Even the most gifted teachers had to learn how to teach history and most of us needed a lot of help getting started. This month Not Even Past asked graduate students to reflect on their first teaching experiences as Teaching Assistants in History classes. They responded with insight, humor, and even a little hard won wisdom. Reflections here by Chloe Ireton, Cacee Hoyer, Jack Loveridge, Cameron McCoy, and Elizabeth O’Brien.

Chloe Ireton

As a graduate student in the History Department at the University of Texas at Austin, I have had valuable opportunities to learn how to teach history. Over the last three semesters I have worked as a Teaching Assistant in a lecture course on United States History since 1865. The 300+ students in the course listen to two hours of lecture a week and then participate in discussion sections of thirty-five students for one hour a week, taught by one of four TAs or Dr. Megan Seaholm who directs the course. The sections aim to create small learning environments for students to engage in sustained discussion and focus on important academic skills such as critical thinking, reading, writing, and discussion skills. Each seminar leader also creates a closed online social media group where students complete tasks, engage in graded online discussions about specific topics, and communicate with other students and the Teaching Assistant about the course.

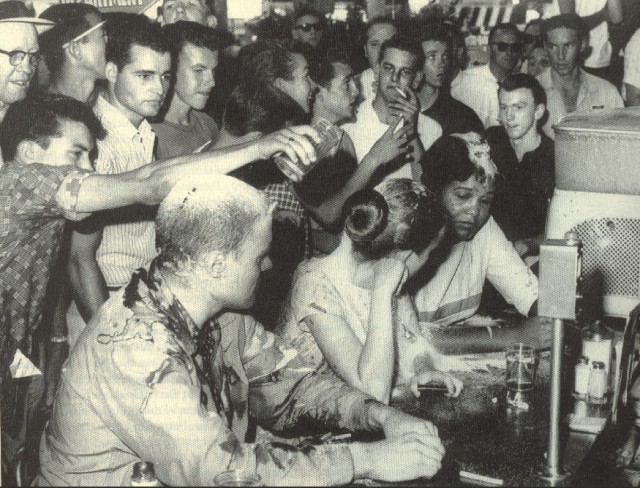

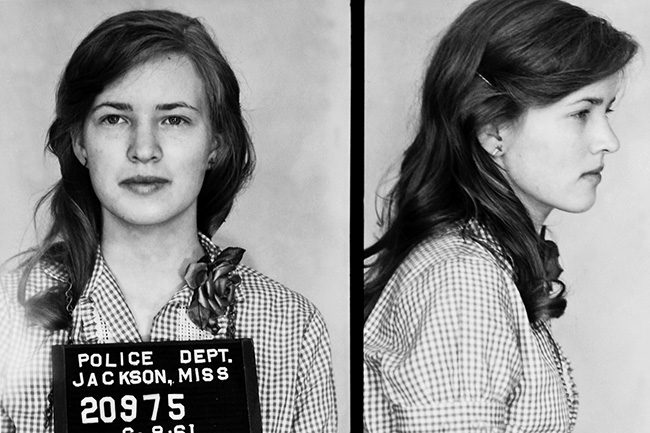

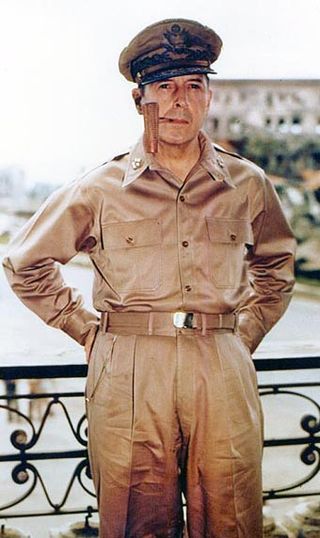

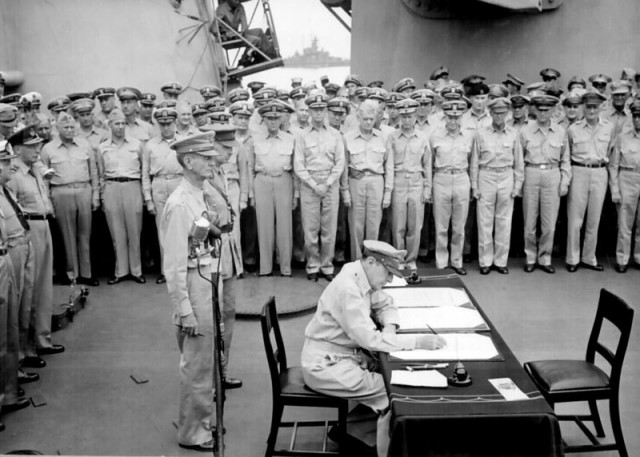

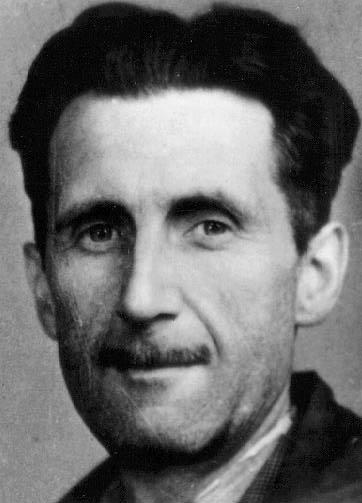

This US History course is the first large lecture courses in the History Department to carry an “Ethics and Leadership Flag.” All UT undergraduates are required to take at least one Ethics Flag course, which is intended to “expose students to ethical issues and to the process of applying ethical reasoning in real-life situations.” The Ethics Flag component of the course taught students to explore the ethical reasoning of historical actors and to interrogate contrasting moral values in different historical time periods. We focused on four key ethical themes: poverty in the late nineteenth century, eugenics and state-sanctioned forced sterilizations in the early twentieth century, the Targeting of Civilians during the Second World War and specifically the use of atomic bombing, and lastly Civil Disobedience in the second half of the twentieth century. In the seminars, students reflected on the ethical reasoning of historical actors through primary source analysis. What did each person see as the key ethical issue at stake? Who did they see as the key moral actor(s) responsible for solving this issue? Did they see any alternatives? Did they see a certain action as ethically required or permissible and why?

At the end of the course, feedback from many students referred to these discussions as hugely important in the development of their critical thinking skills and their understanding of others and of history in general. The majority of the students found it enlightening to engage in discussions with peers who approached the topics differently from themselves. As the discussion leader, I found that the ethical framework of these seminars encouraged a high level of student engagement and provided a space for students to learn important skills in primary source reading, critical thinking, argumentation, and discussion, but most importantly in developing a sense of historical differences. I was fortunate to collaborate in the process of planning and integrating of the