque histórico”. Historia Crítica. Julio-Diciembre 1990, pp. 113-125.

Derek Boothman, “The Sources for Gramsci’s Concept of Hegemony,” Rethinking Marxism: A Journal of Economics, Culture & Society (2008), 20:2, pp. 201-215.

Im Hyug Baeg, “Hegemony And Counter-Hegemony In Gramsci.” Asian Perspective, Vol. 15, No. 1 (Spring-Summer 1991), pp. 123-156.

Gramsci Monument, Bronx, New York

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.