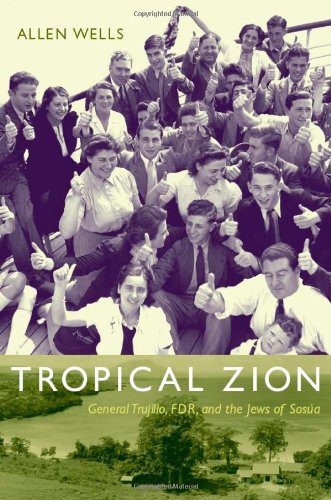

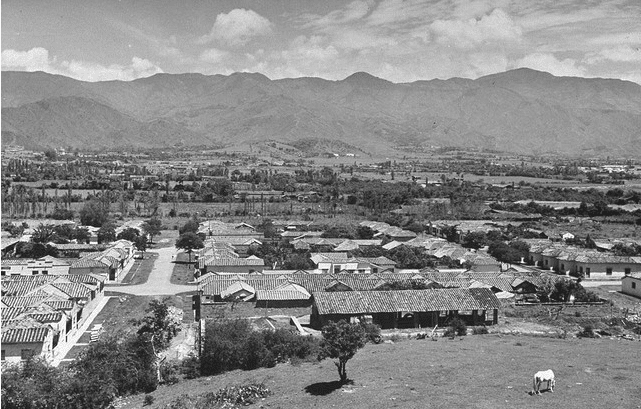

In October 1937, Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo ordered his troops to slaughter Haitians living in the Dominican frontier and the Cibao. The horrific violence left as many as 15,000 dead. Trujillo apologists managed to justify the action nationally, but the massacre created an international public relations nightmare for the regime. Newspapers cited Trujillo’s ruthlessness and compared him to Hitler and Mussolini. Trujillo quickly moved to restore his credentials as an anti-fascist ally of the United States by offering refuge to 100,000 European Jews fleeing Nazi Germany. In Tropical Zion, Allen Wells tells the story of the establishment and decline of the small Jewish agricultural colony at Sosúa in the Dominican Republic and illustrates the significance of the colony in the international sphere. While only a handful of Jews migrated to the Dominican Republic during the Holocaust, Wells argues that ultimately, Sosúa saved lives and that its history uncovers the complex intersection of Zionism, U.S.-Dominican relations, American and Europe anti-Semitism, and the racism of the Trujillo regime.

The horrific violence left as many as 15,000 dead. Trujillo apologists managed to justify the action nationally, but the massacre created an international public relations nightmare for the regime. Newspapers cited Trujillo’s ruthlessness and compared him to Hitler and Mussolini. Trujillo quickly moved to restore his credentials as an anti-fascist ally of the United States by offering refuge to 100,000 European Jews fleeing Nazi Germany. In Tropical Zion, Allen Wells tells the story of the establishment and decline of the small Jewish agricultural colony at Sosúa in the Dominican Republic and illustrates the significance of the colony in the international sphere. While only a handful of Jews migrated to the Dominican Republic during the Holocaust, Wells argues that ultimately, Sosúa saved lives and that its history uncovers the complex intersection of Zionism, U.S.-Dominican relations, American and Europe anti-Semitism, and the racism of the Trujillo regime.

In 1938, following the violent attacks on Jews throughout Germany and parts of Austria that came to be known as Kristallnacht, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt organized a conference at Évian-les-Bains, France in hopes of developing a strategy to handle the massive Jewish flight from Germany and Austria. However, American and European anti-Semitism prevented the United States, England, France, and many other countries from offering Jews a place of refuge. Moreover, they refused to consider Palestine as a resettlement site. At Évian, Trujillo’s brother Virgilio, stepped into the gap and offered Jewish refugees a safe haven in the Dominican Republic. Wells emphasizes that although Trujillo sought to use the offer to repair his image after the massacre and as a means of whitening the Dominican population, he remained the only one to volunteer his country for Jewish resettlement. Conference participants considered and rejected a variety of locations, including Angola and British Guiana, but in the end the Dominican Republic emerged as the only settlement site. Wells details the immigrant selection process, the immigrants’ movement from countries of transit to the Dominican Republic, and the complicated process of community formation after their arrival. While the settlement faced several difficulties from the outset, the biggest source of contention remained the nature of the colony – would it be a temporary place to await the end of the war or a true farming community? Although Jewish-American philanthropists, the Dominican Republic Settlement Association (DORSA), and Trujillo imagined the colony as an agricultural settlement, DORSA approved the migration of settlers and non-settlers alike. Non-settlers expressed little interest in farming, preferring a town existence dependent on DORSA stipends that diverted the colony’s funds from its growing dairy industry. This became a major source of tension between settlers and non-settlers. As the war came to an end, non-settlers, derisively referred to as “America-Leavers,” quickly moved to secure U.S. visas and leave the Dominican Republic. This initiated the colony’s decline, which worsened as dairy farmers also left the island for the United States in order to provide a better future for their children.

