Gauri Viswanathan provides a fascinating account of the ideological motivations behind the introduction of English literary education in British India. She studies the shifts in the curriculum and relates such developments to debates over the objectives of English education both among the British administrators, as well as between missionaries and colonial officials.

Viswanathan argues that British administrators introduced English literary study in India in the early nineteenth century to improve the moral knowledge of Indians. Since Britain professed a policy of religious neutrality, Christian teachings could not be used in India, unlike the situation in Britain. In order to resolve this dilemma, colonial officials prescribed English literature, infused with Christian imagery, for government schools. Initially, Indians studied English literature using poetical devices, such as rhyme, alliteration, and reduplication. However, missionaries decried such secular practices and insisted upon a more religious reading of English literature. As a result, between 1830s and the mid-1850s, government schools in India used English literature to explain Christian teachings and emphasize the higher levels of historical progress and moral standards of English society. By the end of the 1850s, however, British administrators again changed their stance and advocated a secular reading of English literature to encourage commercial and trade literacy. This reversal of stance occurred as British officials realized that a religious reading of English literature did not provide Indians with the proper knowledge to join the colonial administrative services. Besides, after the 1857 Indian revolt against foreign rule, British officials did not wish to adopt policies that might ignite fears of conversion among Hindus and Muslims.

Viswanathan gives a detailed account of the various debates that influenced the introduction of English literary study in India. While she minutely examines the stances of Utilitarians, Anglicists, and missionaries, the absence of chronological benchmarks at regular intervals prevents the reader from fully understanding the shifts in education policies in British India emerging from such debates. However, her work changes our way of studying British educational policies in India. Previously, scholars merely studied the transformative effects of British education to understand the historical function of educational policies. Viswanathan ably proves that it is necessary to examine the discourse and the context of the formulation of educational policies to better understand educational history.

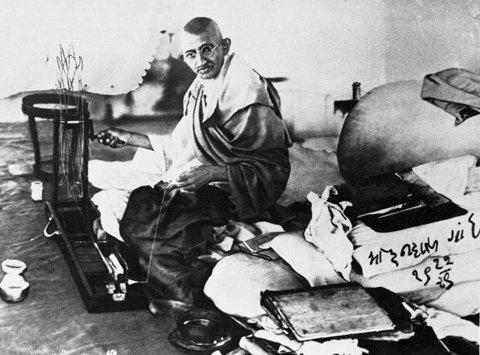

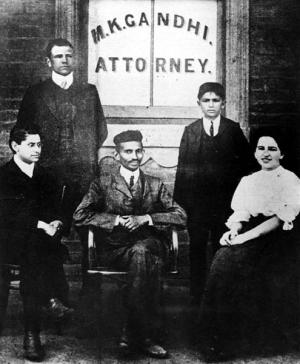

Photo Credits:

All photos courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

by

by

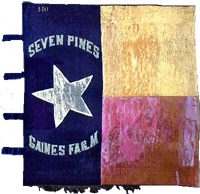

The “Ragged Old First” lost their regimental colors as well. Historian

The “Ragged Old First” lost their regimental colors as well. Historian