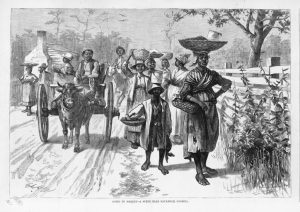

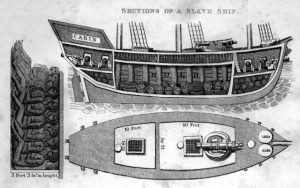

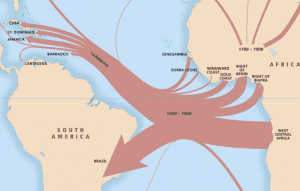

Slavery and the slave trade transformed the world. According to the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, 12.5 million African women, men and children were shipped across the Atlantic to North and South America as slaves. As many as 2 million died in transit. In recent years, historians have started to investigate slavery in other contexts. While the Atlantic slave trade was vast, slavery was a truly global phenomenon appearing in diverse regions. Not Even Past offers a range of book reviews, articles, and podcasts related to slavery. They engage issues as varied as capitalism, labor, race, gender, and love, among others. We hope this collection can act as a resource for teachers looking to build their curriculum, and portal for all readers interested in new writing and scholarly debates

Books on Slavery

Blacks of the Land: Indian Slavery, Settler Society, and the Portuguese Colonial Enterprise in South America by John M. Monteiro (2018)

Black Slaves, Indian Masters: Slavery, Emancipation, and Citizenship in the Native American South, by Barbara Krauthamer (2013)

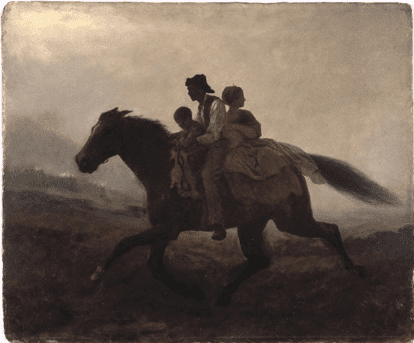

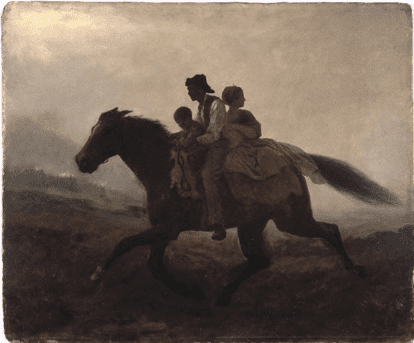

Driven Toward Madness: The Fugitive Slave Margaret Garner on the Ohio by Nikki M. Taylor (2016)

Cross-Cultural Exchange in the Atlantic World; Angola and Brazil during the Era of the Slave Trade by Roquinaldo Ferreira (2012)

Madeleine’s Children: Family, Freedom, Secrets and Lies in France’s Indian Ocean Colonies, by Sue Peabody (2017)

Empire of Cotton: A Global History by Sven Beckert (2015)

Slaves and Englishmen, by Michael Guasco (2014)

Quilombo dos Palmares: Brazil’s Lost Nation of Fugitive Slaves, by Glenn Cheney (2014) – by Edward Shore

Slave Rebellion in Brazil: The Muslin Uprising of 1835 in Bahia by João José Reis (1993) – by Michael Hatch

Nat Turner: A Troublesome Property (2002) – by Daina Ramey Berry and Jermaine Thibodeaux

Articles on Slavery

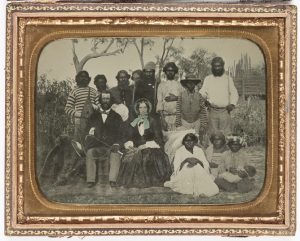

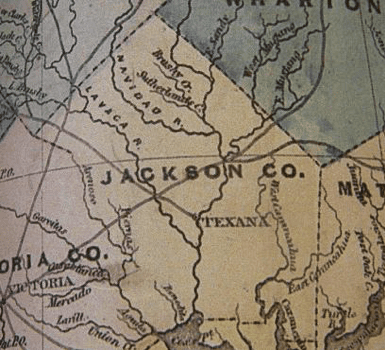

Love in the Time of Texas Slavery – by María Esther Hammack

White Women and the Economy of Slavery – by Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers

