During the summer of 2016, we will be bringing together our previously published articles, book reviews, and podcasts on key themes and periods in the history of the USA. Each grouping is designed to correspond to the core areas of the US History Survey Courses taken by undergraduate students at the University of Texas at Austin.

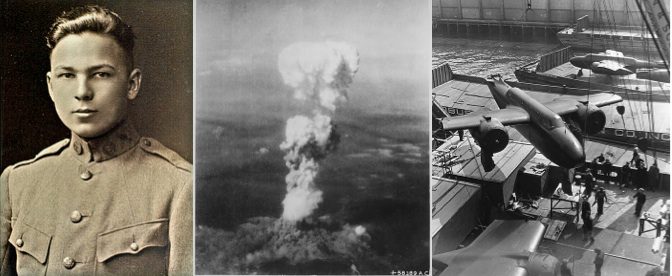

Andrew Villalon offers the stories of some World War I veterans, including Frank Buckles, the last American who served in the war.

Jacqueline Jones shares a personal story of a World War II love story, and a poem.

During World War II the United States shipped an enormous amount of aid to the Soviet Union through the Lend-Lease program, discussed on NEP by Charters Wynn. And here is a video to accompany the piece.

Bruce Hunt discusses the decisions and discussions that led the US to drop an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima, signaling the end of WWII.

And, Charlotte Canning traces the diplomatic role played by US theatre during the first half of the twentieth century.

Recommended Books:

Jermaine Thibodeaux recommends two books on black servicemen in World War I:

- Adriane Lentz-Smith’s Freedom Struggles: African Americans and World War I (Harvard University Press, 2009)

- Chad L. Williams’s Torchbearers of Democracy: African American Soldiers in the World War I Era (University of North Carolina Press, 2010).

Turning to WWII and the Pacific, Michael Stoff recommends a readable tale of Olympic runner Louis Zamperini, a Japanese prisoner of war: Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption by Laura Hillenbrand (2010)

Emilio Zamora talks about his study, “Claiming Rights and Righting Wrongs in Texas; Mexican Workers and Job Politics during World War II” (Texas A&M University Press, 2009)

Lior Sternfeld reviews The Wilsonian Moment, by Erez Manela (Oxford University Press, 2007).

Yana Skorobogatov recommends The Atomic Bomb and the Origins of the Cold War, by Campbell Craig and Sergey Radchenko (Yale University Press, 2008)

Michelle Reeves suggests Henry Wallace’s 1948 Presidential Campaign and the Future of Postwar Liberalism, by Thomas W. Devine (University of North Carolina Press, 2013), and Divided Together: The United States and the Soviet Union in the United Nations, 1945-1965, by Ilya Gaiduk (Stanford University Press, 2013).

And finally, check out these recommended books on WWI, including José A. Ramírez’s To the Line of Fire, Mexican Texans and World War I (2009) and these on WWII, including David Kennedy, The American People in World War II (Oxford University Press, 2003).

From 15 Minute History:

America’s Entry in to World War I

World War I ended the long-standing American policy of neutrality in foreign wars, a policy seen as dating back to the time of George Washington. What forces conspired to bring the United States into World War I, and what was the reaction at home and abroad?

Historian Jeremi Suri walks us through the events and processes that brought the United States into The Great War.

The U.S. and Decolonization after World War II

Following World War II, a large part of the world was in the hands of European powers, established as colonies in the previous centuries. As one of the nations that came out on top of the geo-political situation, the United States was looked to with hope by aspiring nationalist movements, but also seen as a potential source by European allies in the war as a potential supporter of the move to restore the tarnished empires to their former glory. What’s a newly emerged world power to do?

Guest R. Joseph Parrott takes a look at the indecisive position the United States took on decolonization after helping liberate Europe from the threat of enslavement to fascism.

Eugenics

Early in the twentieth century, governments all over the world thought they had found a rational, efficient, and scientific solution to the related problems of poverty, crime, and hereditary illness. Scientists hoped they might be able to help societies control the social problems that arose from these phenomena. All over the world, the science-turned-social-policy known as eugenics became a base-line around which social services and welfare legislation were organized.

Philippa Levine, co-editor of a newly published book on the history of eugenics, explains the appeal and wide-reaching effects of the eugenics movement, which at its best inspired access to pre-natal care, access to clean water, and the eradication of harmful diseases, but at its worst led to compulsory sterilization laws, and the horrific experiments of the Nazi death camps.

To learn more on Eugenics in the USA, and beyond, check out Philippa Levine’s article ‘Eugenics Around the World’ on NEP.

Teaching the World Wars:

Joan Neuberger discusses the Harry Ransom Center’s The World at War, 1914-1918 exhibition, and talks to the curators of the exhibition.

Sarah Steinbock-Pratt discusses UT’s Normandy Scholar Program on World War II and recommends some great WWII films.

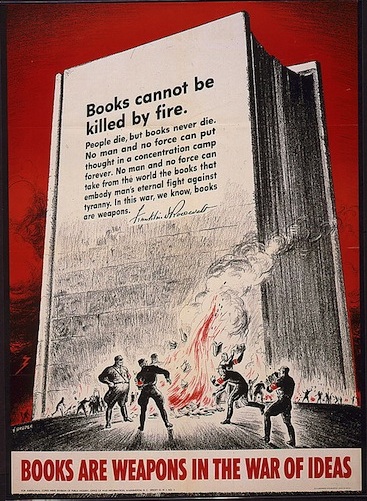

You may also like Joan Neuberger’s exploration of World War II images on Wikimedia Commons: Part One and Part Two.