Ethics and Leadership Flag into the course. The TAs, Dr. Megan Seaholm (History), Dr. Eric Busch (Sanger Learning Center), and Dr. Jess Miner (Center for the Core Curriculum) met every fortnight during three academic semesters to plan seminars and debate the most appropriate forms of assessment. In our fortnightly meetings, we took turns presenting seminar lesson plans, each of which we critiqued until deciding on the most appropriate format. This experience provided a crucial venue for professional development in discussing best teaching practices with experienced teachers.

In organizing discussion seminars for this course, I adhered to a pedagogical philosophy called “task-based learning.” It is broadly defined as student centered and often student led learning through students’ active engagement in relevant tasks, commonly in collaboration with their peers. Adherents of this pedagogy believe that when learners are actively engaged in a task they become invested in the outcome of their own learning and the skills that they acquire along the way. In task-based learning approaches, the educator acts as a guiding toolbox to aide students’ learning rather than as a vessel that carries knowledge and imparts it in a teacher centered learning environment. For one weekly seminar, I planned a task-based lesson on National Security and free speech in the United States during World War I, which aimed to elaborate on the theme of the lecture that week, develop students’ primary source reading and critical thinking skills, and abilities to analyze historical sources and themes. Students read The Espionage Act of 1917 and President Woodrow Wilson’s 1917 speech about the need to enter WWI in order to make a world “safe for democracy.” I provided guiding questions and divided students into small discussion groups, which identified a wide array of perspectives on what these sources signified and whether they could and should be read together. In these discussions, students engaged actively in the type of historical thinking skills that we wanted them to acquire. For example, since the class represented a variety of opinions about the significance of the readings when read together, students became aware of the importance of historiographical debate and the role of historians’ perceptions in their own interpretations. In the second half of the class, students read two court cases where individuals who publically spoke out against the draft during WWI were found guilty of charges under the Espionage Act. For example, students read excerpts from Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 47 (1919), a United States Supreme Court decision, in which Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., concluded that those distributing leaflets that urged resistance to the draft could be convicted of an attempt to obstruct the draft (a criminal offense) because they posed a “clear and present danger.” This activity helped to contextualize the meaning and effect of the Espionage Act and prompted students to revisit the original question of whether we should read President Woodrow Wilson’s speech on the need to spread democracy across the world alongside the Espionage Act. For the post-seminar online discussion task, students reflected on the questions and documents that they found most interesting. They also read a news article about the Obama Administration’s use of the Espionage Act in order to engage in a discussion on the differences between the use and purpose of the Espionage Act in the early twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