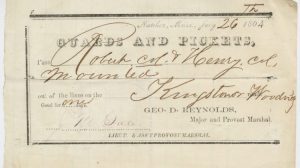

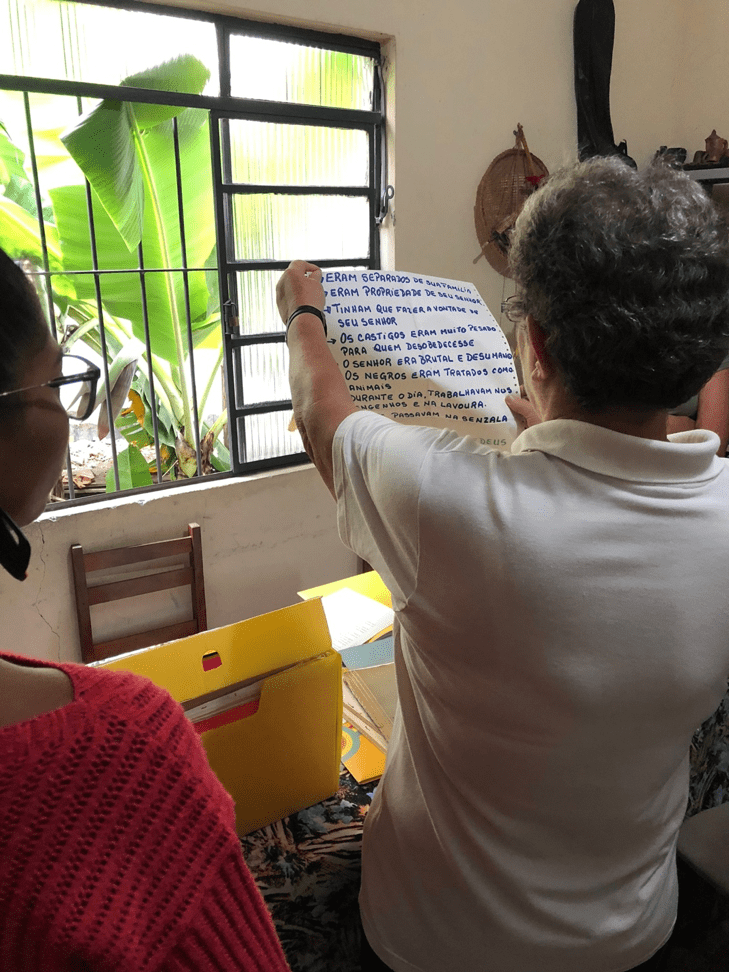

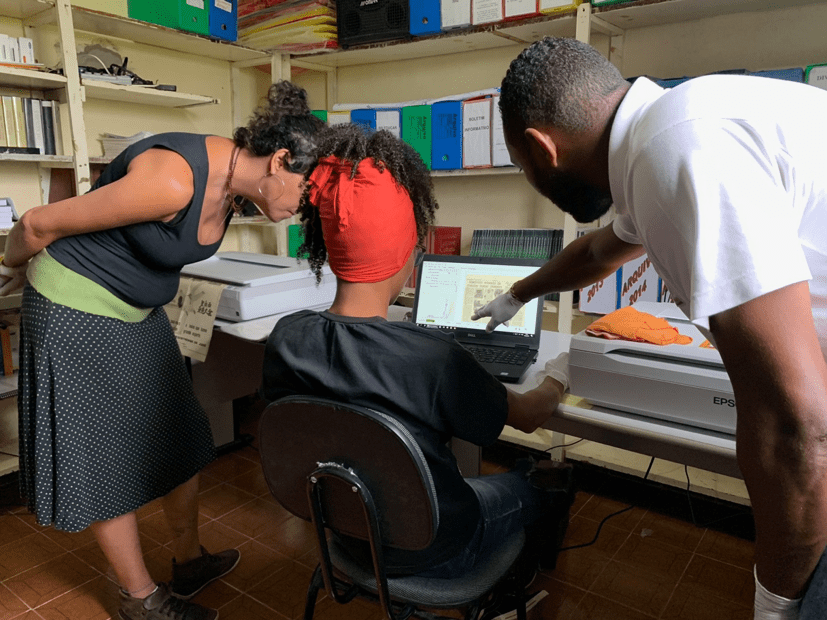

The Public Archive: The Paperwork of Slavery – Galia Sims

US Survey Course: Slavery

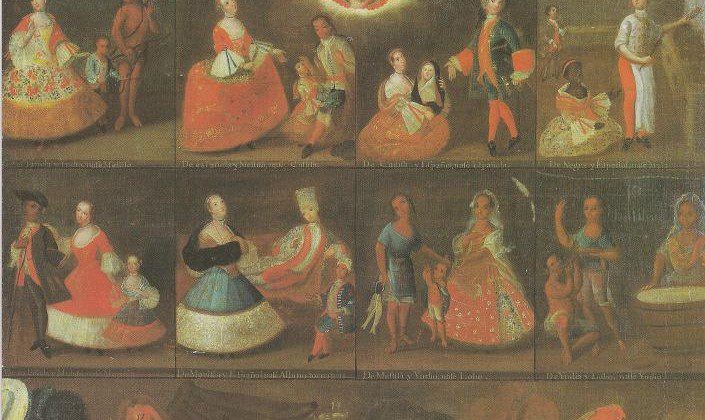

Slavery and Race in Colonial Latin America

Slavery and its Legacy – by Mark Sheaves

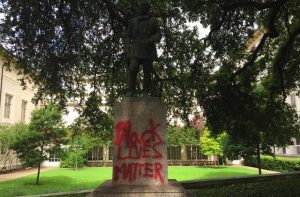

#Blacklivesmatter Till They Don’t: Slavery’s Lasting Legacy – by Daina Ramey Berry and Jennifer L. Morgan

Slavery in America: Back in the Headlines – by Daina Ramey Berry

Andrew Cox Marshall: Between Slavery and Freedom in Savannah – by Tania Sammons

Slavery and Freedom in Savannah – by Leslie M. Harris and Daina Ramey Berry

The Cross-Cultural Exchange of Atlantic Slavery – by Samantha Rubino

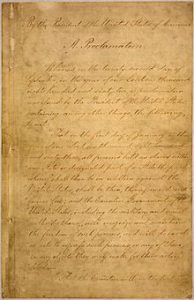

Visualizing Emancipation(s): Mapping the End of Slavery in America – by Henry Wiencek

Daina Ramey Berry on Slavery, Work and Sexuality

Great Books on Slavery, Abolition, and Reconstruction – by Jacqueline Jones

The Littlefield Lectures: The Van and the Read: Abolitionists Roots of Radical Reconstruction (Day 1)

The Littlefield Lectures: The Van and the Rear: Abolitionists Roots of Radical Reconstruction (Day 2)

