Governing is complicated. It requires an understanding of both top-tier policy and a recognition of changing circumstances over time. It also involves a comprehensive workforce, who perform different tasks according to their position in the larger hierarchy. The Spanish monarchy ruled over territories stretching from the Caribbean to the islands of Asia, and to the southernmost point of South America, for over 300 years. During that period, there was no neat transference of authority from the court, located in Madrid, to the civilizations of the Americas. Instead, a confluence of contradictory voices and choices paved the way for Spanish imperial rule.

“Bureaucracy on the Ground in Colonial Mexico” is a digital exhibition created to help scholars and the public access the lived experience of colonial rule. Its newest features allow for further exploration of the many actors involved in the processes of governance.

The objective of this project is to follow bureaucratic function on the ground. In partnership with the Benson Latin American Collection, I created an interactive digital exhibition on the 1765 visita, or royal inspection, of New Spain. The visita examined local institutions, evaluated economic policies, and reorganized society in a broad display of royal authority. This procedure helped the king implement widespread political, economic, and social reform in this territory in order to tighten control and increase efficiency. It set the precedent for changing policies throughout the empire over the next several decades.

Designed for a non-specialist audience, the exhibition explores the timeline, spatial breadth, and procedure of the inspection, by providing access to digital versions of the original documents produced by the royal inspection visita. The project provides an accessible forum for understanding how the lengthy and expensive process of royal governance effectively fostered relations between the ruling government in Spain and its many different constituencies on the ground in the Americas.

The site now offers full transcriptions of all the documents. Users could previously read the documents in their original form from high-quality images. Now they can dive deeper into the significance of the text itself. The kinds of words that Spanish officials were using– and the patterns in which they used them–help reveal the way that the Crown’s authority manifested itself locally.

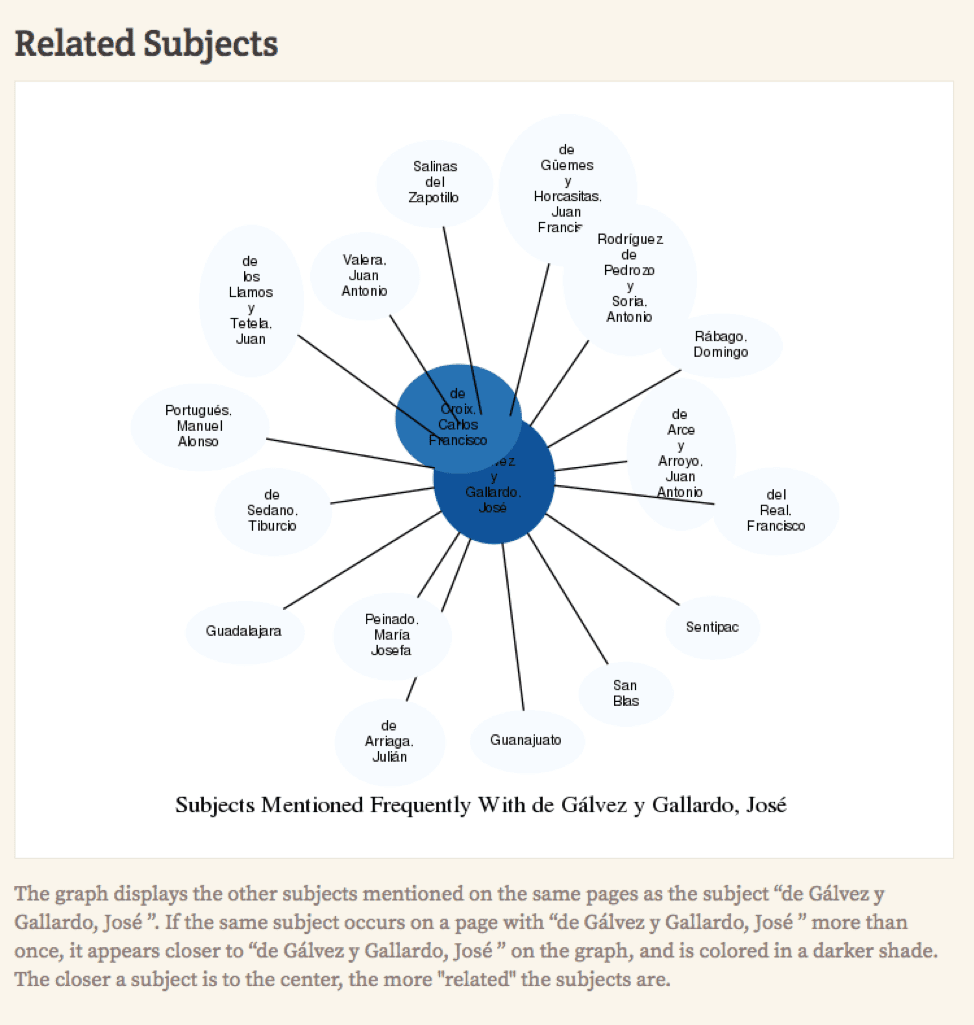

Closer textual analysis also helps identify the multiple actors involved in this process. The Spanish monarch, Charles III, had designated José de Gálvez as the inspector general, or visitador. However, at every point, the inspection required the assistance of a wide variety of local officials, from priests to supervisors at the tobacco factory. Gálvez also frequently consulted with the viceroy, Carlos Francisco de Croix. These personal connections are significant because they reveal both the tensions and the cooperation that royal administration could meet in the Americas.

The new features of the “Bureaucracy on the Ground” site help make the obscure topic of imperial governance more accessible. For the Spanish Crown, 300 years of colonial rule depended on more than the faraway king’s decisions. It was the people on the ground who made the bureaucracy work, and this project aims to acknowledge the many forms of their participation in the process of imperial rule.

This project has received support from Professor Joan Neuberger, LLILAS Benson Digital Scholarship Coordinator Albert Palacios, and the UT Digital Writing and Research Lab

Also by Brittany Erwin

The Museo Regional de Oriente in San Miguel, El Salvador

The National Museum of Anthropology in in San Salvador

Review of The Archaeology and History of Colonial Mexico by Enrique Rodríguez Alegría (2016)

History for Us at the El Paso Museum of History

Other Article You Might Like

Digital Teaching: Mapping Networks Across Avante-Garde Magazines

Digital Teaching: The Stalinist Purges on Video

Digital Teaching: A Mid Semester Timeline