By Alejandra Garza and Maria Esther Hammack

Controversies surrounding textbooks are nothing new, especially in Texas. For years, textbook selection in Texas has grabbed headlines and generated great discontent and debate. Textbooks adopted by the Texas State Board of Education (SBOE) are unusually important because they are also adopted for use in classrooms across the country. Whatever Texas adopts, students across the United States get. In 2014, a coalition of unpaid Texas citizens who called themselves “Truth In Texas Textbooks,” presented the SBOE with a report containing 469 pages of factual errors, “imbalanced presentation of materials, omission of information, and opinions disguised as facts,” found in three world history and geography textbooks that were being considered for adoption that November. And who can forget the 2015 textbook fiasco, when the Texas Board of Education refused to allow professors to review and fact-check textbooks that were to be implemented in Texas curricula that year. Historians and other academics protested because non-experts were writing and reviewing history textbooks.

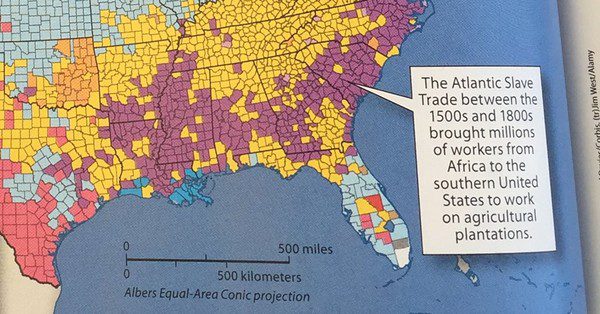

But that was not the only contentious issue surrounding textbooks in Texas last year. Mrs. Roni Dean-Burren split open a Pandora’s box of controversies when she posted a picture on Facebook of her teenage son’s textbook which explicitly portrayed slaves as immigrant workers. The Texas State Board of Education had adopted the textbook, published by McGraw Hill, a few years ago and sold about 140,000 in Texas and other states. McGraw Hill was quick to respond and quench the controversy. They immediately acknowledged that they had made “a mistake” and rapidly agreed to do their “utmost to fix it.”

This year’s controversy has had a different outcome. Unlike McGraw Hill, Jaime Riddle and Valarie Angle, the authors of the Mexican American Heritage textbook and its publisher, Momentum Instruction, LLC, have yet to apologize for a widely criticized textbook. Beyond an unwillingness to acknowledge the large number of problems in their textbook, they have failed to respond to questions and comments from historians and experts challenging their work. The Mexican American Heritage textbook has more than 800 factual errors, errors of omission, and misleading representations of Mexican American history and culture.

In addition to factual errors, the book is riddled with what several historians have deemed “ethnic hostility” — clearly racist remarks, blatantly condescending portrayals of Mexican Americans and their historical roles, and a large number of specific instances where the authors’ opinions straightforwardly belittle Mexican-American history, heritage, and people of Mexican descent and their accomplishments and contributions. The authors and the publisher have refused to work with experts to fix the errors and have yet to demonstrate any intent to withdraw the book from consideration for adoption by the State Board of Education in hearings scheduled for November 15 and 18, 2016. The final decision pertaining to the adoption or rejection of the textbook is set to be made on November 18, 2016.

A textbook with an extensive number of errors, with clearly racist and condescending content does not belong in any classroom. Textbooks are meant to educate and empower our future generations through an emphasis on factual history and on understanding the heritage and identity of all the peoples of the country, but the Mexican American Heritage textbook is set to do just the opposite. Its content erases Mexican American history and culture and it presents historical information in manner that misinforms, rather than educates.

For instance, a passage in the book claims that “in 1822, Moses Austin obtained the first charter to start an American colony in Texas.” As most historians know, what Austin received was not a charter, but an offer for a land grant where up to 300 colonists could move and settle in Texas, then Mexican territory, with the stipulation that they swear allegiance to Mexico and become Mexican citizens. Also, expert historians made sure to note that Moses Austin died in 1821, so by 1822, the date provided in the textbook, Austin was in fact no longer alive and could not have obtained what the authors claimed was the first charter to colonize Texas.

