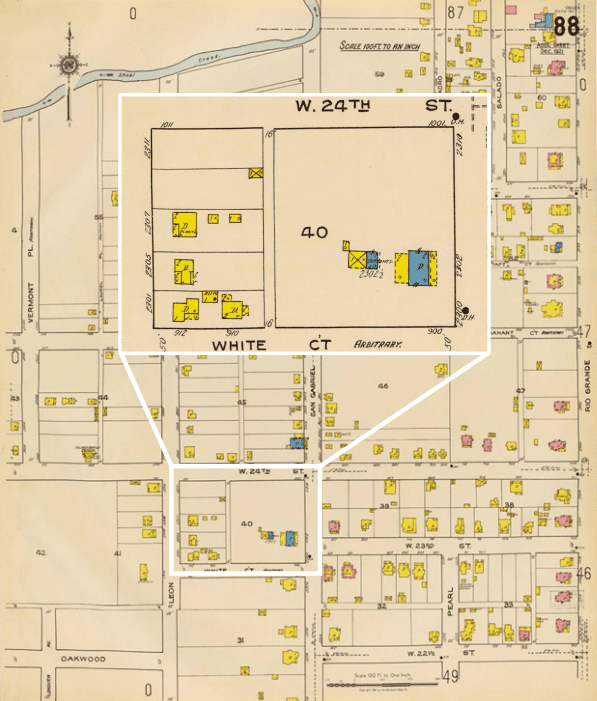

On November 6, 1855, Washington Hill commissioned Abner H. Cook to build a southern plantation house in Austin, Texas. The Texas Historical Commission reported that “the property worth $900 in August 1855 was worth $8,000 when Hill paid his taxes for 1856.” When the two-story limestone home was completed, Hill had greatly overextended his financial resources. In an attempt to retain the property, Hill sought tenants to help with his costs. Fortunately for him, the Texas Legislature would approve funding for a program that would help. In 1856, the same year Hill’s home was completed, the legislature voted to found an Asylum for the Blind. Austin’s asylum would provide initial financial relief to Hill, but it also led to the use of enslaved people on his property.

