By Charley S. Binkow

Images of war surround us today. We see high-definition photographs and videos of violence on our televisions, smartphones, and laptops almost constantly. But what was living through war like when people didn’t have instant videos or photographs? George Mason University’s Virginia Civil War Archive gives us a glimpse into the American media’s portrayal of the war at a time when ink-prints dominated the newspapers.

During the Civil War, Harper’s Weekly was one of the authoritative voices in news, both in the North and the South. What set them apart from their competition? Their prints brought the war to the people and illuminated a world far removed from our own. You can see Fredricksburg, Virginia before it saw battle, a map of the Battle of Bull’s Run, and a portrayal of rebels firing into a train near Tunstall’s Station.

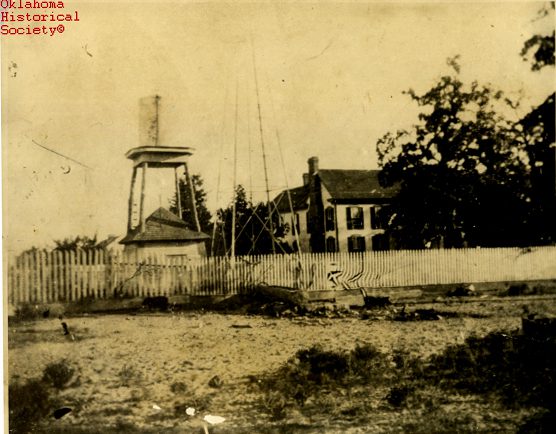

A Band of Rebels Firing Into the Cars Near Tunstall’s Station, Virginia, June 13, 1862 (George Mason University Libraries)

The collection is quite well organized. You can browse by titles, subjects, people, and more. A Civil War historian trying to find primary visual documents concerning Richmond during wartime can do so with a click of a button. An art historian can explore the different landscapes and figures expertly drawn by Harper’s staff—some of America’s best illustrators of the time worked for Harper’s. Almost anyone can find something interesting in this collection.

My personal favorite pieces are those that depict war scenes and their aftermath, like this dynamic, busy drawing of Colonel Hunter’s attack at the Battle of Bull Run or this poignant one of soldiers carrying away the wounded after battle. A lot of people relied on Harper’s Weekly and other newspapers to give them information about the Civil War. Seeing what these artists chose to portray, what they chose to omit, and how they created their scenes is fascinating.

This collection is one of many quality archives in the George Mason database. Eager history enthusiasts should take advantage of these primary documents. They’re informative, detailed, and just downright interesting.

More discoveries in the New Archive:

