In each of my graduate seminars, at the beginning of the semester, I caution students not to use certain words I consider problematic; these words can actually hinder our understanding of a complex past. Commonly used—or rather, overused—in everyday conversation as well as academic discourse, the banned words include “power,” “freedom,” and “race.” I tell my students that these words are imprecise—they had different meanings depending upon the times and places in which they were used– and that today we tend to invoke them too casually and even thoughtlessly.

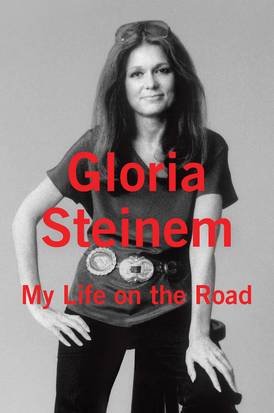

Oh yes, and there is another word I ask my students to avoid—“feminism.” Students often greet this particular injunction with surprise and dismay. Does it mean that their instructor believes that women should stay at home and not venture into the paid labor force? If so, why is she standing in front of a classroom now? So I have to be sure to make a case about the pitfalls related to the use of the word. Even the broadest possible definition is problematic, as we shall see.

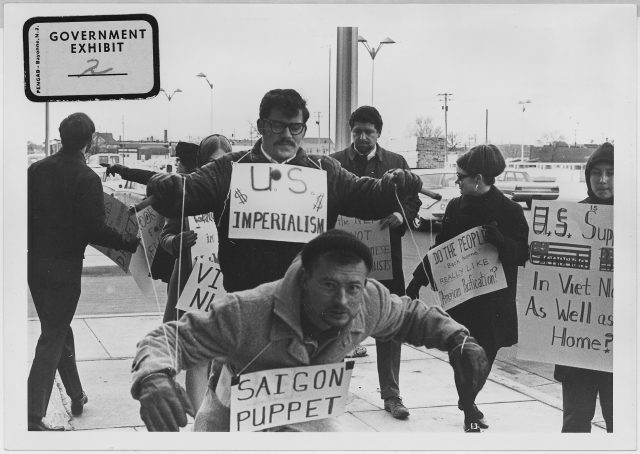

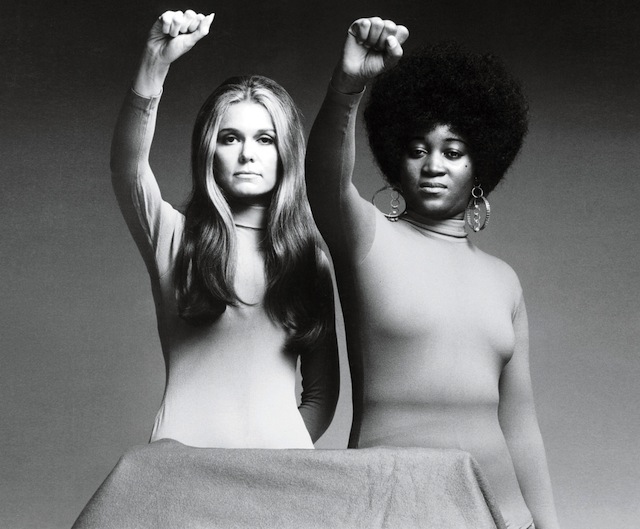

The purpose of the massive march on Washington held on January 21, the day after President Trump’s inauguration, was to protest his election. It was called the “Women’s March,” and as we all know, sister marches took place all over the country and the world the same day. A group of women initiated the idea of the protest, and took care of all the logistics; many participants wore pink “pussy hats” to call attention to the President’s demeaning remarks about grabbing women’s genitals captured on the infamous Access Hollywood videotape. The hand-held signs at the rally covered a whole range of issues, including abortion and reproductive rights, equal pay, sexual harassment, Black Lives Matter, protection for undocumented immigrants, public education, and women’s struggles for fair treatment and equality generally. Presumably, Trump’s election had prompted an historic level of anger and frustration among women. Many news outlets, participants, and observers suggested that the march represented a remarkable display of re-energized, twenty-first century feminism, with the word itself suggesting a kind of transcendent womanhood bringing together women of various ages, races, classes, and ethnicity.

Well, not exactly. Although only 6 percent of African American women voted for Trump, 53 percent of white women did. We can safely assume, then, that many white women not only stayed away from the march, but also objected to it in principle: the pink-pussy-hat contingent did not speak for them. So we might ask, which groups of women did not march? Here is a possible, partial list: devout Catholic women who believe that birth control, abortion, and gay marriage are sins against God; former factory workers who were fired from their jobs when their plants were shipped overseas; the wives and daughters and mothers of unemployed coal miners; anti-immigrant activists; women of color who saw the march as dominated by white women; and pro-gun rights supporters. Missing too were probably women who found Mr. Trump’s video sex-talk disgusting but chose not to see this as the defining issue in the 2016 Presidential campaign–just as some liberal women might have disapproved of Bill Clinton’s affair with Monica Lewinsky but did not let that affair diminish their support for him when he was president. In both these cases, the pro-Trump and pro-Clinton supporters expressed less solidarity with the men’s victims and more support for other elements of the men’s politics. In other words, these women eschewed any putative “sisterhood” in favor of other political issues.

