Kensey Wiggins

Anderson-Shiro Secondary School

Junior Division

Individual Exhibit

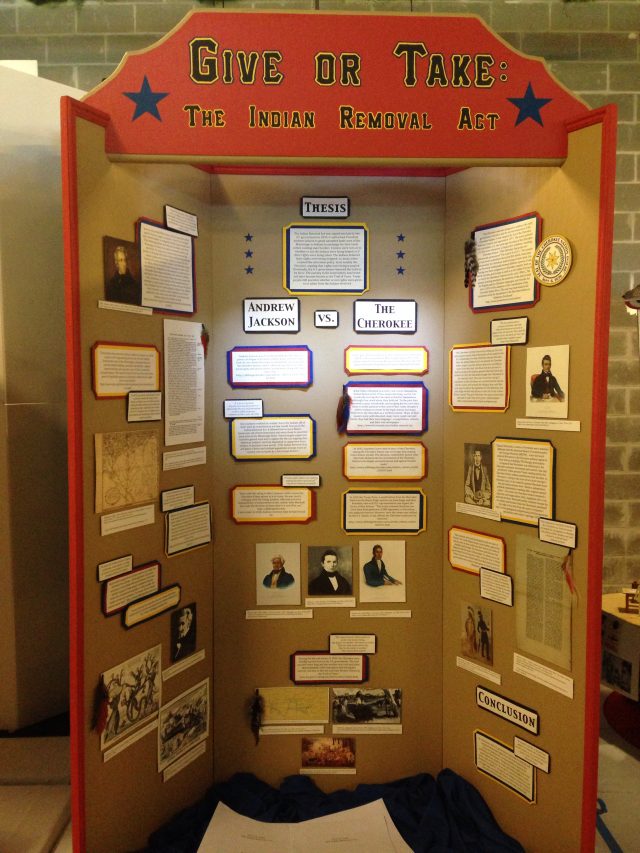

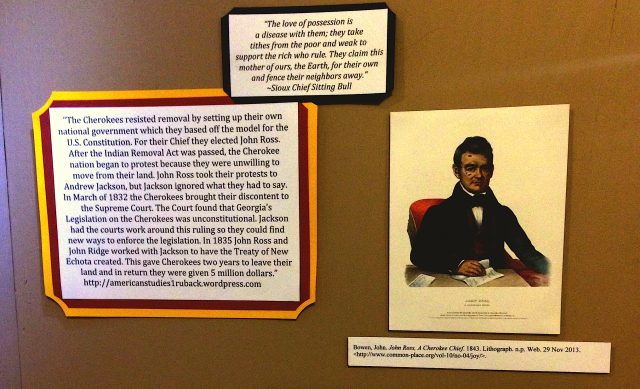

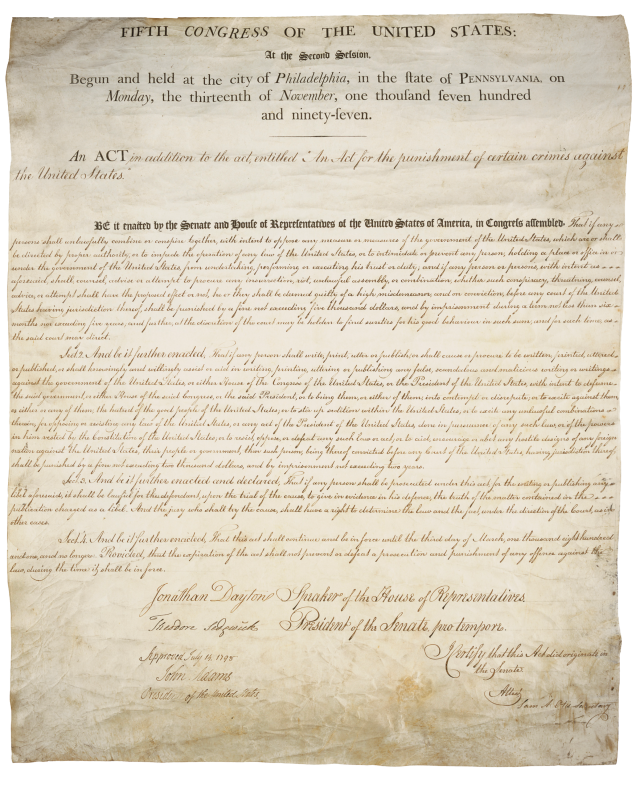

The Indian Removal Act was one of the most infamous moments in U.S. history. With the power of the federal government behind him, President Andrew Jackson authorized the removal of eastern Native American communities from their ancestral homelands and relocation to lands west of the Mississippi. Despite their best efforts, these Native tribes eventually lost sovereignty over their land and had to migrate west.

Kensey Wiggins’s Texas History Day exhibit explores the history behind this painful moment of Native American history. But he also sought to evaluate this controversial event from the perspective of Cherokee communities and President Andrew Jackson. Kensey talks about coming up with this topic in his process paper:

Ever since third grade, I’ve been leaming about American Indians. It was, and is, a common topic to cover in class. One thing the indians always seemed to be involved in was denied rights, whether it was land rights, rights to live, or individual rights. Because of this, when I saw Andrew Jackson vs. The Cherokees among the sample topics, it was instantly at the top of my choices. I asked my teacher for more information about Andrew Jackson and The Cherokees and soon realized what a great project it would make for this year’s topic.

My project relates to the theme in many ways. It focuses on the opposing beliefs about the rights involved with the indian Removal Act. One side believes they are helping the Indians by removing them. They believed they were giving them the right to live how they wanted. While the other side, believed the government was stripping the Indians’ rights and forcing them eff of their homeland. There was, and still is, huge controversy over the Indian Removal Act and whether or not the indians were given rights or if they were having their rights taken away.