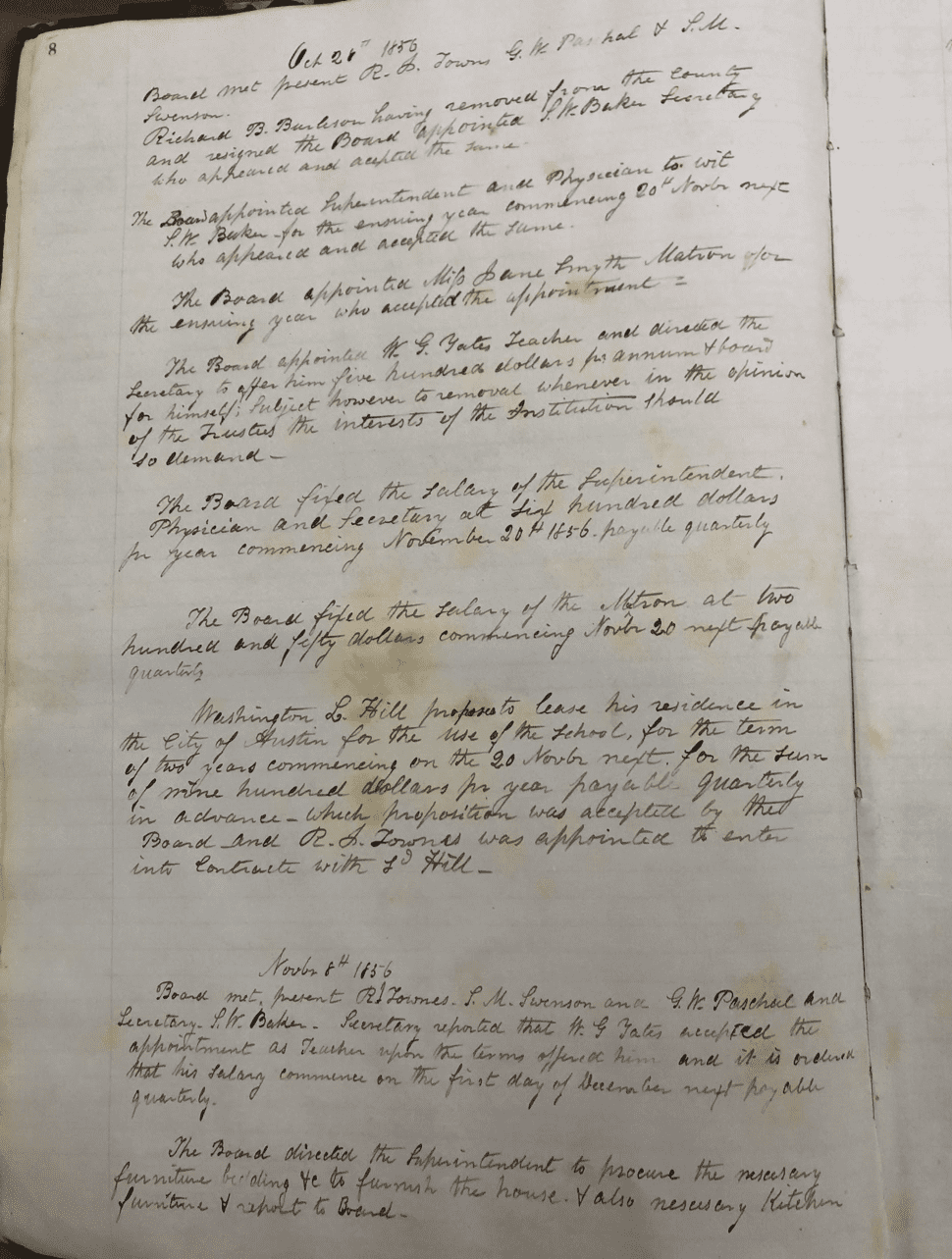

From 1856 to 1919, the Texas State Asylum for the Blind took copious and painstakingly detailed notes of all business-related meetings. One of the earliest entries recorded the asylum entering into a contract with Washington Hill for the purpose of using his property. An entry made on October 26, 1856 states:

Washington L. Hill proposes to lease his residence in the city of Austin for the use of the school for the term of two years commencing on the 20 Nov[em]b[e]r next for the term of nine hundred dollars per year payable quantity in advance — which proposition was accepted by the Board and R. L Townes was appointed to enter into contract with L. Hill.[1] (See below)

The legal stipulation that he receive the entire year’s payment from the asylum in advance speaks to the urgency of Hill’s financial situation. Nonetheless, having extended control of his property to the School for the Blind allowed for the school to do what was necessary to conduct business.