This semester I am embarking on a new challenge as I am working as a Supplemental Instructor for a large US History Survey course. This means that I am offering two hourly discussion sections every week for students in this course. These seminars are designed to help students with course material and also to develop the skills that they need to become successful and autonomous learners. We will be covering diverse topics such as reading and note-taking skills, writing skills, preparation for specific assignments, discussion seminars, debating skills, historical thinking skills, and reading and analyzing primary sources, to name just a few. All of these sessions aim to support students’ progress in the class. The challenging aspect of these seminars is that they are voluntary. As the discussion leader, I have to be prepared for attendance to vary between a handful of students and hundreds. The Supplemental Instruction program (directed by the Sanger Learning Center) also provides continuing professional and pedagogical support through biweekly meetings with a supervisor and Supplemental Instructors from other departments within the College of Liberal Arts. These meetings aim to provide a forum to discuss teaching methods and our classroom experiences over the course of the semester.

Completing my PhD at the History Department at the University of Texas at Austin has provided an unrivalled venue for developing as a historian. Excellent support of my intellectual trajectory and research project (which I have not discussed in this post), combined with the opportunity to teach on exciting and innovative History courses make this a wonderful department in which to train as a historian.

***

Cameron D. McCoy

I would like to start this reflection with a quote from a friend. When asked to describe his undergraduate experience at the United States Naval Academy, he replied, “It was everything I thought it would be and a thousands things I never imagined.” As a UT History Teaching Assistant for the course in the Black Power Movement, my friend’s words found a suitable place to rest.

I am sure TAs do not even cross the mental radar of students until after the first exam. We morph into something a little more than a disembodied e-mail solicitor by the midterm, and then two weeks before the final the TA becomes the end-all-be-all. Prior to this—according to most students—the teaching assistant is the class scribe, sends pestering e-mails, listens and deals with complaints, and is supposed to know the syllabus verbatim at a moment’s notice. Of course this all falls under “… and a thousand things I never imagined.” Anything unfavorable is the Teaching Assistant’s fault and anything favorable is the professor’s doing. I can always count on the behavior of the students to hit the same currents throughout each semester, which brings the comfort of knowing it is “everything I thought it would be” and the familiar chaos of “a thousand things I never imagined.”

Surprisingly, I discovered that I never had to sell history to the students. Neither was I under fire in attempting to defend the discipline and virtues of history. The professor designed the course in such a way that the material was palatable and fairly easy to consume.

I did find when grading exams that the students’ interpretation of the material varied. Each student personalized the material, from ultra-conservative to highly polemic, from rigid to liberal, and from nonchalant to finely precise. I found this fascinating and the variety assisted me in better understanding how students communicated. I also enjoyed reading essays that expressed the student’s growth from learning the course material. Several students’ views drastically changed throughout the semester, specifically concerning how the black power movement connected directly to how universities function and how many social issues of 2014 are direct descendants of the 1960s.

***

Jack Loveridge

Teaching History at a major public university in the United States means stretching outside of your intellectual comfort zone on a regular basis. Teaching Assistants (TAs) are often assigned to courses somewhat beyond their principal fields of study. Many unwitting Latin Americanists, for instance, might find themselves cast before a crowd of inquisitive undergraduates, struggling to cough up the basics of the Missouri Compromise. A historian of Russia might be cornered in a hallway and asked where everyone was running during the Runaway Scrape or what was so abominable about the Tariff of Abominations. These are our occupational hazards.

As a student of British imperial rule in South Asia in the twentieth century, I felt a nervous pang when I found myself TA-ing for Dr. James Vaughn’s course, entitled History of Britain: The Restoration to 1783. Though a bit closer to home for me than the assignments drawn by many of my colleagues, the long, gouty march of Stuarts and Hanoverians, punctuated by a decade of Cromwellian fun, is hardly my strong suit. Not only did the scope of the course predate my period of expertise, part of it also predated Britain itself. (England and Scotland did not tie the knot until the Act of Union in 1707. Incidentally, whether their marriage will endure the test of time shall be seen with a Scottish independence referendum this September.) Beyond that bit of Jeopardy trivia, what on earth did I know about the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries?

