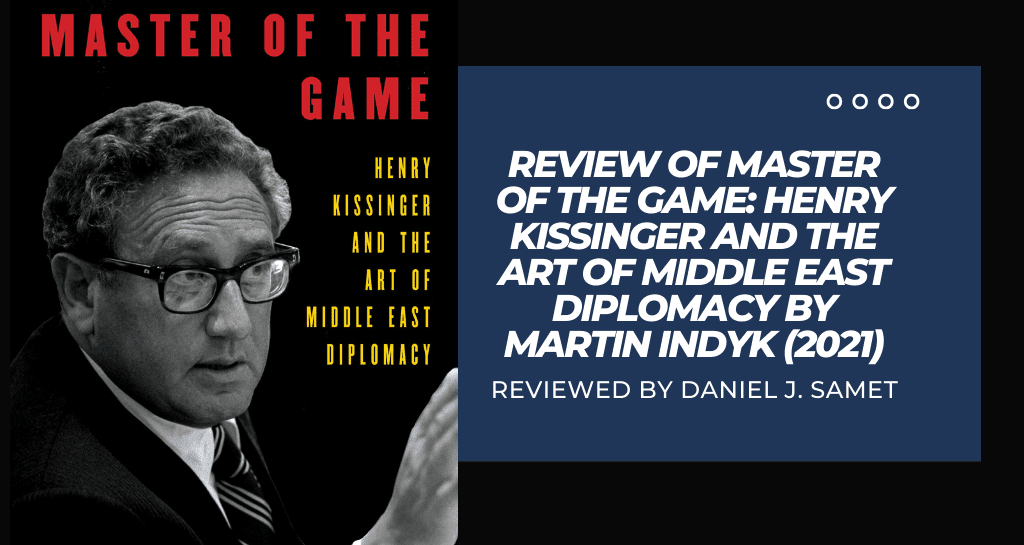

This is no ordinary work of history. That’s a good thing. As opposed to many scholarly studies, this book has an author with real-world experience in his field. Martin Indyk, who served as U.S. Ambassador to Israel and Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs under Clinton and Special Envoy for Middle East Peace under Obama, knows the Middle East like the back of his hand.

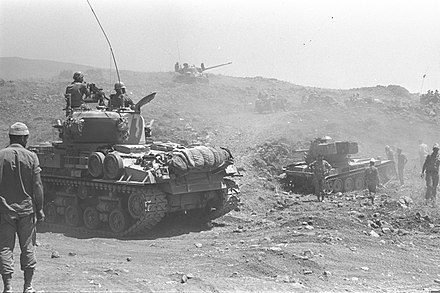

The same could not be said of his biographical subject before the Yom Kippur War. While orchestrating détente with the Soviet Union and an end to America’s presence in Vietnam, Henry Kissinger had his mind elsewhere and spared few thoughts for the Middle East. But that changed abruptly when Israel and its Arab foes took up arms once again in October 1973.

