On the west side of the Denver Capital building stands a soldier atop a stone monument. The soldier is easily recognizable as a Civil War soldier with his rifle ready, sword at his side, his distinctive hat, and the gaze of a vigilant soldier, saddened to be fighting his brother and countrymen. Ari Kelman dedicates portions of his book, A Misplaced Massacre: Struggling Over the Memory of Sand Creek, to a discussion about the history of this Civil War monument. The monument was erected and dedicated in 1909. This date places the monument in a period of United States history that saw the rapid erection of monuments across the landscape. Americans had emerged from the smoke and haze of the Civil War into a brave new world of freed slaves, Indian wars, and reform movements. Memorialization allowed for the reinterpretation of the racially motivated fratricide and cleansing of the west. Instead memorializers could reforge the familial bonds of the Union in stone. Denver memorialized this glory with their Union Soldier statue and a plaque that proudly displays a list of all the battles and engagements of the Civil War that Coloradans participated in. Notably listed in the battles is Sand Creek.

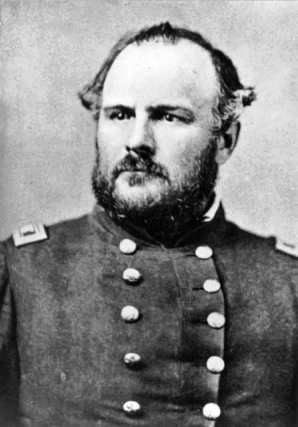

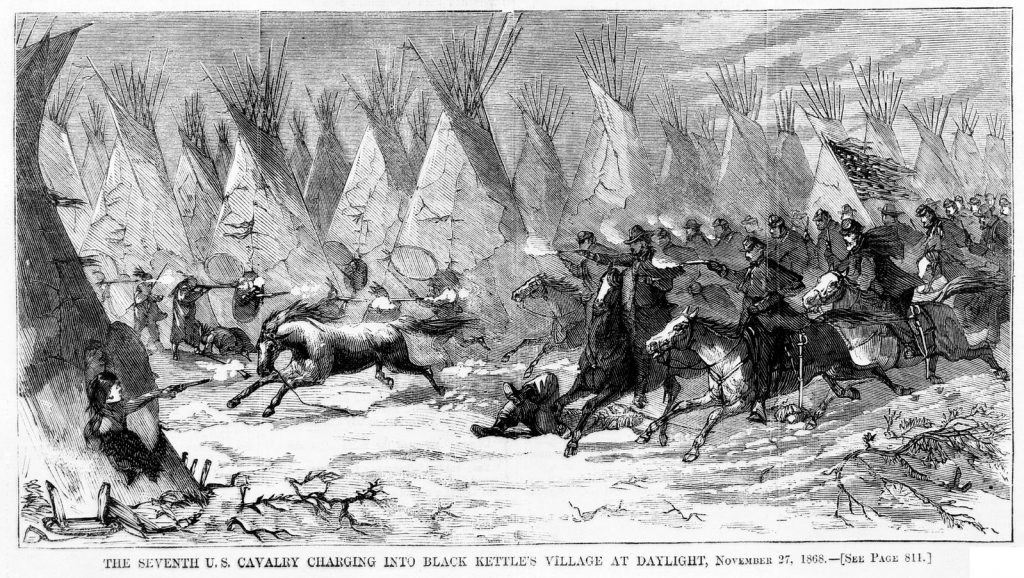

On November 29, 1864, Colonel John Chivington, with 700 men, attacked the Cheyenne and Arapahos camped peacefully along Sand Creek. Within the encampment was Black Kettle, a well known peace negotiator between the white settlers and the Indians. Black Kettle had recently returned to the Sand Creek camp, after concluding peace settlement negotiations at Fort Weld, where Chivington happened to be stationed. Upon realization of Chivington’s betrayal, Black Kettle immediately raised the American Flag and a white flag of surrender above his tipi, desperate to prove how those in the camp were friends of Americans and therefore peaceful. Chivington and his men took no heed of the raised flag, and continued the attack, killing not only men, but women and children who begged for mercy on their knees. Many ran to the sand beds along the creek where they burrowed into the sand, seeking cover from the sea of bullets. As the dust settled, 150 Cheyenne and Arapahos were dead. Chivington suffered the loss of ten men. His remaining 690 men proceeded to mutilate and desecrate the bodies of the deceased, with many keeping various body parts as grisly mementos.

As Kelman shows, immediately following the events of Sand Creek the public memory becomes cloudy and convoluted. For Chivington, the Union soldiers, and the American Nation, Sand Creek was a glorious battle in the story of westward expansion and the expulsion of the rebellious and violent Indians from the landscape. For the Cheyenne and Arapahos, Sand Creek was a brutal slaughter and massacre. One of Chivington’s men saw it the same way. Silas Soule was uneasy as he marched out on the day of the attack. When they arrived at Sand Creek, Soule refused to order his men to fire and he watched from the sidelines as the rain of bullets poured down on Black Kettle’s camp. Soule recorded the event in his letters, agonizing over his memories of that day.

A battle is often defined as an extended struggle between two organized armies. A massacre on the other hand is understood as the brutal and violent killing of multiple victims. The terms battle and massacre both carry heavy and violent meanings, but the picture they evoke are not the same. This difference in how to view the history and memory of Sand Creek coalesced around the Civil War monument in Denver in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The inclusion of Sand Creek in the list of battles and engagements on the monument at the Denver State Capitol projects an authority over the definition of the event and downplays its injustice by suggesting that there was a more even playing field between two opponents equally engaged. This leads the general public to believe that the band of Cheyenne and Arapahos provoked Chivington’s attack.

The debate over the monument was strikingly similar to the many debates we have seen in the past year over the many Confederate monuments across the American landscape. The central question is what do we do with these monuments that valorize highly politicized motivations but also provide a glimpse into the people, culture, and history of those who erected these very monuments? For historical preservationists, this question creates a crucial internal battle. Preservationists recognize the white veil that hides the ugly truth of the monument’s history and purpose. However, their desire to preserve leads them to a fiery inferno. Ultimately, preservationists cannot come to a consensus on what should be done, however. many advocate for at least reinterpretation of the monuments.

Reinterpretation was the path Colorado ultimately decided upon. A small plaque was attached, not to the monument itself, but to the brick knee-high wall around the monument. The plaque provides a small nugget of insight into the controversy over the memory of Sand Creek; and yet it still leaves open just enough ambiguity to allow a visitor to interpret Sand Creek as a battle.

Monuments have authority. They are literally etched in stone. They influence the way the public perceives and remembers history. After all, how do you argue with a giant bronze plaque attached to a monumental piece of stone, holding up a heroic citizen soldier who fought to preserve our Union?

Further Reading:

Ari Kelman, A Misplaced Massacre: Struggling Over the Memory of Sand Creek (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2013).

Thomas J. Brown, The Public Art of Civil War Commemoration: A Brief History with Documents (Boston: Bedford/St Martins, 2004).

Stephanie Meeks, “Statement on Confederate Memorials: Confronting Difficult History.”

Other Articles You Might Like:

On Flags, Monuments, and Historic Myths by Joan Neuberger

Reconstruction in Austin: The Unknown Soldier by Nicholas Roland

Paying for Peace: Reflections of the “Lasting Peace” Monument by Jesse Ritner