Luanda and Benguela became the busiest, most profitable slaving ports in the transatlantic slave trade in the seventeenth century precisely because these two ports set up tribunals to hear tens of thousands of enslaved petitioners demand freedom. Paperwork in local tribunals set hundreds of thousands free, even at the risk of bankrupting powerful merchants. As petitioners litigated their freedom, the colonial state grew in legitimacy and bottom up support. Through petitioning and litigation, the peoples of Luanda and Benguela became active “Portuguese” vassals with rights. Those under the protection of the sovereign state became more than mere commodities while those outside became increasingly more vulnerable. Pervasively and paradoxically, the very consolidation of state legitimacy contributed to the expansion of the slave trade. After years of working in ecclesiastical, municipal, and state archives in Luanda, Rio, and Lisbon, Ferreria offers a major reconceptualization of colonialism and slavery itself. A better title for his book would have been: Petitioning Slaves and the Creation of the South Atlantic Slave Trade.

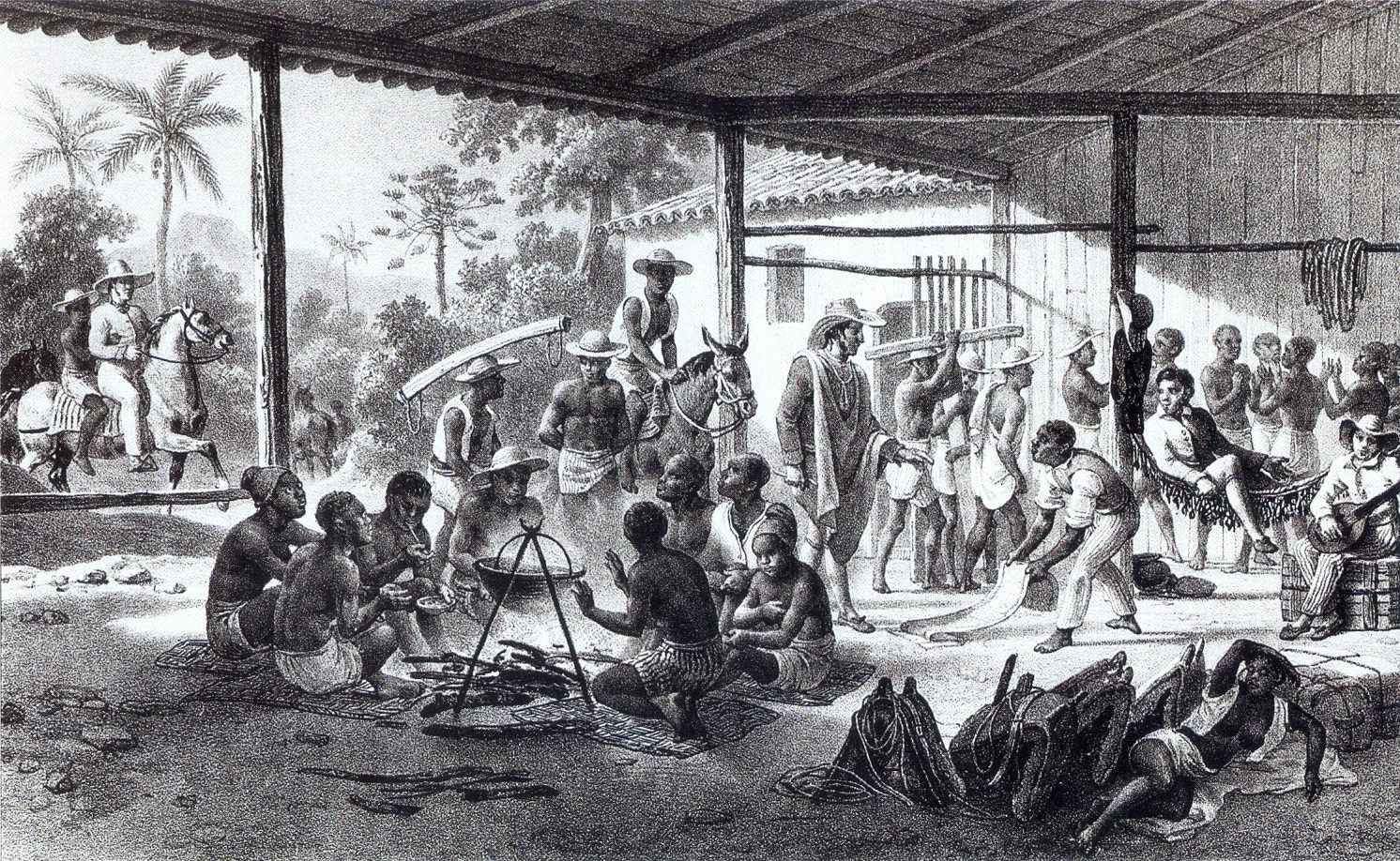

Angola was no more than these two relatively small ports of few thousand dwellers (moradores), each with strange connections to their hinterlands. Luanda and Benguela were overwhelmingly black and mulatto cities that engaged in formal ceremonies of protection and “transfer” of sovereignty with neighboring natural lords, sobas. The sobas offered labor, porters, and military aid to urban merchants (pumbeiros and sertanejos) and sheriffs (captães mores), the representatives of the Portuguese state, in exchange for a monopoly on the local redistribution of foreign commodities and support against their rivals. Sobas provisioned the trading caravans to the interior (sertões) with porters. The sobas also offered military aid to the cities when neighboring and distant sovereigns, including the Dutch, French, and British, threatened the ports.

