During the summer of 2016, we will be bringing together our previously published articles, book reviews, and podcasts on key themes and periods in the history of the USA. Each grouping is designed to correspond to the core areas of the US History Survey Courses taken by undergraduate students at the University of Texas at Austin.

On November 12, 2015, Not Even Past and the the Institute for Historical Studies at UT Austin sponsored a roundtable to discuss the Lessons and Legacies of the War in Vietnam. During that month, Not Even Past published a series of articles to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War.

We start with Mark A. Lawrence’s feature article: The War in Vietnam Revisited.

Next, Nancy Bui, the founder and President of the Vietnamese American Heritage Foundation considers the Vietnam War from a Vietnamese American Perspective.

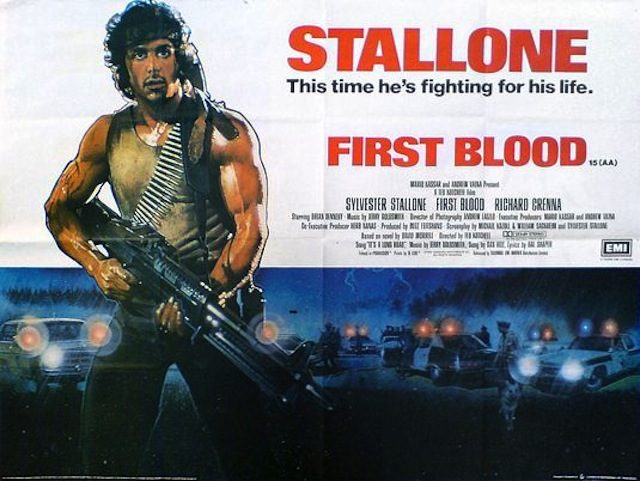

And Janet Davis shares a short meditation on cultural memory and the Vietnam War in two popular films: First Blood and Jaws

Over the years, Not Even Past has published a number of articles on the War in Vietnam by Mark Atwood Lawrence. This rich body of material covers wide range of topics and case studies giving our readers a chance to consider the War from a number of different angles:

LBJ and Vietnam: A Conversation

The Prisoner of Events in Vietnam

Changing Course in Vietnam — or Not

The Lessons of History? Debating the Vietnam and Iraq Wars

Others have considered the War in Vietnam in relation to broader topics:

Peniel Joseph explains how Muhammad Ali helped make black power into a global brand

Deirdre Smith shares some research on Vietnam between the United States and Yugoslavia.

And, Michael J. Kramer discusses on representing LBJ and power through the medium of dance in The Seldoms Bring LBJ and the 1960s Into the Present in Their Investigation of How Power Goes.

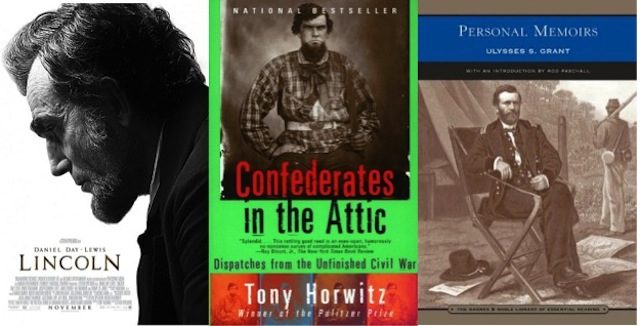

Recommended Reading:

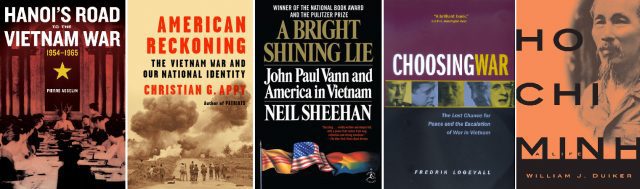

Mark A. Lawrence shares a list of Must Read Books on the Vietnam War

Jack Loveridge recommends Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72, by Hunter S. Thompson (1972)