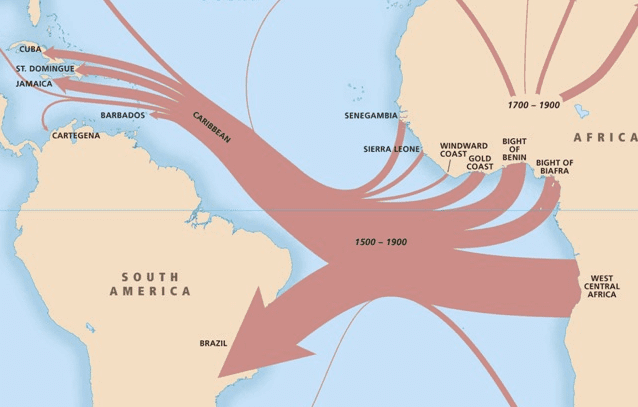

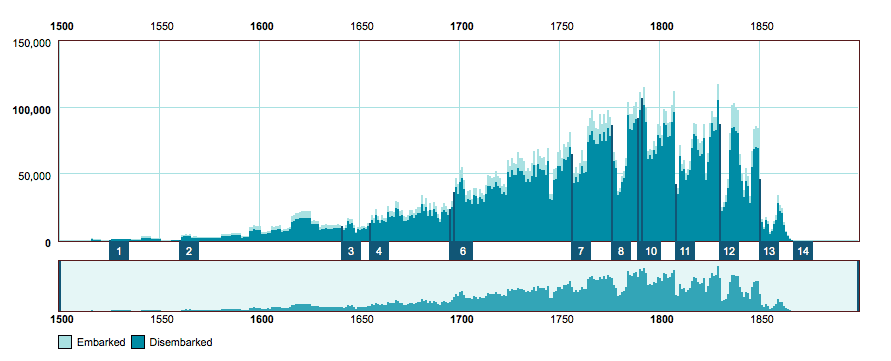

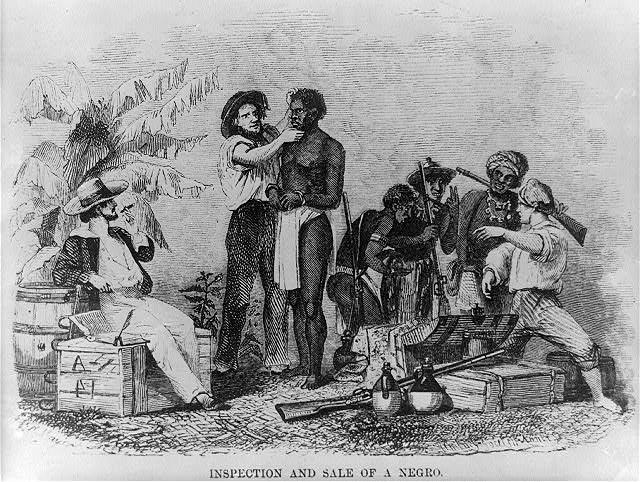

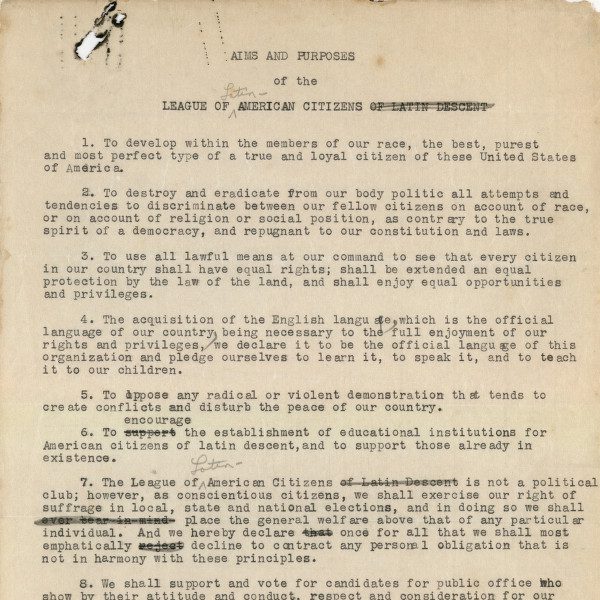

A website that charts the demographic, geographic and environmental history of the slave trade

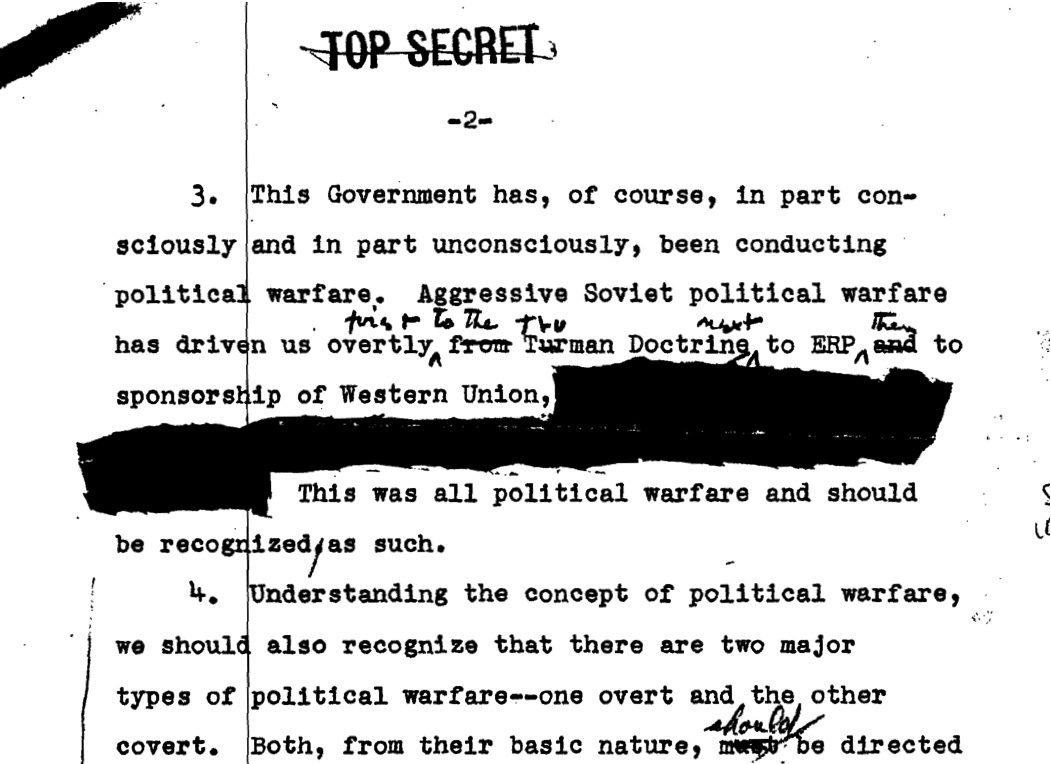

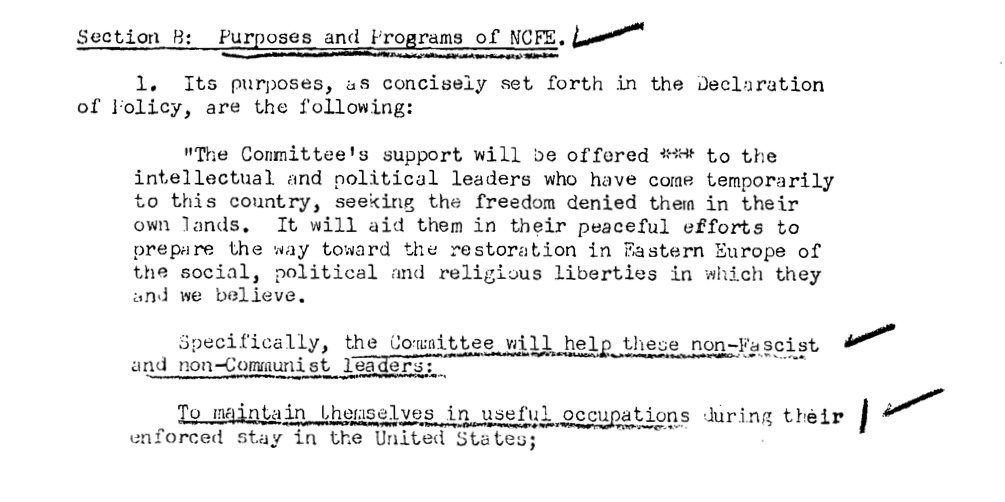

And newly declassified government documents that tell the story of Radio Free Europe