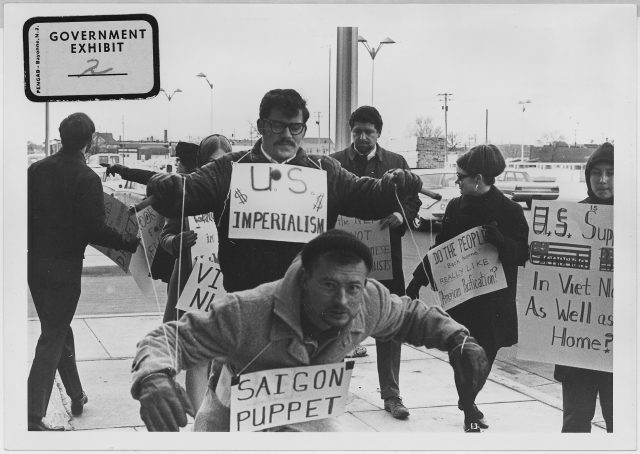

Last month The Guardian reported that the passages in the textbook portray Mexican Americans as “anti-education and anti-English” and depict “true Mexican identity” as being inherently in rebellion against the establishment. They write that “High School and college youth may refuse to attend class, speak English or learn certain subjects because they perceive injustice in the school system,” and claiming Mexican American prosperity is hindered by their own identity. In addition to reports in the media, the Ad Hoc Committee, consisting of a group of scholars who took the initiative to read and review the textbook last spring, have highlighted some of the most disturbing errors. In chapter 3, for example, the authors wrote that “most Mexicans weren’t literate, they could not own land, and had been given the message that they should be subdued rather than lifted up. How would they invent a system from nothing that depended on participating in political and economic life?”[1] They portray Mexican Americans as having an all-encompassing cultural attitude of laziness that makes them put off important things for “mañana,” because, according to the textbook, they “have not been reared to put in a full day’s work so vigorously.”

Contrary to those portrayals, Mexican Americans and Mexican American scholars, historians and other professionals have begun the rigorous undertaking of meticulously reviewing the textbook by tabulating historical inaccuracies, listing factual errors, and conducting extensive and in depth analysis of the historical content of the textbook. The Mexican American scholars and the community were quick to organize in Austin and across Texas, and have managed to coordinate with other scholars, and historians across the country to write a strong case against the Mexican American Heritage textbook, so that it is not adopted by the Texas State Board of Education in the November hearings. The Ad Hoc Committee presented its report this past summer to the Texas State Board of Education’s Representative, Ruben Cortez, Jr., to explain why the proposed textbook was inadequate, how it failed to meet basic standards and guiding principles in the history profession. They provided an extensive list of suggested revisions to the publisher, suggestions that today, at one week until the hearing, have gone vastly unheeded.

Here at UT Austin, the University of Texas Textbook Review Committee has six members working under the guidance of Dr. Emilio Zamora, of the UT Austin History Department, to produce a complete annotated list of factual errors, omissions, and misrepresentations, and also a list of suggested revisions. The committee’s goal is to serve historians and experts such as Dr. Zamora to prepare a written response based on their findings and historical evidence, to present to the Texas State Board of Education on November 15, and for that response to help prevent the Mexican American Heritage textbook from being adopted.

Despite the documented factual errors and wide criticism of the textbook, the hearing is not going to be an easy one. Conservative politicians have been supporting adoption of the textbook. For example, David Bradley, the Republican state representative for Southeast Texas on the Texas Board of Education, said that he had originally voted against the call for textbooks because he considers Mexican-American studies to be discriminatory against Americans of other ethnic backgrounds. He now plans to vote to adopt the book, because he is “going to give them what they asked for.” Bradley added “they wanted a course, and they wanted special treatment, and we had publisher step up.” He is intent on casting his vote for the adoption of this textbook.

Criticism of the textbook has come from historians across the nation, professional organizations, and activists’ platforms, including American Historical Association. In September, the AHA wrote a letter of concern to the Texas State Board of Education regarding the textbook because, they wrote, “the textbook does not adequately reflect the scholarship of historians who have worked in the field of Mexican American history, or measure up to the broad standards of history as a discipline.” The American Historical Association urged the Texas Board of Education “reject the use of this textbook as an option for institutions within the purview of the board’s adoption policies.”

We hope that more allies come to our support, and that many scholars, historians, educators, and students show up at the William B. Travis Building at the State Capitol for the hearings on November 15. It is imperative that textbooks such as The Mexican American Heritage do not get adopted. A textbook on Mexican Americans or Mexican American history or any other history that is filled with errors and racist allegations should not be used to educate our children, not now, not ever.

[1]District 2 Ad Hoc Committee Report on Proposed Social Studies Special Topic Textbook: Mexican American Heritage, presented to Ruben Cortez, Jr., State Board of Education Representative, September 6, 2016.

Board of Education agendas and information for the November 15th-18th meetings can be found here.

A map indicating the building location can be found here.

You can find out who your SBOE representative is here, and can contact members of the SBOE here.

You may also like:

Chris Babits offers Another Perspective on the Texas Textbook Controversy.

Christopher Rose recounts his experience testifying before the SBOE in this blog post.

NEP contributors relate what happens When a Government Tells Historians How to Write and How to Teach.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.