The Price for Their Pound of Flesh – by Daina Ramey Berry

The Illegal Slave Trade in Texas, 1808-1865 – by Maria Esther Hammack

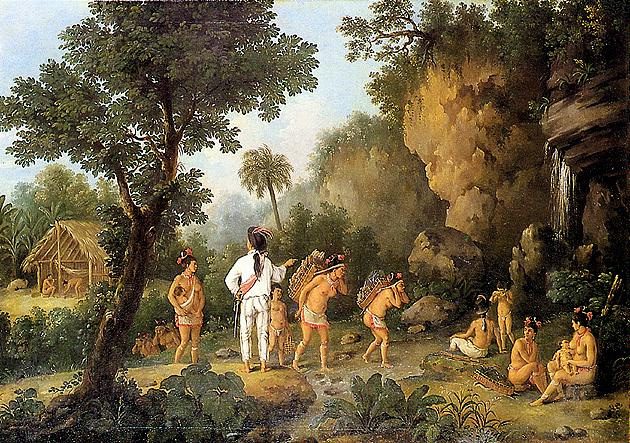

Glimpsed in the Archive and Known no More: One Indian Slave’s Tale – by Sumit Guha

Mapping the Slave Trade: The New Archive (No. 10) – by Henry Wiencek

The Emancipation Proclamation and its Aftermath

Work Left Undone: Emancipation was not Abolition – by George Forgie

“Captive Fates: Displace American Indians in the Southwest Borderlands, Mexico, and Cuba, 1500-1800” – by Paul Conrad

Film Reviews

“12 Years a Slave” and the Difficulty of Dramatizing the “Peculiar Institution” – by Jermaine Thibodeaux

Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained (2012) – by Daina Ramey Berry

Great Books on Enslaved Life and Labor in the US – by Daina Ramey Berry

Podcasts on Slavery

Episode 120: Slave-Owning Women in the Antebellum U.S.

Episode 114: Slavery in Indian Territory

Episode 105: Slavery and Abolition

Episode 98: Brazil’s Treatro Negro and Afro-Brazilian Identity

Episode 88: The Search for Family Lost in Slavery

Episode 70: Slavery and Abolition in Iran

Episode 54: Urban Slavery in the Antebellum U.S.

Episode 42: The Senses of Slavery

Compiled by Jesse Ritner, updated by Adam Clulow