On December 8, 2011, newspapers in Zimbabwe – and Zimbabwe’s diasporas – reported that an unmarked tree in the middle of a busy street in the capital, Harare, had been accidentally knocked down by a city council van. The tree made headline news because urban lore has it that it was the tree upon which “Mbuya Nehanda” (Charwe wokwa Hwata), the late nineteenth-century spirit medium, was hanged by British colonial authorities. Historical evidence holds otherwise, but scholarly and popular debates on Nehanda-Charwe attest to the vigor of her connection with this tree and her larger place in history.

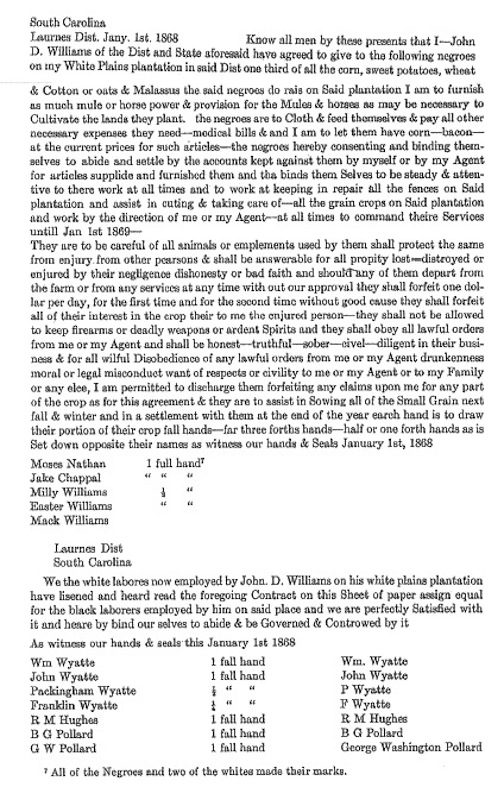

Sekuru Kaguvi and Mbuya Nehanda after capture, 1897.

Charwe wokwa Hwata was born in about 1862, and was medium to a revered female spirit of rain and land fertility, the spirit of Nehanda. She is called Nehanda or Mbuya Nehanda for much the same reasons Tenzin Gyatso is called the Dalai Lama. Charwe participated in the 1896-97 uprising against British colonialism in central Zimbabwe, and became a British symbol for the need to “civilize” the Africans. The memory of Nehanda-Charwe in the history of Zimbabwe dates back to 1898 when she was executed. In the 1950s, Charwe (as Nehanda) became a symbol for African Nationalists of the “uncolonized” past that had been destroyed by colonialism. During the anticolonial, liberationist wars of the 1960s-70s, her image was recruited as spiritual guide and nationalist symbol as evidenced by this song from that period.

The song begins:

Mbuya Nehanda died truly wondering

‘How shall we take [back] this land?’

The one word she told us was

‘Seize the gun and liberate yourselves.’

The song is itself fascinating for its blend of history (1896-97) and memory (1960s-70s), as Nehanda became at once an old ancestor, and a current guerrilla fighter, a theme I explore more fully in my book.

What has been fascinating about the recent story of the “Nehanda tree” is not so much the felling of an old tree in the city, but the interpretations of reporters, bloggers, eyewitnesses, and anyone who can access the internet to comment on those news stories and blogs. On my most recent trip to Zimbabwe, in December 2011, friends and family told me about the “tragedy” of Nehanda’s tree in whispers, lamentation, argumentation, and the gamut of expressions much like those found online. The response to the story of Nehanda’s tree knocked over by a mere city council van, are most fascinating because of what they say about the animation of personal and social memories in particular moments in history. This incident has brought to the surface memories of colonialism, conflicts over religion, and especially angst about the present as people graft meaning onto the knocked down tree as representing a turning point (for better and/or worse) for Zimbabwe from here on out. News about this tree and memories of the woman associated with it have raised tensions today because she is seen as a symbol of the hopeful, anti-colonialist guerilla movement of the 1960s-1970s, whose elites have turned into ruthless rulers blinded by the corrupting nature of political power.

The story of the “Nehanda tree” shows that the socio-cultural and political meaning of the symbol of Charwe as “Mbuya Nehanda” vigorously rubs history and memory against each other in Zimbabwe to produce doubts about her place in history, faith that she (her spirit, that is) is still very present and is trying to say something to the country, especially its leadership, Christian inflected attacks on what she stood for (African forms of religious power and spirituality), as well as the need to honor a woman who made it into the history books when so many African women of the past have gone the way of seeds in the wind that land in the desert never to be remembered.

The meaning of this song today – much like the reports and comments on the dead tree – is connected to the ways that the past is grafted onto the present. The “tree of Nehanda,” reveals some of the ways people exercise their citizenship, protesting (and/or supporting) the current state of affairs that are incongruent with “Mbuya Nehanda” the symbol of anti-colonialism turned matron saint of a now unacceptable regime that has reneged on what she died for: the promise of full independence made in 1980 when the country’s black majority gained civil rights in the country of their birth. The reports and comments on “the tree of Nehanda” speak to the ways societies shake the tree of history in order to find meaning in the past.

