Sitting in the archive, thumbing through delicate sixteenth-century documents and trying to decipher centuries old paleography, it is easy to forget that the city outside breathes history too. Sources are mesmerizing and reading them is addictive and satisfying. But the life of a researcher can begin to feel like scurrying through tunnels made of words, dates, and images spread across paper, or on the screen. Occasionally, when one comes up for air and walks through the streets of a city, the mind wonders in creatively productive ways and the subjects of research can appear in unusual places far away from the archive. These moments remind us that real people walked the same ground centuries before. That is what happened to me during my first research trip to Seville while researching at the General Archive of the Indies, the enormous bureaucratic repository of documents related to Spain’s overseas kingdoms.

It was a boiling hot day and I decided to take a break from my work. Offering a lazy “ciao” to the security guard on the way out, I walked into the wall of heat that surrounded this beautiful Andalus city in the summer. Strolling around the magnificent cathedral that integrates Moorish and Catholic elements, scurrying between the shadows provided by palm trees, I headed up one of the gaudy shopping streets that act as tributaries from the city’s historic center. Undistracted by the pulsating music and new flowery patterned shirts on display, my mind remained fixed on the sixteenth-century English merchant and botanist John Frampton, who had lived in the city nearly five centuries previously and was the subject of my research.

Frampton’s life in Seville had been eventful. He traded with the cosmopolitan merchant community, established friendships with the English expats of Southern Iberia (much like myself), and was tried by the Inquisition for having a copy of a forbidden book (luckily, not much like myself). Allegedly his English friends had watched him carried into the city for his trial hanging from the underbelly of a donkey. Frampton was also the great translator of six important Spanish works on the New World, most notably the huge compendium of medical discoveries collected by the famous Spanish botanist Dr Nicolás Bautista Monardes, resident of this city.

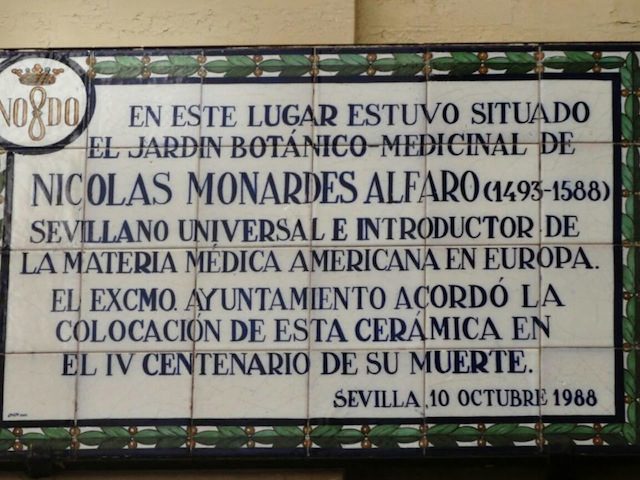

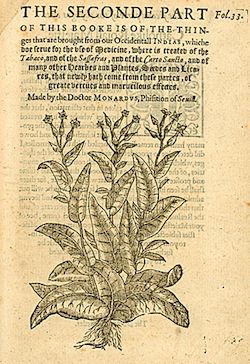

Dr Monardes was curious by nature. A Genoese physician by training, he became fascinated by the medical potential of the plants and herbs used by indigenous people across the Atlantic in the New World. As ships returning from their lengthy voyages sailed up the Guadalquivir River from the Atlantic and settled on its banks, Dr Monardes would purchase the natural products and seeds they brought back and begin experimenting. He sent reports of his discoveries to King Phillip II and he published them in multiple editions. By doing so, he brought the extraordinary pharmacopeia and medical knowledge of the people of South America to the reading public in Europe. Yet, as always seems to be the case, the indigenous groups received little credit as Monardes and others with connections to notables and access to publishers took all the plaudits. As a result of this all-too-common maneuvering, Monardes has come down to us as a key player in the sixteenth-century Iberian scientific revolution.

As I walked, my mind moved into a new gear as I considered how the lives of these historical subjects intersected with the sixteenth-century scientific revolutions I had read about. A recent pair of studies focused on London and Seville came to mind. Commonly associated with the intellectual communities of Northern Europe, studies by Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra and Antonio Barrera-Osorio have reconsidered the scientific revolution in terms of place, period, and the scope of historical actors and disciplines. These books questioned the importance of “Great Men” such as Galileo by expanding definitions of science from math and physics to human approaches to nature. They highlighted the roles played by artisans and merchants during European overseas expansion in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. As merchants brought natural products and knowledge to European ports, new systems of organization, experimentation, and proof developed. In their accounts, Seville was the bustling laboratory of Europe’s first scientific revolution, and it was here that the English expat merchant Frampton discovered and most likely met the Genoese expat naturalist Monardes.