This week’s Texas History Day projects:

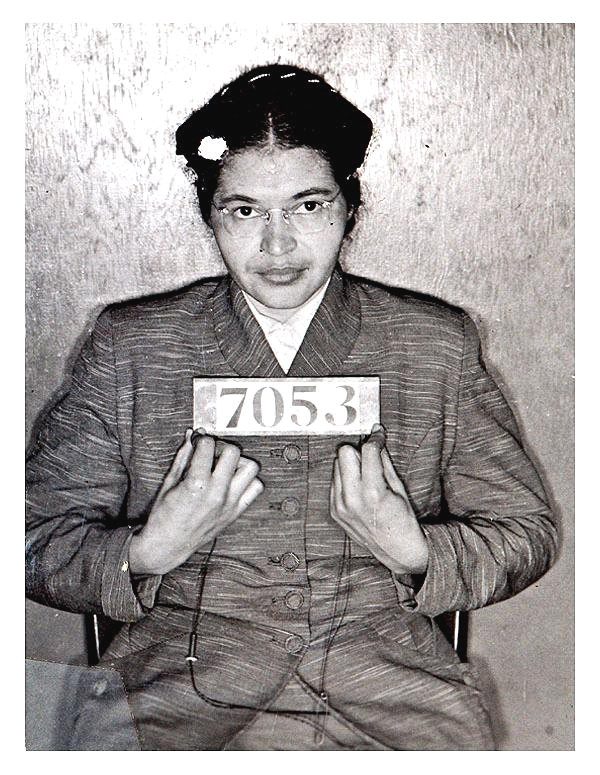

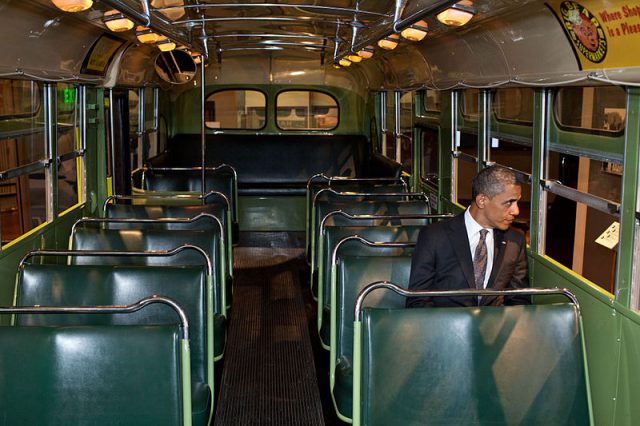

A website on an iconic Civil Rights moment

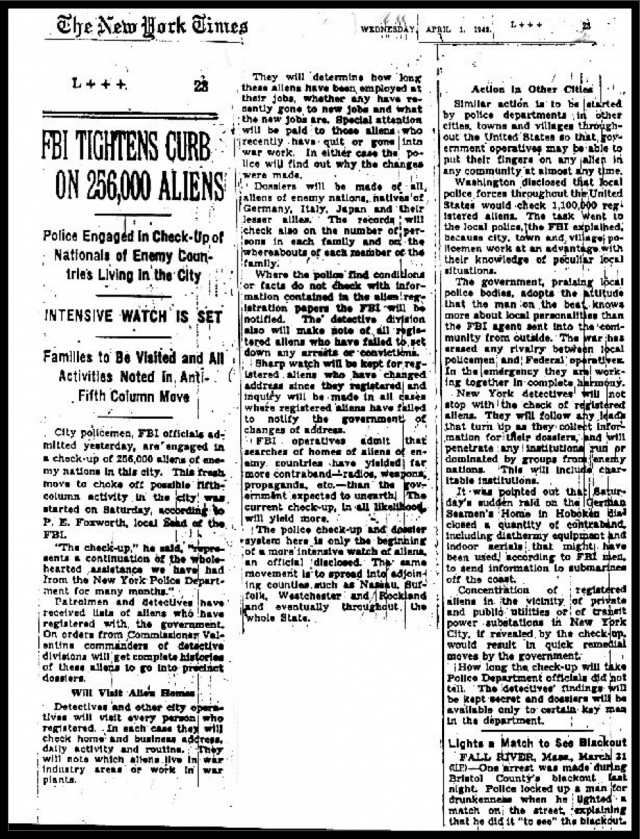

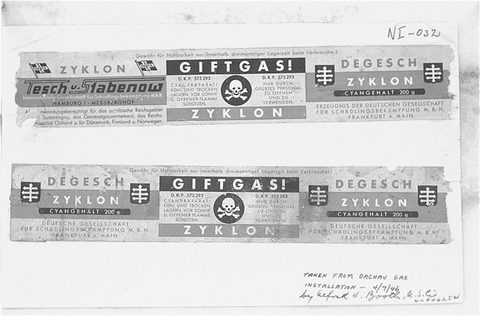

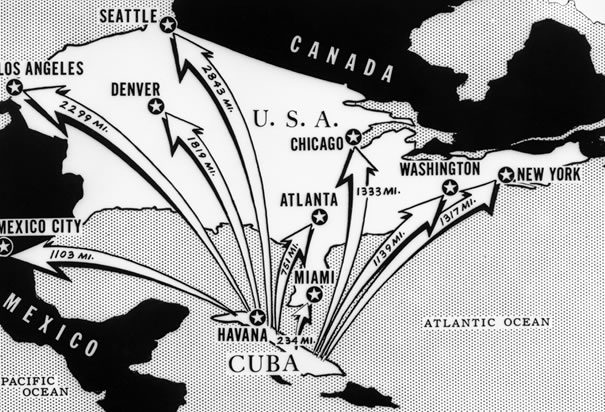

The often forgotten story of deportation and detention during WWII