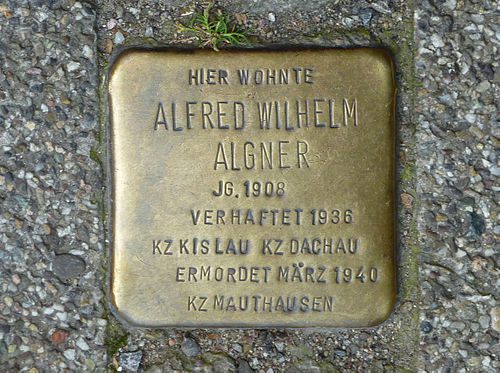

Just before dawn on July 16, 1942 the French Police began Opération Vent Printanier, or “Operation Spring Breeze.” That morning over 13,000 Jews were forcibly removed from their homes and trudged through the streets of Paris to the Vélodrome d’Hiver, the Winter Bicycle Racetrack, on the rue Nélaton in the city’s fifteenth arrondisement. Situated next to the Bir-Hakeim métro, not far from the Eiffel Tower, the Vel’ d’Hiv’ (as it was commonly called) was the first indoor track in France that hosted numerous sport and cultural shows. But in July 1942 the Vel’ d’Hiv’ hosted a much different spectacle: the inhumane detainment of Jews before their deportation to concentration camps in Parisian suburbs, such as Drancy and Beaune-la-Rolande, that sent Jews directly to Auschwitz. Inside of the Vel’ d’Hiv’ the French Police denied Jews water, food, medical attention, and even lavatories, treating the prisoners worse than livestock. Despite the atrocities that took place at the Vel’ d’Hiv’ and later in the concentration camps where families were separated and eventually convoyed to Auschwitz for extermination, the French rarely acknowledged or spoke about the Vel’ d’Hiv’. It was not until 1995 that the French Government, under the leadership of Jacques Chirac, addressed Vichy French compliance in the Vel’ d’Hiv’ roundup and the Nazis’ ultimate answer to the “Jewish Question.”

Philippe Pétain meeting Hitler in October 1940. (via Wikipedia)

Though a work of fiction, Tatiana de Rosnay’s poignant novel, Sarah’s Key, helps inform the reader about the lesser-known atrocities committed against French Jews under Nazi occupation and the Vichy government. Simultaneously set in July 1942 and sixty years later in July 2002, the novel alternates narratives between the lives of Sarah Starzynski, a ten-year old Jewish girl imprisoned with her parents in the Vel’ d’Hiv’, and Julia Jarmond, an ex-patriot American journalist writing a piece on the sixtieth anniversary of the Roundup. In researching her article, Julia begins to discover tragic secrets about Sarah’s life that have a devastating impact on Julia’s own life sixty years later.

Weaving together mystery, history, and intense emotion, de Rosnay provides an engrossing story. Though at times the plot can seem somewhat predictable this does not significantly undermine the book’s success. What is most significant and moving about the book is de Rosnay’s piercing criticism of France’s seeming ambivalence and long denial of involvement in the atrocities of the Holocaust including the Vel’ d’Hiv’ roundup. As one character poignantly remarks, “Nobody remembers the Vel’ d’Hiv’ children, you know… Why should they? Those were the darkest days of our country.” Despite the dedication of several sites in Paris to the memory of those deported during the war, such as the Mémorial de la Shoah and the Mémorial des Martyrs de la Déportation, there still remains a certain amount of unfamiliarity with Vichy France’s role in the Holocaust in France today. Sarah’s Key reminds readers that Vichy France’s compliance in the “Jewish Question” is not something to be forgotten or swept underneath the rug. It is a topic that deserves reexamination and further explanation.

Wikipedia on the round-up of French Jews

Mémorial de la Shoah website

A walking tour of the Mémorial des Martyrs de la Déportation with informative pictures

Trailer for the new film version of Sarah’s Key

Photo credits:

Jewish women in Paris, just before the roundup

Deutsches Bundesarchiv (German Federal Archive) via Wikimedia Commons

by

by

by

by

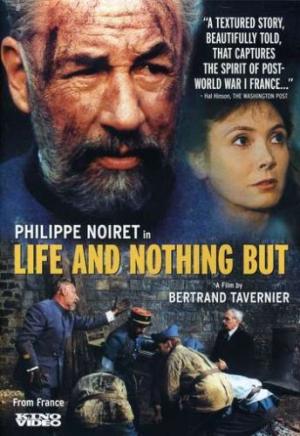

It’s no secret that the internet has made more images available to more people. Major libraries are digitalizing their visual collections and sites like Hulu and YouTube offer an enormous range of whole films and TV series. The quantity of visual resources is very exciting, and at the same time, daunting. Even if we only count collections of interest to historians, the sheer quantity of valuable images is increasingly hard to navigate. My goal is to point readers to interesting collections and websites (and books!) that might otherwise remain lost in the electronic thicket. And I invite readers to send in their own suggestions as well.

It’s no secret that the internet has made more images available to more people. Major libraries are digitalizing their visual collections and sites like Hulu and YouTube offer an enormous range of whole films and TV series. The quantity of visual resources is very exciting, and at the same time, daunting. Even if we only count collections of interest to historians, the sheer quantity of valuable images is increasingly hard to navigate. My goal is to point readers to interesting collections and websites (and books!) that might otherwise remain lost in the electronic thicket. And I invite readers to send in their own suggestions as well.