Frampton’s Joyfull Newes Out of the Newe Founde World, his translation of Monardes’ treatise became a best seller in Elizabethan London, testament to the ways the scientific culture of Iberian cities like Seville sparked a fascination with the New World in England. The book formed part of a larger corpus of English language translations of Spanish scientific texts completed by merchants who had spent most of their lives in Iberian port cities. These men learned Spanish, married locally, and integrated into local societies, until the reformation and heightening imperial rivalries sent them home to England. Back in Albion knowledge became their new commodity and their language skills offered them a chance to rebuild a life as translators in the service of the English crown. But it was on the bustling streets of Seville that he learned Spanish and discovered the works of Monardes.

Many years later, the streets still bustled as I walked past a delicious looking ice-cream shop and remembered that Frampton’s translation had also been cited in Deborah Harkness’ recent study of a vibrant scientific community in London between 1550 and 1610. Harkness discovered nearly two thousand artisans and “middling-sorts” conducting experiments in London’s streets during this period. Fascinated by the natural world and commercial opportunities, this community formed the backbone of London’s Elizabethan Scientific Revolution. These early men of science disappeared from history only because they failed to publish their discoveries. Instead, now well-known figures like the herbalist John Gerald and Francis Bacon claimed ownership of their ideas through publications; reminiscent of the fate of indigenous medical knowledge at the hands of Monardes. Harkness introduces us to a number of fascinating individuals such as the naturalists of Lime Street and one Clement Draper whose “Prison Notebooks” demonstrate the existence of a cosmopolitan laboratory of scientific exchange and discovery in the King’s Bench Prison. Harkness downplays the significance of individuals, instead emphasizing the importance of London’s “urban sensibility” – its spirit of collaboration and exchange – in providing the conditions for the emergence of scientific culture. But was London’s “urban sensibility” so unique in this period?

I rolled this question around, turned a corner, and came to the end of the long shopping street. I paused for a moment to look at the faces staring out of a clock shop and thought about the precise scientific method that developed on these streets. I stepped back to take a photo and I happened to look up. Mounted there, above the ticking clocks, a small blue sign marked the botanical garden of none other than Dr Monardes. I tried to imagine what the site must have looked like as the doctor worked among his tropical plants. I thought of the magnificent gardens I had seen a few weeks before in the Alcazar, just around the corner. It was refreshing and exciting to stand so close to the place that Dr Monardes had conducted his experiments, and where John Frampton would no doubt have stood when admiring the work of the great scientist. It was in this moment, trying to imagine the life of these two individuals, that they came alive again, in my mind, as humans living in a dynamic world.

And now I found myself wondering how individuals like Frampton connected the sixteenth-century scientific revolutions of Seville and London. Frampton, like myself, lived between the English and Spanish worlds, happily content in either. Given the continuous movement of such merchants between the Anglo and Iberian worlds in this period, I began to consider how separate these worlds were, and whether the scientific revolution should be understood in relation to national or imperial frameworks. And with this new set of questions in mind, I retraced my steps back to the archive.

Sometimes it is best to give your eyes a break from the sources and go searching for history in the streets. When the city walls show you where it really happened, ideas spark and our connections with historical subjects are re-made.

You may also like:

Ernesto Mercado Montero discusses Ordinary Lives in the Early Caribbean: Religion, Colonial Competition, and the Politics of Profit, by Kristen Block (2012)

Mark Sheaves reviews Francisco de Miranda: A Transatlantic Life in the Age of Revolution 1750-1816, by Karen Racine (2002)

Bradley Dixon, Facing North From Inca Country: Entanglement, Hybridity, and Rewriting Atlantic History

Ben Breen recommends Explorations in Connected History: from the Tagus to the Ganges (Oxford University Press, 2004), by Sanjay Subrahmanyam

Christopher Heaney reviews Poetics of Piracy: Emulating Spain in English Literature (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013) by Barbara Fuchs

Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra discusses his book Puritan Conquistadors: Iberianizing the Atlantic, 1550-170 (Stanford University Press, 2006) on Not Even Past.

Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra reviews Shores of Knowledge: New World Discoveries and the Scientific Imagination (W.W. Norton Company, 2014)

Renata Keller discusses Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in the Americas, 1492-1830 (Yale University Press, 2007) by J.H. Elliott.

Further Reading:

Deborah Harkness, The Jewel House: Elizabethan London and the Scientific Revolution (Yale University Press, 2007)

Antonio Barrera-Osorio, Experiencing Nature: The Spanish American Empire and the Early Scientific Revolution (University of Texas Press, 2006)

Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra, Nature, Empire, and Nation: Explorations of the History of Science in the Iberian World (Stanford University Press, 2006)

_________________________________________________________________________________________

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.