My initial hesitation notwithstanding, I plunged forth into my first teaching assignment. I read the requisite materials and then some, devoured half a dozen BBC documentaries, and memorized the English monarchs since William the Conqueror for an added parlor trick. As it turned out, this period of English history helped to explain a great deal about the evolving British Empire and, more surprisingly, the contemporary global economy. Most of all, engaging with an unfamiliar period of history proved humbling, but it also gave me an opportunity to approach the readings and lectures as a student and not a teacher. This, in turn, ultimately helped me to address students’ questions with a bit more empathy.

On occasion, one of my many bright students would ask a question for which I simply had no good answer. At first, these instances embarrassed me. How could I, the respected TA, wearer of fishbone-patterned blazers, and sipper of tiny coffees, ever fail to answer a student’s question? Gradually, though, I realized that even when I didn’t have the knowledge my students sought, I typically knew how to find it. Moreover, I could teach students how to find and interpret that knowledge themselves.

The point for teachers of History of all stripes, I think, is to find comfort in the discomfort of branching out into the unknown. All of us are learning right along with our students and that’s how it should be. After all, the objective of any school or university is to build an open society that asks questions, fosters lifelong learning, and enables the sharing of knowledge. That’s what we do here and doing it well is as much about not knowing everything as it is about knowing anything at all. To be effective teachers, we must feel free to honestly say, “I don’t know,” and follow it up with a spirited, “But let’s find out.”

***

Elizabeth O’Brien

This semester I am TAing for a course designed to introduce students to the history of U.S. relations with Latin America. About half of the students are freshmen and most have very little knowledge of Latin American history. During discussion, some students requested information regarding the colonial “caste” system, which was mentioned in the readings but not explained. After class I decided to look online for some further reading for them.

It was very difficult to identify an accurate and academically rigorous article that was accessible for lower-division undergraduates. First, I looked at several websites, but I could not use them due to blatant historical inaccuracies. Then I skimmed a few full-length scholarly articles, but they were far too dense and lengthy for the students.

I realized that Not Even Past was a perfect source for the concise and accessible explanation that I needed. I found an article by Dr. Susan Deans-Smith, “Casta Paintings,” which clearly explained how seventeenth and eighteenth-century authorities sought to define, label, and categorize the offspring of Spaniards, Indigenous natives, and Africans. They developed an intricate “caste system,” which was represented in paintings that depicted mixed racial groups. Deans-Smith’s article was complete with images. For example, one painting showed a Spanish man, his Mestiza (Spanish and Indigenous) wife, and their “Castiza” daughter. Several students reported that they read the piece and emerged with a much better understanding of racial and social categories in the history of Latin America.

***

Cacee Hoyer

Top Five Experiences as a TA

#5: A student wanted to meet to discuss her exam. During the almost half-hour long discussion, the student contradicted every comment I had made on her paper. I coolly tried to explain why she had lost points for this or that and she consistently insisted I was wrong. Eventually, she gave up her debate tactics and just blurted out “well are you going to give me any points back or not!” I just stared at her and explained how I generally didn’t do that unless there was a blatant mistake. At which she responded, “then why are we even supposed to meet with you!” As she stomped away, I was saddened as I realized she was an honor student because she could play the game and work the system, however, she failed to learn how to love learning.

#4 A student emailed me to explain he was not able to turn in his assignment on time because he had spent the night in jail. After I explained this wasn’t a University sanctioned excuse, he eventually turned in the assignment. A few weeks later he approached me in class, introducing himself as the guy who had emailed about spending the night in jail. I thought I should point out to him that perhaps using that tagline earns him points with his friends, but that it doesn’t quite work that way with his TA.

#3 I was leading a discussion in class, which quickly ran out of control when one student who persistently claimed he liked to be “provocative,” made racially inappropriate references that set off another girl quite vocally. At one point I was afraid we were going to have an all out brawl! My head was spinning, and so was the class…right out of control. That was definitely a learning experience for me!

#2 On final exams, several students still refer to Africa as a country.

#1 A student practically tackles me when she gets her exam back. She had struggled on the first exam and had been working very hard, coming to office hours and emailing me constantly. She was so excited she almost knocked me down! But in a good way.

More to read on innovations in teaching history

Banner Credits:

Les Grande Chroniques de France (via Wikimedia Commons)

Gene Youngblood lecturing at Rochester Institute of Technology, 1982 (via Wikimedia Commons)