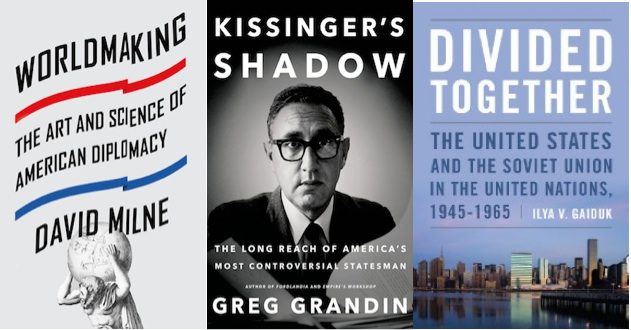

Clay Katsky suggests Kissinger’s Shadow, by Greg Grandin (Metropolitan Books, 2015)

And finally, Mark A. Lawrence shares a list of books on International History and the Global United States including his edited collection The Vietnam War: An International History in Documents (Oxford University Press, 2014).

15 Minute History:

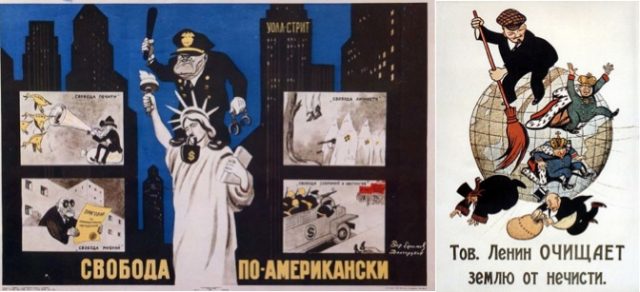

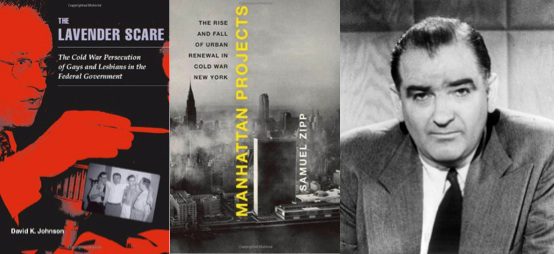

America and the Beginnings of the Cold War

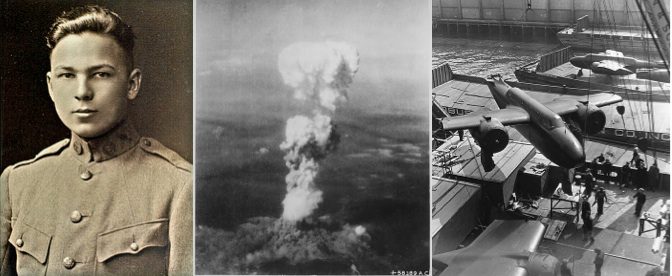

The Cold War dominated international politics for four and a half decades from 1945-1989, and was defined by a rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union that threatened—literally—to destroy the world. How did two nations that had been allies during World War II turn on each other so completely? And how did the United States, which had been only a marginal player in world politics before the war, come to view itself as a superpower?

In this episode, historian Jeremi Suri discusses the beginnings of the Cold War (1945-1989) its origins in the “unfinished business” of World War II, the role of the development of atomic weapons and espionage, and the ways that it changed the United States in just five short years between 1945 and 1950.

The US and Decolonization after World War II

Following World War II, a large part of the world was in the hands of European powers, established as colonies in the previous centuries. As one of the nations that came out on top of the geo-political situation, the United States was looked to with hope by aspiring nationalist movements, but also seen as a potential source by European allies in the war as a potential supporter of the move to restore the tarnished empires to their former glory. What’s a newly emerged world power to do?

Guest R. Joseph Parrott takes a look at the indecisive position the United States took on decolonization after helping liberate Europe from the threat of enslavement to fascism.