Wells demonstrates that Trujillo used the practice of gift-giving and highly ritualized public ceremonies to create circuits of exchange between himself, the Roosevelt administration, DORSA, and the colony at Sosúa. First, Trujillo’s Évian offer presented a solution for President Roosevelt who faced critiques from powerful Jewish-Americans regarding the U.S.’s strict immigration policies and the rising tide of U.S. anti-Semitism. Second, Trujillo, who owned the prospective Sosúa settlement site, generously donated the property to the colony in a symbolic act of friendship that would cement patron-client ties between himself, DORSA, and the Jewish settlers. The regime then hosted a large public ceremony to celebrate the signing of a contract between the Dominican government and DORSA that guaranteed settlers religious freedom and civil and legal rights. Wells argues that as clients of Trujillo, DORSA and Jewish settlers were expected to support the regime by lobbying the Roosevelt administration on Trujillo’s behalf, participating in state rituals, and refraining from criticism. These actions helped confer legitimacy on the dictatorship and minimize Trujillo’s reputation for brutality. Moreover, he suggests that Trujillo’s offer and the lobbying of DORSA officials helped create an environment conducive to the renegotiation of the U.S. receivership of Dominican customs and allowed Trujillo to re-establish Dominican financial independence. The successful re-institution of Dominican control over its customs receipts remains one of the hallmarks of the Trujillo regime.

The son of Sosúa settler Heinrich Wasservogel, Wells has intimate knowledge of life in the small tropical sanctuary. His masterful narrative is a must read for those interested in the Jewish Diaspora, dictatorship in Latin America and the Caribbean, and U.S.-Dominican relations during the Trujillo era.

Photo credits:

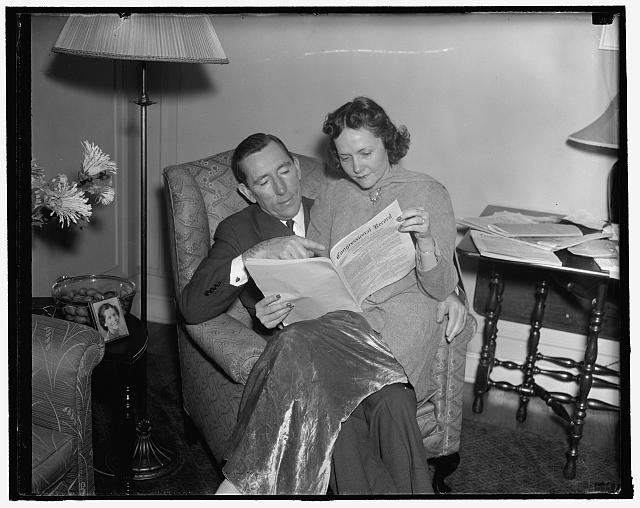

Harris & Ewing, “Gen. Trujillo given luncheon at Capitol. Visiting Washington on a goodwill tour is former Dominican Republic President Gen. Rafael Trujillo. The general was accorded a luncheon today at the Capitol by Sen. Theodore Green Rhode Island. Avidly talking to the General, who speaks no English, are Senators Green and Guy Gillette while Minister Andres[?] Pastoriza rapidly interprets. Left to right: Trujillo, Sen. Green, Pastoriza, Sen. Gillette,” Washington, DC, 7 July 1939.