This system of Portuguese sovereignty however was rather limited. To the north and south of Luanda and Benguela lay independent polities that for nearly three hundred years remained impervious to all threats of violence and negotiations. The degree of coastal isolation of these two ports was striking. Given the nature of maritime currents, Benguela and Luanda communicated much more easily with merchants in Rio (Brazil) than with one another. For nearly three centuries there were no roads connecting Luanda and Benguela. Like in the north and south, the eastern, interior frontiers of both cities ended where the independent Imbangala kingdoms began. The frontier was dotted with “forts,” or presidios, that were primarily trading centers: Indian cottons, Brazilian cachaça, and gunpowder for slaves. Within these narrow horizontal coastal-eastern corridors, the ports held loose control over the local natural lords, sobas, sworn to vassalage.

Ferreira describes how the expansion of trade within Luanda and Benguela’s subject territories led to the enslaving of vassals. As commodities arrived and credit expanded, so too did pawnship. Debtors would offer family members and subordinates as slaves to merchants. Sobas would also punish civil and criminal cases, particularly witchcraft, with slavery. This system benefitted merchants who did not have to rely on interior trading fairs to obtain chattel from independent kingdoms. Yet, at the same time, the Portuguese crown empowered local judges to set up tribunals to secure the rights of all vassals. Ferreria describes the workings and evolution of the Tribunal de mucanos in detail, offering a mind bending account of bottom up participation through paperwork.

Mucanos were petitioners who orally pleaded in front of sobas and capitães mores for freedom when wronged. Slowly, oral petitions became written, local custom codified, local decentralized decisions centralized, and corrupted local judges overseen by outside referees. Ferreria describes how the tribunal de mucanos, originally under the control of mercantile interests and self-interested local lords, evolved into a tribunal controlled by bishops (junta das missões). The juntas would have priests as translators-cum-official legal intermediaries (inquiridor das libertades), scribes (escrivão), registries (livro branco), and archives. Priests would become accountants, collecting the royal quinto (20% tax) after having properly ascertained who was rightfully enslaved. In practice, the job of the junta became one of distinguishing between outsiders from the sertòes, who could be enslaved, from the internal vassals who could not. More importantly, after baptizing the properly enslaved, priests would use the body of slaves to document the act of royal authorization and baptism by fire branding chattel. Slaves leaving Angola would carry two other fire marks as notarial documents: the originating and the receiving merchants’. Ferreria also shows that local decisions taken by the local rural tribunals would evolve into a hierarchical system of urban appellate courts, moving petitions from magistrates (ouvidor) to the governor (ouvidor geral) to Lisbon. There were slaves who sent petitions to Lisbon to appeal. Some even appeared in Lisbon in person.

Ferreria shows that in the second half of the eighteenth century the debate over the right to enslave vassals evolved, particularly as the governor Miguel Antonio Mello argued that the same rules to judge the wrongful enslavement of soba vassals should also apply to processes within the sovereign kingdoms of the sertões. All slaves, regardless of their origin, should have the right to appeal. Mello’s good intentions were not to last beyond his time in office. Mello, nevertheless, waived all fees to mucanos in judicial procedures.

In Luanda and Benguela, race was meaningless except as marker of social status, which was signified through clothing. Many petty merchants were slaves-for-hire, retailers (quissongos), moving cachaça, guns, and Indian cottons into the trading fairs (feiras) in the interior sertões while bringing back caravans of slaves. Many settlers (moradores) of the ports were ladinos, that is urban slaves who enjoyed extraordinary freedoms, including often the right to move to Brazil as servants, petitioners, and traders. Merchants and captains were largely exiles and criminals, degredados, from Brazil. Black settlers and ladinos were considered “white,” but so too were the vassals of allied sobas who through trade acquired European shoes: Negros calçados would petition to be exempted from tribute as porters and be treated as “white.” Female slaves who amassed considerable fortunes as market women (quitanderas) also became free “white” settlers. This was a world of both strict social hierarchies and dizzying social mobility.

One of Ferrerira’s most intriguing contributions is to demonstrate the peculiar relation of Brazil and Angola, one that almost entirely excluded the Portuguese. If Angola was a colony, it was Rio’s and Minas Gerais’s. Beginning in the late seventeenth century, the expansion of gold mining in Minas led to the growth of Brazilian involvement in Luanda and Benguela. Merchant-pombeiros and sheriffs-capitães mores were often exile-degredados from Brazil. Luanda and Benguela settlers sent their kids to be educated in Rio. Many acquired trades in Brazil and came back as carpenters and tailors. When Brazil declared independence in 1822, the Portuguese remained fearful for several decades of repeated conspiracies to unite Angola to the new Brazilian empire. The case of Angola demonstrates that early modern monarchies were indeed polycentric. The center of gravity often lay in America, not Europe.

This extraordinary, eye-opening book not only illuminates the distinct nature of South Atlantic systems of slavery, connecting Rio to Luanda and Benguela, a system that accounted for at least one third of all the slaves brought to the Americas. It also throws light on the role of slave petitioning in securing legitimacy and political resilience There were extraordinary parallels between the Tribunal de mucanos in Angola and the Republica de indios in Spanish America. In both cases, the state invested heavily in protecting nonwhite vassals from mercantile predation. In doing so, the system grew in legitimacy and longevity. The true paradox of modernity might not be that white freedom was possible because there was black slavery, as Edmund Morgan argued in American Slavery, American Freedom. The true paradox might well be that slavery grew and multiplied precisely because there were tens of thousands of slaves who petitioned and obtained their freedom.

You May Also Like:

Slavery and Race in Colonial Latin America

Slave Rebellion in Brazil

Also by Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra:

From There to Here: Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra

Puritan Conquistadors

Jerónimo Antonio Gil and the Idea of the Spanish Enlightenment

Promiscuous Power: An Unorthodox History of New Spain