By Edward Shore

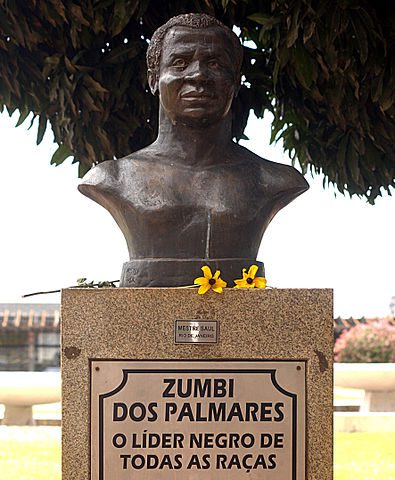

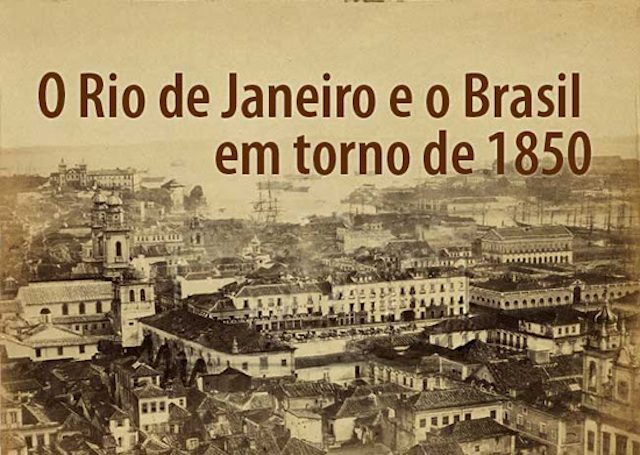

In November 1695, townspeople in Recife, Brazil, observed Portuguese soldiers attaching a severed head to a stake in the central plaza. The skull belonged to Zumbi, the last warrior-king of Palmares, a “quilombo,” or fugitive slave community, hidden in the rugged backcountry of the Brazilian Northeast. Palmares was home to twenty thousand runaway slaves, free blacks, Indians, and settlers of mixed ancestry who repelled the repeated assaults of European slavers for almost a century. Although the Portuguese managed to defeat Zumbi’s guerrillas, memories of Palmares evolved into myths that powerfully shaped Brazilian politics and popular culture. They fanned the flames of slave resistance and inspired future generations of black activists and intellectuals who challenged racism, capitalism, and military rule in modern times.

Glenn Cheney’s new book, Quilombo dos Palmares: Brazil’s Lost Nation of Fugitive Slaves, retraces the maroon community’s origins and casts new light upon the lived experiences of its diverse inhabitants. Drawing upon a range of colonial documents and secondary sources, Cheney advances a number of compelling claims about the nature of Palmares and its century-long struggle for survival. First, he argues that the quilombo represented a viable alternative to plantation slavery and Portuguese colonialism. Fugitive slaves established a collective economy based upon subsistence agriculture, trade, and communal land ownership. They raided plantations and sugar mills in search of new supplies and recruits. Palmarians rejected Portugal’s rigid caste system and mixed freely with Africans, crioulas (Brazilian born blacks), mulattos, Indians, and even poor whites. The author also suggests that women were socially, economically, and militarily empowered and that marriage and sexual morality were established by “necessity and efficiency” rather than by religious edict. Religion in the quilombo was syncretic, an amalgamation of beliefs and practices pulled together from Bantu (Central African), indigenous, and Catholic traditions.

Glenn Cheney’s new book, Quilombo dos Palmares: Brazil’s Lost Nation of Fugitive Slaves, retraces the maroon community’s origins and casts new light upon the lived experiences of its diverse inhabitants. Drawing upon a range of colonial documents and secondary sources, Cheney advances a number of compelling claims about the nature of Palmares and its century-long struggle for survival. First, he argues that the quilombo represented a viable alternative to plantation slavery and Portuguese colonialism. Fugitive slaves established a collective economy based upon subsistence agriculture, trade, and communal land ownership. They raided plantations and sugar mills in search of new supplies and recruits. Palmarians rejected Portugal’s rigid caste system and mixed freely with Africans, crioulas (Brazilian born blacks), mulattos, Indians, and even poor whites. The author also suggests that women were socially, economically, and militarily empowered and that marriage and sexual morality were established by “necessity and efficiency” rather than by religious edict. Religion in the quilombo was syncretic, an amalgamation of beliefs and practices pulled together from Bantu (Central African), indigenous, and Catholic traditions.