Harris & Ewing via The Library of Congress

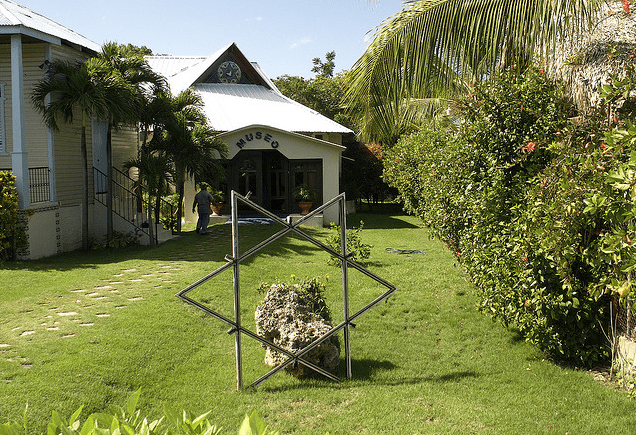

Colin Rose, “Jewish Museum in Sosua,” 24 December 2006

Author’s own via Flickr Creative Commons

Flickr user muckster, “Sosua Jewish Museum: Children of Immigrants,” 9 February 2007

Author’s own via Flickr Creative Commons

You may also like:

This interview, conducted in May 2011, with General Imbert, one of the men who assassinated Rafael Trujillo in 1961. (BBC News)

Adrian Masters’ review of The Doubtful Strait, Ernesto Cardenal’s poem chronicling the history of Nicaragua from colonial discovery to the Somoza dictatorship.

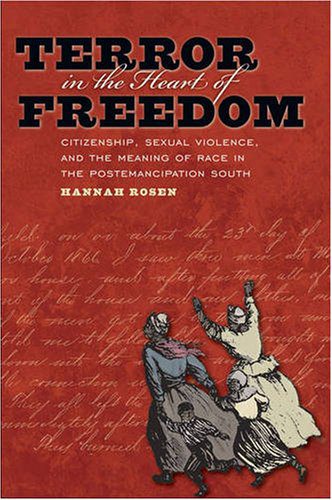

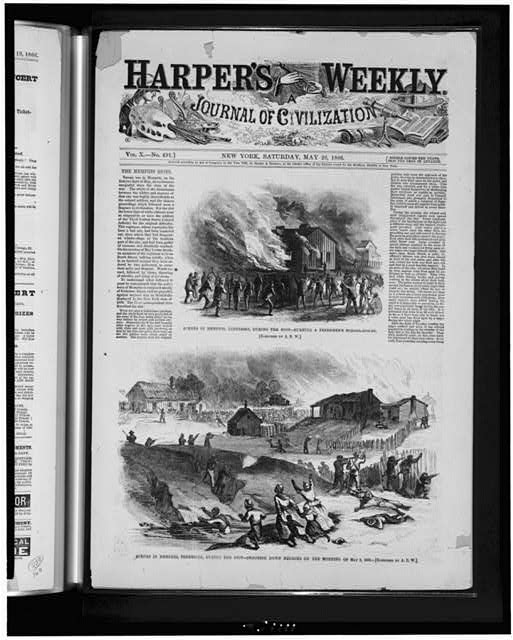

Hundreds of thousands died or were wounded in combat, entire cities were destroyed, and afterwards, the large segment of the nation that had seceded had to be reincorporated into the national body, and a new citizen-subject remained to be embraced by post-bellum societies. Hannah Rosen’s Terror in the Heart of Freedom analyzes the experiences of recently freed blacks, released from the bonds of slavery and plantation life, who sought to create new lives as freedmen and women. Many headed to cities as part of a “mass exodus from slavery.” The city of Memphis, Tennessee became one such “city of refuge” where freedpersons practiced their freshly conferred citizenship. They established new communities, built churches, opened their own schools, and formed African American benevolence societies that sponsored community events. In short, freedpersons in Reconstruction Memphis, as in many other cities, catalyzed changes in the socio-spatial boundaries of urban spaces that had previously been closed to them.