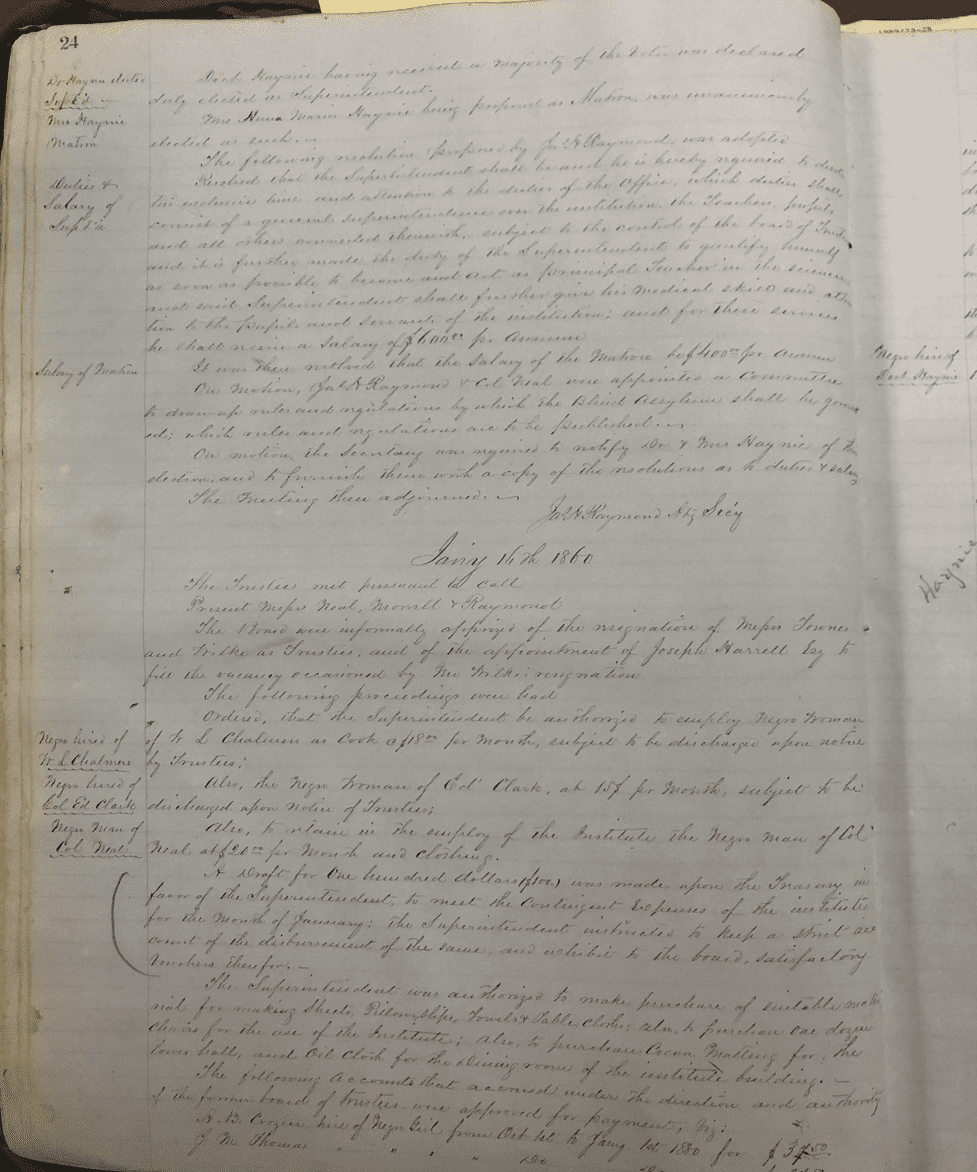

Meeting files for 1860 illuminate how agents of the Texas State Legislature and their enslaved persons were vital to the school’s successful operation. Several entries that took place during a meeting on January 16, 1860 reveal both the enslaver’s name and the role their enslaved persons were to have at the School for the Blind. The meeting file states:

“The following proceedings were had. Ordered, that the Superintendent be authorized to employ Negro woman of W L Chalmers as cook $18.00 per month, subject to be discharged upon notice by trustee: Also, the negro woman of Ed Clark, at $15 per month, subject to his discharge upon notice of Trustees: Also, to retain in the employ of the institute the Negro man of Col Neal at $20 per month and clothing. . . . The salary for the negro girl belonging to Doch Maynire was filed at $10 dollars per month instead of $12 dollars as first agreed upon. . . . The meeting then adjourned.[2] (See below)

The two women, one girl, and one man mentioned at this meeting reveal the presence of four enslaved people laboring at Austin’s School for the Blind in 1860. In all these instances, the school paid each enslaver a monthly rate to use their enslaved persons for the benefit of the school’s operation. While one enslaved woman was reported to have served as a cook, the role of the others was not mentioned. The identity of two of the men responsible for the renting of these enslaved people, however, is revealed by Texas’ ninth Governor, Francis Richard Lubbock in his memoirs. W. L. Chalmers and Edward Clark were key members of the Texas State Legislature. Lubbock identified Chalmers as an “assistant clerk” of the Seventh Legislature, in 1857 and “chief clerk” of the Ninth Legislature in 1861.[3] Edward Clark was the “Secretary of State” to Governor Elisha M. Pease from 1853-1857.[4] Clark would serve as the Lieutenant Governor of Texas from 1859-1861 and the Confederate Texas Governor in 1861. Thus, the property currently known as the Neill-Cochran house was once a place where both enslaved people and the highest-ranking state officials, converged to ensure the well-ordered functioning of the Texas School for the Blind.

Sources for this article:

[1] An Inventory of School for the Blind and Visually Impaired Meeting Files 1856-1919, 1979-2015, Volume 1989/073-28, Texas State Asylum for the Blind/Blind Institute/Texas School for the Blind, 1856-1919, Texas State Library and Archives Commission, Austin, TX.

[2] Ibid, 24-25

[3] Frances Lubbock, Six Decades in Texas: Or Memoirs of Frances Richard Lubbock, Governor of Texas in War Time 1861-1863, Austin: B. C. Jones & co., printers, 1900), 223, 329.

[4] Ibid., 195.

An Inventory of School for the Blind and Visually Impaired Meeting Files 1856-1919, 1979-2015, Volume 1989/073-28, Texas State Asylum for the Blind/Blind Institute/Texas School for the Blind, 1856-1919, Texas State Library and Archives Commission, Austin, TX.

Evelyn M. Carrington. The Neill-Cochran Museum House, 1855-1976: A Century of Living from Texas History. Waco, TX: Texian Press for the National Society of the Colonial Dames of America in the State of Texas, 1977.

Kenneth Hafertepe. Survey and Multiple Property Nomination of Abner Cook Structures in Austin. 1989.

Francis Richard Lubbock. Six Decades in Texas; or, Memoirs of Francis Richard Lubbock, Governor of Texas in War Time, 1861-63. Edited by Cadwell Walton Raines. Austin: B. C. Jones & Co.,1900.

You might also like:

The Blackwell School in Marfa, Texas

Fandangos, Intemperance, and Debauchery

Paying for Peace: Reflections on the “Lasting Peace” Monument

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.