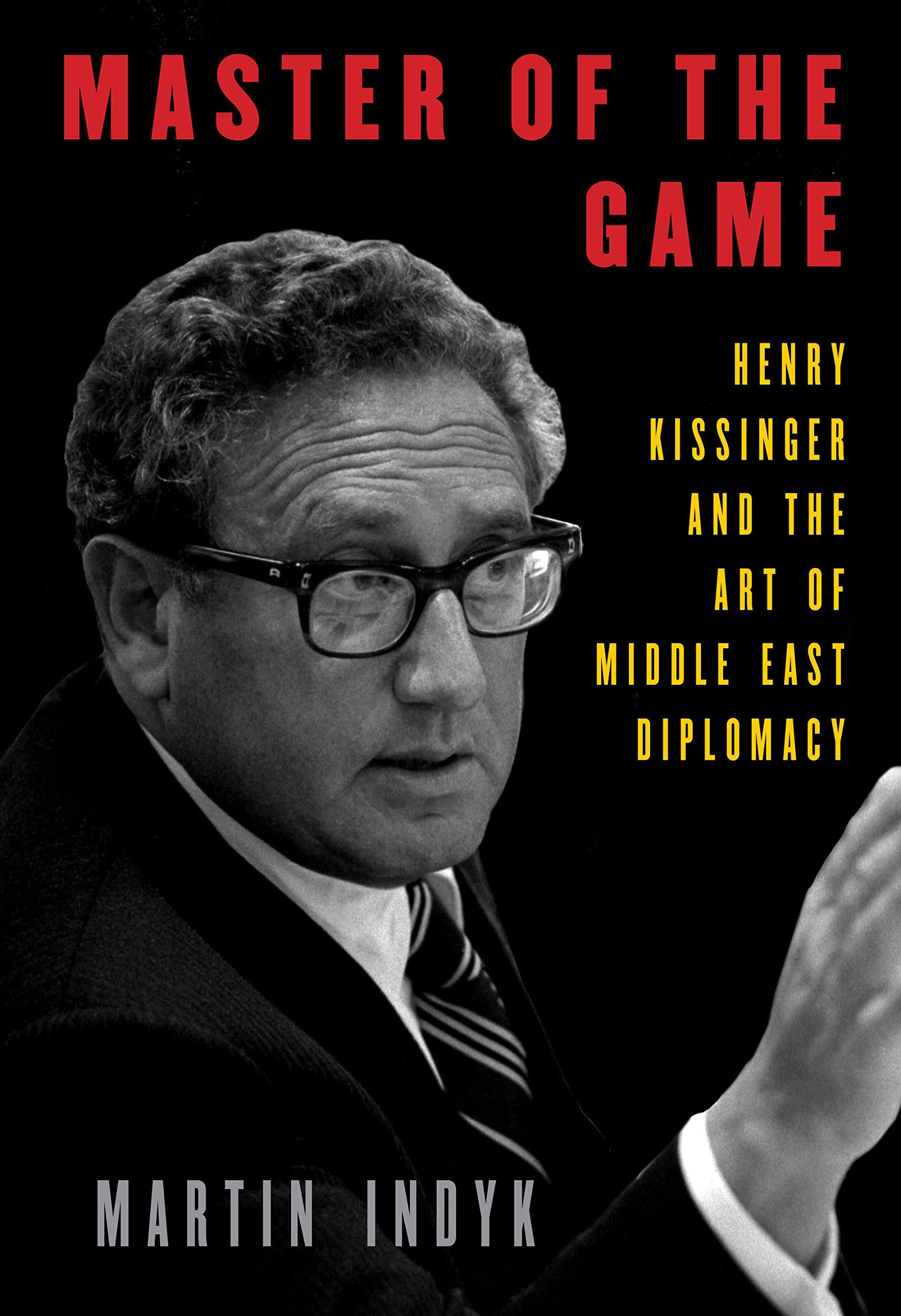

Thereafter Kissinger went above and beyond in his regional outreach. Master of the Game documents how over the next two years, the secretary of state held many meetings with Arab and Israeli interlocutors in seeking a lasting peace. From his shuttle diplomacy came a string of disengagement agreements: two between Israel and Egypt and one between Israel and Syria. In Kissinger, Indyk sees a brilliant practitioner of statecraft whose pragmatic, incremental approach succeeded where others had failed.

Driving Kissinger’s relentless diplomacy was a particular vision for the Middle East. This vision, argues Indyk, modeled itself on the order Metternich, Castlereagh, and Talleyrand forged for post-Napoleonic Europe (the subject of Kissinger’s dissertation-cum-monograph A World Restored). The question of whether a bespectacled academic well-versed in European statecraft could apply his wisdom to the Middle East was soon answered.

Although Indyk is mainly interested in American decision-making, Arab and Israeli officials are not mere bystanders in his story. He writes at length about how the likes of Ismail Fahmy, Yitzhak Rabin, and Hafez al-Assad sized Kissinger up, not just the other way around. No number of American carrots and sticks could make both sides come to terms with one another. Those were decisions they alone could make. Present and prospective policymakers should bear in mind that however strong the United States may be, Middle Eastern countries can always push back.

Indyk shares lessons he has drawn from Kissinger’s accomplishments. One of these is the role of domestic politics. In the United States, Kissinger faced pressure from pro-Israel voices to be as generous as possible toward the Jewish state. Israel witnessed a premiership change during the period in question (due to Golda Meir’s perceived weakness) and had many constituencies to placate. The Egyptian and Syrian governments were not democratic but nonetheless were mindful of public opinion.

Some of the strongest lessons are those unique to Israeli-Palestinian peacemakers. As Indyk observes, Washington cannot make things happen on its own. All the more so when it eagerly pushes Arab and Israeli officials to the negotiating table where “a sense of urgency is often absent” (304). The fact that Americans are keen to strike deals does not mean Arabs and Israelis are.

Although he does not deify Kissinger, Indyk risks overstating his importance. Kissinger clearly played an important role in bringing Arabs and Israelis together and negotiating the details of their agreements, but is it fair to anoint him “Master of the Game?” Calling him as much masks Kissinger’s considerable shortcomings in his shuttle diplomacy.