Hundreds of thousands died or were wounded in combat, entire cities were destroyed, and afterwards, the large segment of the nation that had seceded had to be reincorporated into the national body, and a new citizen-subject remained to be embraced by post-bellum societies. Hannah Rosen’s Terror in the Heart of Freedom analyzes the experiences of recently freed blacks, released from the bonds of slavery and plantation life, who sought to create new lives as freedmen and women. Many headed to cities as part of a “mass exodus from slavery.” The city of Memphis, Tennessee became one such “city of refuge” where freedpersons practiced their freshly conferred citizenship. They established new communities, built churches, opened their own schools, and formed African American benevolence societies that sponsored community events. In short, freedpersons in Reconstruction Memphis, as in many other cities, catalyzed changes in the socio-spatial boundaries of urban spaces that had previously been closed to them.

Subjugating and Christianizing these unincorporated indigenous peoples, called bárbaros (translated as “savages”) were major objectives of late eighteenth-century Bourbon reforms. David Weber concludes that “pragmatism and power usually prevailed over ideas,” with Bourbon policy usually favoring a realistic approach to dealing with these native groups, alternatively using armed conflict or negotiation when each seemed most useful. The Spanish crown was only one of several interest groups—including Bourbon officials, the military, and the colonial bureaucracy—competing for the loyalty of indigenous peoples. Indians from geographically disparate Spanish borderland regions had more in common socially and culturally with each other than with the inhabitants of nearby colonial centers, like Mexico City or Lima. Weber justifies the range of his study by contending that others have looked at Spanish and native relations only from a local perspective, failing to account for the diverse challenges these groups posed for Bourbon rulers.

Subjugating and Christianizing these unincorporated indigenous peoples, called bárbaros (translated as “savages”) were major objectives of late eighteenth-century Bourbon reforms. David Weber concludes that “pragmatism and power usually prevailed over ideas,” with Bourbon policy usually favoring a realistic approach to dealing with these native groups, alternatively using armed conflict or negotiation when each seemed most useful. The Spanish crown was only one of several interest groups—including Bourbon officials, the military, and the colonial bureaucracy—competing for the loyalty of indigenous peoples. Indians from geographically disparate Spanish borderland regions had more in common socially and culturally with each other than with the inhabitants of nearby colonial centers, like Mexico City or Lima. Weber justifies the range of his study by contending that others have looked at Spanish and native relations only from a local perspective, failing to account for the diverse challenges these groups posed for Bourbon rulers. Weber analyzes these Indian societies based on how they defended their independence, rather than grouping them by geography. Yet, on the imperial periphery, cooperation and integration often came before conflict. Weber contends that the incompatibility between Spaniard and native was not as pronounced as other scholars have claimed. One successful tactic the Bourbons used to integrate native populations without open conflict was by taking over the independent missionaries, especially Jesuits, that operated in many peripheral areas. The book concludes by tracing the story of the indios bárbaros into the national period, a time in which the leaders of the new republics abandoned old Bourbon policies of negotiation. They came to regard independent natives as inferior peoples, and, in Argentina, the most radical case, actively exterminated the indigenous population.

Weber analyzes these Indian societies based on how they defended their independence, rather than grouping them by geography. Yet, on the imperial periphery, cooperation and integration often came before conflict. Weber contends that the incompatibility between Spaniard and native was not as pronounced as other scholars have claimed. One successful tactic the Bourbons used to integrate native populations without open conflict was by taking over the independent missionaries, especially Jesuits, that operated in many peripheral areas. The book concludes by tracing the story of the indios bárbaros into the national period, a time in which the leaders of the new republics abandoned old Bourbon policies of negotiation. They came to regard independent natives as inferior peoples, and, in Argentina, the most radical case, actively exterminated the indigenous population.

The “Articles for Immoral Use” were devices and potions for contraception or abortion. Commonly called the

The “Articles for Immoral Use” were devices and potions for contraception or abortion. Commonly called the

It places gender in the context of the roles of the church and the paternalistic factory owners as well as the memories of the workers, to tell this history of forgotten myths and morals in the workplace. Dulcinea in the Factory shows that male factory owners, managers, and church officials saw themselves as

It places gender in the context of the roles of the church and the paternalistic factory owners as well as the memories of the workers, to tell this history of forgotten myths and morals in the workplace. Dulcinea in the Factory shows that male factory owners, managers, and church officials saw themselves as

S. Hutchinson, 1793 © National Maritime Museum Collections

S. Hutchinson, 1793 © National Maritime Museum Collections