Another way of looking at this issue is to challenge the view that feminists had as their greatest priority a woman president. How many self-identified feminists were eager to see Sarah Palin run for president in 2012? Again, for many women, their overriding concern is not womanhood per se but a wide range of political beliefs and commitments. As we learned soon after U. S. women got the right to vote in 1919, different groups of women have different politics; in the 1920s, the suffragists were astonished to find that women tended to vote the way their husbands did, according to a matrix of ethnic and class factors.

Delegation of officers of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, 1917 (US National Archives via Flickr).

The example of the Women’s March suggests that, for all the talk today of “intersectionality” (the interconnectedness of certain social signifiers such as class, religion, “race,” and gender) “feminism” promotes a very specific political agenda, one that does not necessarily reflect the priorities and lived experience of a substantial portion of the female population. In essence, the word “feminism” is too vague to have much meaning within a society where women have multiple forms of identity, and gender might or might not be the defining one at any particular time. Even the broadest possible definition—feminists are people who seek to advance the interests or the equal rights of women—has its limitations.

As an historian, I would suggest several reasons why students should avoid the use of the word “feminism”–unless they encounter the word in a primary text; then they should try to figure out what the user meant by it.

- The word itself did not appear in common usage until the 1920s. Therefore it would be a mistake to apply it to people before that time, or to people since who themselves have not embraced the label; otherwise we risk imposing a term on historical actors who might or might not have used it to describe themselves.

- Throughout history, various waves of the so-called “women’s” or “feminist” movement were actually riven by intense conflicts among women. Around the turn of the twentieth century, leading white suffragists went out of their way to denigrate their black counterparts and express contempt for immigrant and working class men and women. The early organizers of the National Organization for Women feared that association with lesbians and militant black women would taint their drive for respectability. Organizers of the 2017 Women’s march debated whether or not anti-abortion women could or should be included in the protest: could one be a feminist and at the same time oppose reproductive rights for women?

- Often in history when we find solidarity among women it is not because these groups of women sought to advocate better working conditions or the right to vote for all women; rather, their reference group consisted of women like themselves. In the 1840s, Lowell textile mill workers walked off the job and went on strike not as “feminists,” but as young white Protestant women from middling households—in other words, as women who had much in common with each other. Religion, ethnicity, lineage, and “race” have all been significant sources of identity for women; when a particular group of women advocates for itself, it is not necessarily advocating for all other women.

- Similarly, we are often tempted to label those strong women we find in history as “feminists,” on the assumption that they spoke and acted on behalf of all women. Yet they might have believed they had more in common with their male counterparts than with other groups of women. Female labor-union organizers probably felt more affinity with their male co-workers than with wealthy women who had no experience with wage work. In other words, the transcendent sisterhood that feminism presupposes is often a myth, a chimera.

- The word not only lacks a precise definition, it also carries with it a great deal of baggage. Indeed, some people have a visceral, negative reaction to the sound of it. It is difficult to use a term with such varied and fluid meanings. And feminism meant something different to women of the 1960s, when they could not open a credit-card account in their own name or aspire to certain “men’s jobs,” when they debated the social division of labor in the paid workplace and in the home, compared to young women today, who at times see feminism through the prism of music lyrics, movies, fashion, and celebrity culture: Is the talented, fabulously wealthy Taylor Swift a feminist?

- Finally, a personal note: In the 1960s, I was a college student and caught up in what was then called the “feminist movement” as shaped by Betty Friedan’s book The Feminine Mystique and the newly formed National Organization for Women. My mother disapproved of my emerging priorities in life; she had gotten married right after World War II, and she believed (rightly, as it turned out) that the movement denigrated her choice to stay home full-time with her children. I was puzzled and distressed that my mother could not appreciate my choices; but now I am also puzzled and distressed that the movement could not appreciate her choices. Coming of age during the war, she feared that she would never marry and have a family, and when she finally had that opportunity, she was happy—for the most part—to embrace it, despite the considerable financial sacrifice for the household that her choice entailed.

Women’s March 2017 (Backbone Campaign via Flickr).

Perhaps, with very few exceptions—equal pay for equal work?—there are few issues on which all women everywhere can agree. My own view is that, we can pursue social justice in ways that advance the interests of large numbers of men as well as women, without having to defend the dubious proposition that “feminism” as constructed today speaks to and for all women. It doesn’t. For the historian, that fact means that we have to come up with other, more creative ways of discussing forms of women’s activism and personal self-advancement that took place in the past, and, in altered form, continue today.

![]()

Also by Jacqueline Jones on Not Even Past:

The Works of Stephen Hahn.

On the Myth of Race in America.

History in a “Post-Truth” Era.

![]()