by Danielle Maldonado

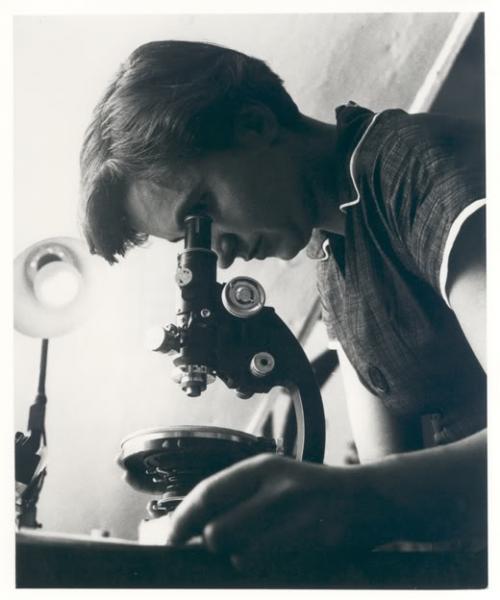

Rosalind Franklin (1920-1958) was an English biophysicist who made critical scientific contributions to our knowledge of DNA. Her data enabled crucial breakthroughs in the field of biochemistry, notably the discovery of DNA’s double helix structure. For Texas History Day, Danielle Maldonado produced a video performance of Franklin’s life and work, outlining her achievements and explaining what life would have been like for the iconic scientist. You can watch her dramatic and historical performance here. Danielle argues that Fanklin’s work represented a major turning point in history:

“Everyone knows who Dr. James Watson, Francis Crick, and Maurice Wilkins are. If you don’t, they are credited with the discovery of the structure of DNA. They won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962. Without the help of Rosalind Franklin, this great turning pointing in history wouldn’t have been possible. The base of genetic biochemistry was stabilized by Rosalind Franklin’s contributions to the discovery of the structure of DNA….This knowledge has helped scientists discover other biological breakthroughs that would’ve otherwise been impossible. Told from the viewpoint of Rosalind Franklin, she expresses the struggles of completing all the main research on her own and explains how many genetic advancements have been made since then. Rosalind Franklin’s work helped pave a new road for biochemistry to travel.”

“The base of genetic biochemistry was stabilized by Rosalind Franklin’s contributions to the discovery of the structure of DNA. This is a turning point in history, and is thus significant in history, because there is so little that we understand about human life. In the 21st century, being able to recognize and treat genetically inherited diseases and disorders impacts our lives greatly. The structure of DNA is one more puzzle we were able to solve, though not all puzzles are solvable. We may never be able to see the whole picture that lies at the end, but we will continue to piece it together, one strand of DNA at a time.”

Danielle Maldonado

Division II

Individual Performance

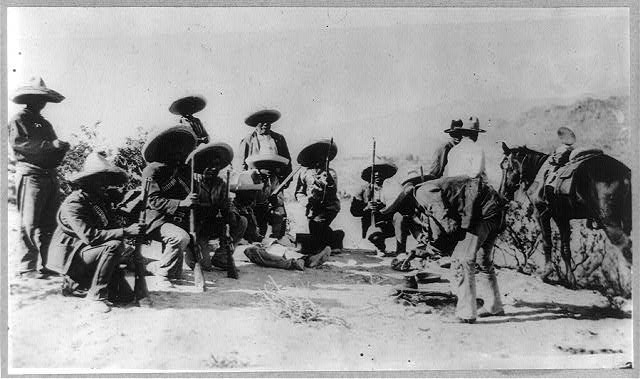

Photo Credits:

Rosalind Franklin performing an experiment (Image courtesy of Science Blogs)

Images used under Fair Use Guidelines