Translation of the song about Mbuya Nehanda can be found in Songs that Won the Liberation War by Alec J.C. Pongweni

The debates on Zimbabwe are ongoing, see among others:

Ruramisai Charumbira “Nehanda and Gender Victimhood in the Central Mashonaland 1896-97 Rebellions: Revisiting the Evidence” History in Africa,35 (2008)

Mahmood Mamdami, “Lessons of Zimbabwe,” London Review of Books

Scholars discuss Mamdami’s “Lessons,” Concerned Africa Scholars

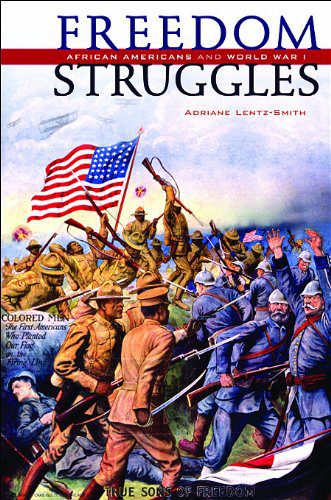

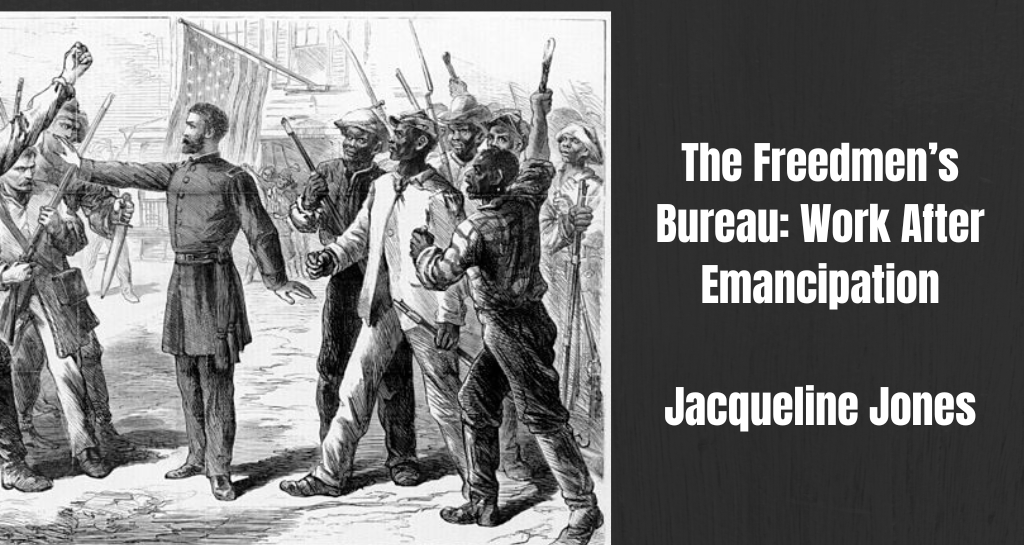

Together, both books also offer a rich counter-narrative to traditional World War I history. By eschewing the classic topics associated with the subject, namely German nationalism and the heroism of white American soldiers and politicians, Lentz-Smith and Williams write the black soldier out of the margins and recount the wartime experience largely from his perspective.

Together, both books also offer a rich counter-narrative to traditional World War I history. By eschewing the classic topics associated with the subject, namely German nationalism and the heroism of white American soldiers and politicians, Lentz-Smith and Williams write the black soldier out of the margins and recount the wartime experience largely from his perspective.

Torchbearers for Democracy, reiterates some of the major themes found in Freedom Struggles. Williams, like Lentz-Smith, probes black soldiers’ beliefs that military service would lead to a quicker acknowledgment of their citizenship and manhood rights. After all, military service has long been a vehicle for white men to prove their loyalty and fitness for American citizenship, so in the minds of many of black soldiers, the same formula had to work for them. Yet, Williams maintains that a bulk of the black soldier’s work would have to be performed at home since it was here that Jim Crow proved an unrelenting combatant. Williams offers a poignant chapter on how black veterans navigated the intensely violent summer of 1919, known as “Red Summer.” He also reveals the numerous ways in which black soldiers and veterans fought to end racial inequality in practically every area of American life—from politics to labor. Williams also reflects on the role of black soldier in history and memory, ultimately arriving at some original and insightful claims regarding the notions of internationalism and diaspora.

Torchbearers for Democracy, reiterates some of the major themes found in Freedom Struggles. Williams, like Lentz-Smith, probes black soldiers’ beliefs that military service would lead to a quicker acknowledgment of their citizenship and manhood rights. After all, military service has long been a vehicle for white men to prove their loyalty and fitness for American citizenship, so in the minds of many of black soldiers, the same formula had to work for them. Yet, Williams maintains that a bulk of the black soldier’s work would have to be performed at home since it was here that Jim Crow proved an unrelenting combatant. Williams offers a poignant chapter on how black veterans navigated the intensely violent summer of 1919, known as “Red Summer.” He also reveals the numerous ways in which black soldiers and veterans fought to end racial inequality in practically every area of American life—from politics to labor. Williams also reflects on the role of black soldier in history and memory, ultimately arriving at some original and insightful claims regarding the notions of internationalism and diaspora.

Sometimes this portion inexplicably involves a swimming race. Watching my grad student colleagues finish up their exams as they prepare to leave for dissertation research has sparked a few memories, so I thought I’d write about comps so that people have a sense of what it is that most third-year grad students do all year.

Sometimes this portion inexplicably involves a swimming race. Watching my grad student colleagues finish up their exams as they prepare to leave for dissertation research has sparked a few memories, so I thought I’d write about comps so that people have a sense of what it is that most third-year grad students do all year.