Second, Cheney contends that Palmares functioned like a sovereign state. He observes that the quilombo was not, at least initially, a single political entity, but rather a collection of mocambos (“hideouts”) that stretched across a territory that was two hundred miles long and fifty miles inland from the coast of what is today the Brazilian state of Alagoas. Ultimately, these communities recognized a common enemy, the Portuguese, and integrated the various mocambos into a unified military brotherhood. Inhabitants elected village leaders to a council and the council selected a head of state. There is also evidence to suggest the Portuguese monarchy had recognized the quilombo’s autonomy and even attempted to broker a truce between planters and maroons in the 1670s.

Cheney concludes that Palmares grew strong enough not only to frustrate, but also to seriously challenge Portuguese control of Brazil. Following the decline of sugar production and the Dutch invasion of Pernambuco, Zumbi and his army of fugitive slaves threatened to deliver a crushing blow to Portugal’s fragile colonial ambitions. Cheney alleges that Palmares signaled the beginning of a long-term movement toward independence from colonial rule and foreshadowed the rise of Toussaint L’Overture and the “Black Jacobins” in Haiti. The Portuguese, though weakened, resolved to destroy the quilombo. Armed with an influx of capital, weaponry, and manpower from Lisbon and São Paulo, colonizers assembled an army of mercenaries, Indians, and slaves that sacked Palmares in 1693 and captured and executed Zumbi two years later.

However, the destruction of Palmares failed to stem the emergence of hundreds, perhaps thousands of smaller quilombos throughout Brazil. Nor did it prevent countless other acts of resistance that undermined planter domination even after the abolition of slavery in 1888. Cheney describes how the legend of the Quilombo dos Palmares inspired a 1988 constitutional amendment that extended land rights to the descendants of fugitive slaves. Thousands of “modern quilombos” have petitioned for government recognition while organizing mass movement in the countryside that has won concessions from local landowners and pressured elected officials to implement affirmative action policies in other areas. In 2015, the specter of Palmares looms large over Brazil.