These are shortcomings that Indyk acknowledges. For instance, Kissinger’s ignorance of Middle Eastern politics made him “underestimate the importance of the Palestinian issue in the legitimation of his American-led order” and sideline King Hussein and the Jordanians when they could have been invaluable peace brokers (554). Kissinger’s amoral realism left little room for matters beyond power politics, but he would learn the hard way that Arab leaders were willing to go to the mat for the Palestinians.

That realism was the only reason why Kissinger was in the Middle East in the first place. In facilitating these Arab-Israeli negotiations, he sought to wrest Egypt, and to a lesser extent Syria, from the Soviet sphere. In so doing, he also hoped to create a stable balance of power that would avert wars like the one in 1973.

Ultimately, Israel grew strong enough to resist pressure to give concessions to Arab adversaries, and it has neither concluded a peace treaty with the Syrians nor a final-status agreement with the Palestinians. Yet Indyk shows convincingly that Kissinger did not intend for Israel to turn into the regional superpower it became. Such an outcome was discordant with his Metternechian worldview and did not redound to his goal of making Egypt and Syria centerpieces in a new U.S.-aligned Middle East. Then as it does now, self-interest mainly explained America’s presence in that far afield place.

For all of Indyk’s criticisms of Kissinger, his admiration of the man is palpable. Indyk’s service in two administrations that failed to achieve a final Israeli-Palestinian peace deal has helped him appreciate how extraordinary Kissinger’s diplomatic accomplishments in this part of the world were. As Indyk shows in Master of the Game, negotiation, and diplomacy require considerable skill.

Those at odds with Indyk’s methodological approach might say he gives too much importance to Kissinger the individual. Why not give credit to the legions of government staff and civil-society actors who worked so hard to make these agreements happen? Does Kissinger truly deserve the star billing he gets? These are genuine questions, but, in my view, the choice to make Kissinger the central figure in this story stands up to scrutiny. Arab and Israeli leaders negotiated through him. No one else spent more time in conversation with them or diplomatic capital in bringing both sides together. Kissinger undoubtedly was the sine qua non.

On a separate note, this book puts the lie to charges that the United States has given Israel whatever it wants. To the contrary, there is ample evidence of U.S.-Israel friction. The Israeli side often frustrated Kissinger. The barbs traded with Prime Minister Golda Meir could be ferocious. She could not believe a fellow Jew could be so dismissive of Israel’s security interests, while he resented Israeli intransigence. Under Rabin’s government, too, the Americans and Israelis gave each other an earful over seemingly minute details. Thanks to plentiful American and Israeli sources, Indyk makes exchanges like these lively and engaging. In this way, Master of the Game is the latest installment in a literature that has cast the U.S.-Israel relationship as one of tension and compromise rather than harmony. See Dennis Ross’ Doomed to Succeed: The U.S.-Israel Relationship from Truman to Obama (2015) for another example.

Evidence in the book should also dispel the view that Kissinger was heartless. On his way out of Israel without a peace treaty in March 1975, Kissinger started crying after declaring “we have no other goal except to enable the young people in this area to grow up without the fear of war” (478). While he has been criticized for his alleged callousness, this book shows that Kissinger, albeit unwaveringly devoted to his craft, was not immune to emotion.

Those who’ve had enough of America’s misbegotten adventures in the Middle East might be tempted to skip this book. That would be their loss. Master of the Game tells the story of an overall successful policy of negotiation. A superpower got many of its sought-after objectives by engaging a handful of middle powers. As great-power rivalry returns to Asia, Europe, and elsewhere, American policymakers would do well to learn from Kissinger’s example.

In telling a remarkable story, Master of the Game proves it is possible to write well without sacrificing scholarly standards. The book includes its fair share of colloquial gems—Israeli Defense Minister Moshe Dayan “sounded like an excited bro planning a fraternity party” while talking to Kissinger, we’re told (256). Forgoing the heavy prose that can mar academic writing, Indyk makes this book accessible to the lay reader. That might be a function of his time in the government, where it pays to shun the abstract for the concrete.

At the same time, Indyk’s book is firmly grounded in historical evidence. Among the archives Indyk consults are the Nixon and Ford Presidential Libraries, the Department of State’s Office of the Historian, and the Israel State Archives. He gives the sources their due. Policymakers in search of historical background and practical advice would do well to read this book. Inside they will find a road map for remedying seemingly intractable disputes, not only in the Middle East but perhaps in the world beyond.

Daniel J. Samet is a Ph.D. student in History at the University of Texas at Austin, where he is a Graduate Fellow at the Clements Center for National Security.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.