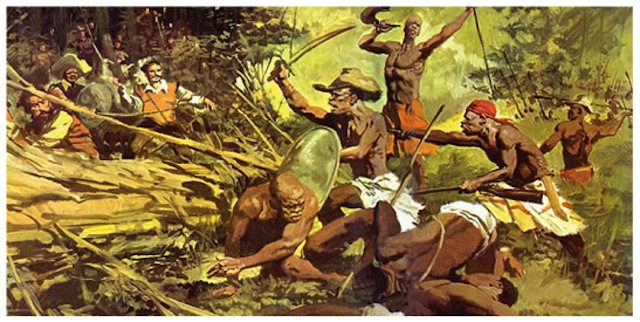

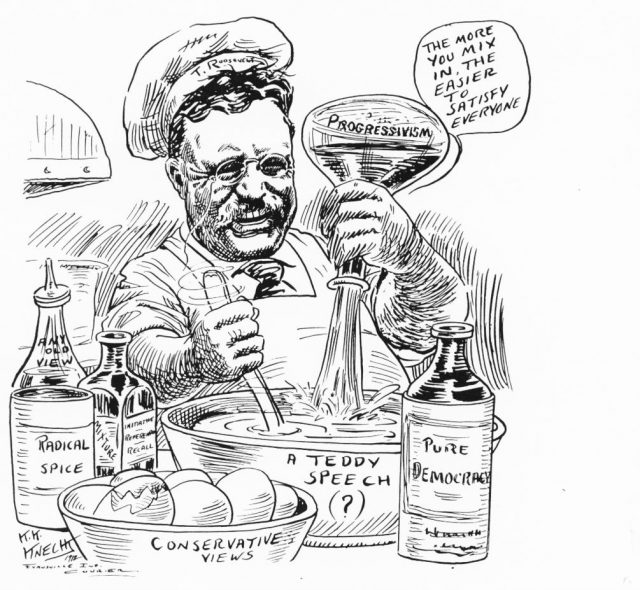

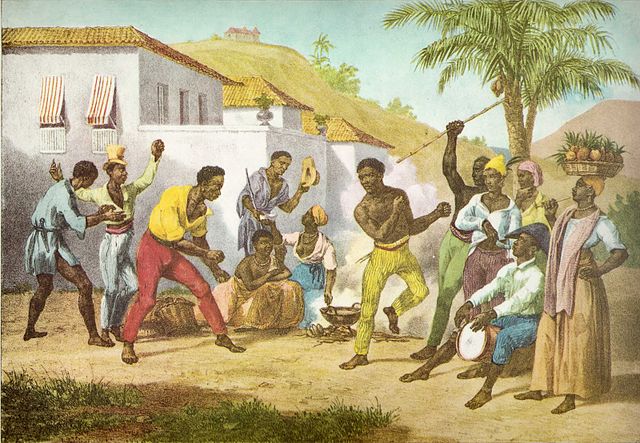

Capoeira or the Dance of War by Johann Moritz Rugendas (1825). The Brazilian dance of Capoeria is often associated with the Palmares quilombo. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Cheney’s new book claims many strengths but its effort to separate “myth” from “fact” represents its greatest achievement. Portuguese colonizers sought not only to destroy Palmares but also to expunge its existence from the historical record for fear that it would incite future slave rebellions. As a result, no artifactual evidence of the quilombo exists while surviving documentation reports precious little about Palmares, its people, and their points of view. Cheney nevertheless manages to shed light on Palmarians’ lived experiences by extrapolating meaning from among the colonizers’ exaggerations, inconsistencies, and omissions. By combining gripping narrative with first-rate scholarship, Cheney provides the most accessible and comprehensive study in English about “the most important historical event ever ignored by the world outside of Brazil.”

Glenn Alan Cheney, Quilombo dos Palmares: Brazil’s Lost Nation of Fugitive Slaves (New London Librarium, 2014)

You may also like:

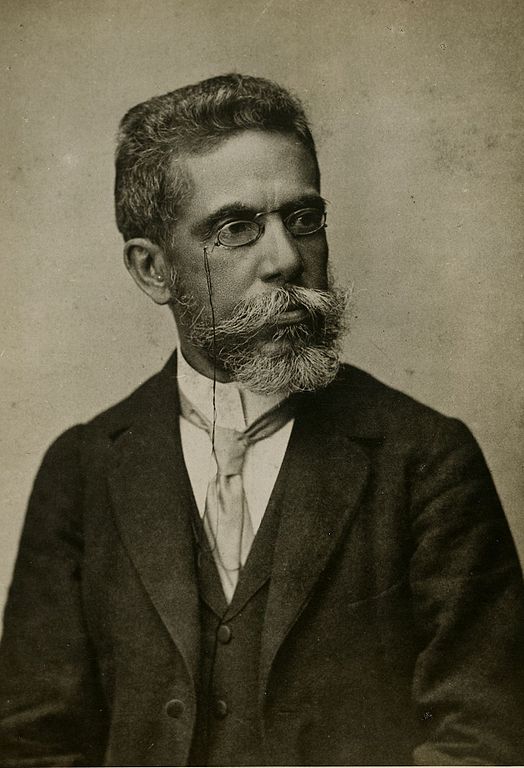

Eyal Weinberg on a new English translation of Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis’ short stories

Seth Garfield on his book In search of the Amazon: Brazil, the United States and the nature of a Region

Elizabeth O’Brien on labor history in the sugar industry in Brazil

Eyal Weinberg on labor history in Sao Paulo

Darcy Rendón on the social history of the lottery in Brazil